This ABC mini-series was first broadcast in February, 1979, 18 months after Elvis Presley had died. Albert Goldman’s misanthropic biography was still two years away, but some of the King’s less salubrious habits had been detailed in Elvis: What Happened, published by members of his entourage months before his demise. The image had cracked, but it hadn’t yet been obliterated. And nor had it turned into any of the other peculiar accompaniments of the posthumous Presley myth, where the brilliance of Elvis is hidden by commerce, mock-religion, or deliberate stupidity. Kurt Russell’s performance was rightly praised, earning him an Emmy nomination that set him up for future collaborations with John Carpenter (notably Escape From New York and The Thing). Russell’s ability to play Elvis as a real man shouldn’t be underestimated – after all, Presley spent much of his own movie career playing a cartoon of himself. (The casting of Kurt’s father, Bing, as Presley’s father, Vernon adds a further level of verisimilitude). Carpenter talks in the short promo film, Elvis: Bringing A Legend To Life, about how his film was a sincere attempt to tell the story of a man who became larger than life. He concedes that much of the material will be familiar to us, but suggests that some will not. I’d guess that the foregrounding of Elvis’ relationship with his mother, Gladys, was news in 1979, though it falls far short of later interpretations, which extended – implausibly – to incest. Carpenter’s Elvis is also in the habit of confiding with his dead twin, Jesse. He does this first as a child at his brother’s graveside. This sets up a key scene – a conversation with his shadow on the wall of the Hilton International hotel in Las Vegas. “I got it all, man,” Elvis says, as if addressing Jesse. “I oughta be the happiest person in the world, but I still feel there’s something missing.” He reaches out to touch his own silhouette. “Like somewhere deep inside, there’s an empty place. What’s it gonna take, man? What’s it gonna take to fill that up?” It’s not quite “Alas, poor Yorick,” but the sense of hurt is poignantly expressed. So, this is the Elvis who took up permanent residence on Lonely Street, confused and disabled by fame. There is no mention of drugs, apart from a couple of moments of irregular behaviour and odd lapses into paranoia. We see Elvis screening Rebel Without A Cause on the wall of his den, mouthing James Dean’s lines: “Boy, if I had one day, when I didn’t have to be all confused, if I felt that I belonged someplace…” And that, really, is the point. Elvis was an outsider. No-one had lived a life like his before, and the crude diagnosis is that he wasn’t able to cope with it. Happily, Carpenter omits the final chapter in Elvis’ life, stopping the action in 1969, with Presley’s triumphant return to the stage. Arguably, Russell played Fat Elvis in Tarantino’s Death Proof. Here, he delivers a version of Elvis from the time before the myth took on a life of its own. Trapped between a shy boy’s sneer and a showman’s smile, he strides into the Vegas lights, fearing, half hoping, his life will be ended by an assassin’s bullet. EXTRAS: Featurette, clips from American Bandstand, commentary by Ronnie McDowell and Presley’s cousin, Edie Hand, and gallery. Alastair McKay

This ABC mini-series was first broadcast in February, 1979, 18 months after Elvis Presley had died. Albert Goldman’s misanthropic biography was still two years away, but some of the King’s less salubrious habits had been detailed in Elvis: What Happened, published by members of his entourage months before his demise.

The image had cracked, but it hadn’t yet been obliterated. And nor had it turned into any of the other peculiar accompaniments of the posthumous Presley myth, where the brilliance of Elvis is hidden by commerce, mock-religion, or deliberate stupidity.

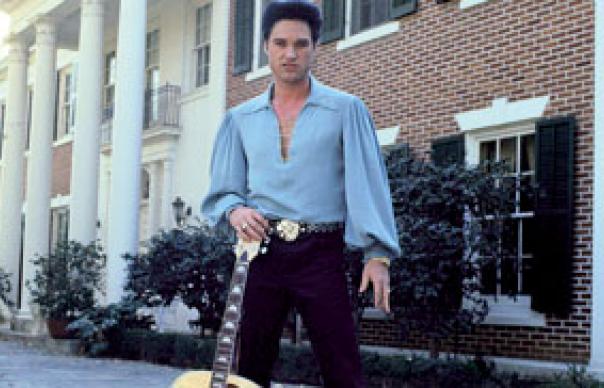

Kurt Russell’s performance was rightly praised, earning him an Emmy nomination that set him up for future collaborations with John Carpenter (notably Escape From New York and The Thing). Russell’s ability to play Elvis as a real man shouldn’t be underestimated – after all, Presley spent much of his own movie career playing a cartoon of himself. (The casting of Kurt’s father, Bing, as Presley’s father, Vernon adds a further level of verisimilitude).

Carpenter talks in the short promo film, Elvis: Bringing A Legend To Life, about how his film was a sincere attempt to tell the story of a man who became larger than life. He concedes that much of the material will be familiar to us, but suggests that some will not. I’d guess that the foregrounding of Elvis’ relationship with his mother, Gladys, was news in 1979, though it falls far short of later interpretations, which extended – implausibly – to incest.

Carpenter’s Elvis is also in the habit of confiding with his dead twin, Jesse. He does this first as a child at his brother’s graveside. This sets up a key scene – a conversation with his shadow on the wall of the Hilton International hotel in Las Vegas. “I got it all, man,” Elvis says, as if addressing Jesse. “I oughta be the happiest person in the world, but I still feel there’s something missing.” He reaches out to touch his own silhouette. “Like somewhere deep inside, there’s an empty place. What’s it gonna take, man? What’s it gonna take to fill that up?” It’s not quite “Alas, poor Yorick,” but the sense of hurt is poignantly expressed.

So, this is the Elvis who took up permanent residence on Lonely Street, confused and disabled by fame. There is no mention of drugs, apart from a couple of moments of irregular behaviour and odd lapses into paranoia. We see Elvis screening Rebel Without A Cause on the wall of his den, mouthing James Dean’s lines: “Boy, if I had one day, when I didn’t have to be all confused, if I felt that I belonged someplace…” And that, really, is the point. Elvis was an outsider. No-one had lived a life like his before, and the crude diagnosis is that he wasn’t able to cope with it. Happily, Carpenter omits the final chapter in Elvis’ life, stopping the action in 1969, with Presley’s triumphant return to the stage.

Arguably, Russell played Fat Elvis in Tarantino’s Death Proof. Here, he delivers a version of Elvis from the time before the myth took on a life of its own. Trapped between a shy boy’s sneer and a showman’s smile, he strides into the Vegas lights, fearing, half hoping, his life will be ended by an assassin’s bullet.

EXTRAS: Featurette, clips from American Bandstand, commentary by Ronnie McDowell and Presley’s cousin, Edie Hand, and gallery.

Alastair McKay