The Velvet Underground begins with a quote from French poet Charles Baudelaire: “Music fathoms the sky.” It doesn’t explain much about the two hours that follow, but it does make clear that director Todd Haynes is looking at the band from the perspective of a fellow artist rather than an archivist.

- ORDER NOW: The August 2021 issue of Uncut

The director of I’m Not There is trying to understand what the Velvets achieved rather than laying out the facts of where and when they did it. Which is just as well, because the Velvets story is famously slippery. After all, this is a band whose career weathered numerous twists and challenges that could have killed off less stubborn groups: when John Cale was sacked, when Sterling Morrison absconded, when Lou Reed quit and when Maureen Tucker eventually left Doug Yule to shop the band around in name-only form to British students on a 1973 college tour.

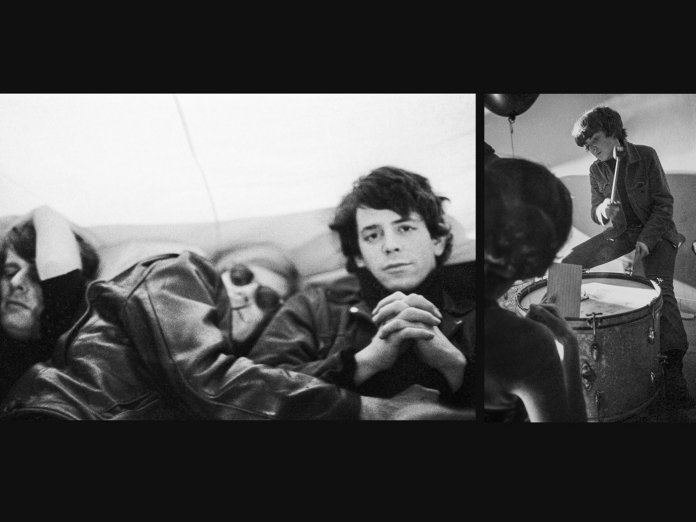

Haynes opens his film on familiar ground. We are given the contrasting back stories of Reed (the troubled Brooklyn teenage rock’n’roller who thought he’d score a Billboard hit with a novelty dance tune called “The Ostrich”) and Cale (the classically trained Welshman whose head was turned by the avant garde movement). Around them, the band of unlikely bedfellows quickly coalesces – Tucker, then Morrison, then Nico, whose introduction by manager Andy Warhol turned out to be a stroke of genius. Just as Warhol polarised pop culture, the Velvets and their entourage seemed to set themselves up in direct contrast to the prevailing late ‘60s vibes. As the Aquarian age reached its peak, the band’s choice of black clothes and shades sent a clear message to the love generation. “Burn your bra?” sneers Mary Woronov, one of Warhol’s Superstars. “What the fuck is wrong with you?”

The narrative is provided by eyewitness interviews. Aside from surviving band members Cale, Tucker and Yule (Reed and Morrison’s voices also feature), Haynes rounds up friends, family, fans and fellow travellers, including avant-garde film archivist Jonas Mekas, Reed’s sister Merrill, composer La Monte Young and Jonathan Richman – who says he must have seen the band “60 or 70 times”.

Haynes’ immerses us in some stunning archive material – including Warhol’s studied screentests of the band’s blank, bored faces, rehearsal footage, poetry readings, recordings of conversations. He handles this material like an underground movie from a 1960s art lab, frequently using split screen, lens flare, and sprocket holes – just like the movies of Jack Smith, Kenneth Anger and Bruce Conner, whose work he samples. But there’s a strange paradox here. After claiming solidarity with the outside artists of his time – he namechecks writers Hubert Selby Jr, William Burroughs and John Rechy – Reed seemingly develops issues with his band becoming too out there, firing Warhol first, then Cale and pursuing a softer, more intimate sound. Post-Cale, Reed will try to crack California and – a far worst crime – let the band appear in daylight wearing floral shirts (in some ways, the film could be construed as a Joker-style Lou Reed origins story).

Whatever, the end was clearly in sight. Reed himself explains, the secret of the band’s music was its simplicity: they never added, only subtracted and wouldn’t record anything they couldn’t perform live. The same, rather sadly, is true of the band themselves – which ended in a series of subtractions until, just like that, there were none. It’s to Haynes’s credit that he doesn’t try to romanticise their failure (Tucker says she thought Verve only signed them “to keep us off the streets”), but instead try to put the viewer into their heads, as if hearing their music for the first time. It’s an audacious move – but, perhaps unsurprisingly for a filmmaker operating on Haynes’ level, it works.

The Velvet Underground screens Out of Competition at this year’s 74th Cannes Film Festival; it will be shown on Apple TV+ later this year