It’s a small miracle this film exists. In October 2018, a fire destroyed the Woodstock home of folk guitarist Peter Walker and with it the entire archive of his old friend Karen Dalton – her journals, handwritten lyrics, poetry and artwork. The loss is incalculable, but fortunately, just months before, he’d had everything digitised, allowing directors Richard Peete and Robert Yapkowitz to draw from these artifacts and paint the clearest picture yet of this mysterious and troubled – yet oddly influential – artist.

A free spirit from Oklahoma who had two kids and two ex-husbands by the time she turned 20, Dalton left the Midwest and arrived in New York City at the start of the folk revival. She stood out thanks to her fluid picking style and especially her stunning voice: in timbre it recalls Billie Holiday, but in phrasing and cadence it suggests no-one other than Dalton. The black-and-white footage of her early Greenwich Village performances is a highlight in the film, showing how she rearranged old, familar songs to sound fresh. Eschewing the populism associated with folk music at the time, Dalton sang everything as though it held some personal confession unique to her life. Her peers were awed, especially Bob Dylan (who thought she was the female Woody Guthrie).

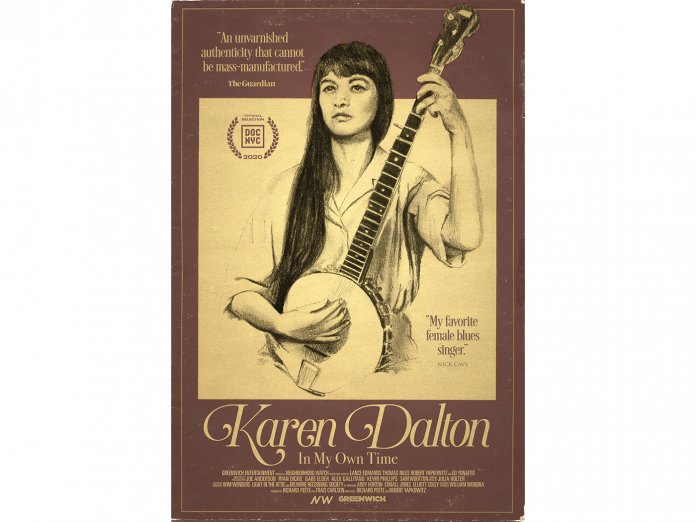

Dalton was ambivalent about a career in music. On one hand, she wanted the attention and affirmation, not to mention the financial security, and she envied the success of her Village peers. On the other hand, she was unwilling to pursue an audience or make any kind of concession to the industry. She didn’t release her debut, It’s So Hard To Tell Who’s Going To Love You Best, until 1969, long after folk had been thoroughly revived and mutated into folk-rock. Her follow-up, 1971’s In My Own Time, updated her sound with a small country band, but she felt it was impersonal and unrepresentative. (It’s not!) A thankless gig opening for Santana effectively ended her career. “The joy of it escaped her,” recalls Hunt Middleton, her boyfriend during that time.

Dalton had always been a casual drug user, but she quickly graduated to harder drugs in the 1970s and 1980s, leaving her homeless and forgotten. She died of Aids in 1993, with Walker caring for her in her final days. To its credit, the documentary offers no personal redemption, no deathbed revelation, nothing to suggest her story is anything but a tragedy. In fact, it might undersell the magnitude of her critical reassessment in the 2000s, when a series of reissues introduced her to a new generation of artists (including Angel Olsen, who reads from her journals). She emerges with all of her contradictions intact: confident in herself as an artist, relatably conflicted as a human being.