Florian Fricke was of the generation of West German musicians involved in the movement that would become known internationally as Krautrock. Yet the music he made in his group Popol Vuh between the years 1970 and his death in 2001 feels somewhat apart. Groups like Can, Faust and Neu! were making mu...

Florian Fricke was of the generation of West German musicians involved in the movement that would become known internationally as Krautrock. Yet the music he made in his group Popol Vuh between the years 1970 and his death in 2001 feels somewhat apart.

Groups like Can, Faust and Neu! were making music for a modern Germany, exploring new techniques, technologies, and philosophies. In some ways Frickewas a modernist too. He was amongst the first Germans to own a Moog synthesizer, which powered Popol Vuh’s 1970 debut album Affenstunde, as well as the soundtrack he made for his friend Werner Herzog’s feature film about conquistadors searching for the mythical Inca city of El Dorado, Aguirre, The Wrath Of God. But Fricke would soon tire of the synthesizer, and albums from 1972’s Hosianna Mantra on would focus on a spiritual, devotional music, using piano and more exotic instruments such as the oboe, konga, and tamboura. The guiding principle was not progress, but peace – or as Fricke put it: “Popol Vuh is a mass for the heart. It is music for Love. Das ist alles.”

This new collection, sanctioned by Fricke’s family, draws from two sources. The first disc collects eight solo piano recordings, a mix of unheard improvisations and sketches of more developed Popol Vuh pieces (three “Spirit Of Peace” pieces are test runs for the title track of the 1985 album of the same name; others appear to be prototypes of tracks from 1972’s Hosianna Mantra). Fricke’s playing is minimal but purposeful. As a youth, he practised Bach and Schubert, and surely could have been a concert pianist had the mood taken him. Indeed, he released an album of Mozart pieces in 1991.

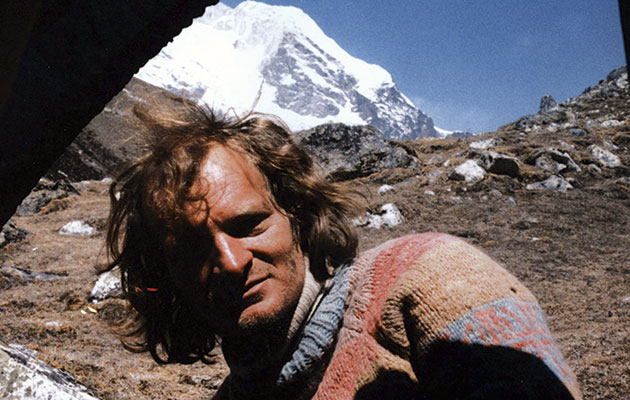

Perhaps more interesting, though, is the DVD and accompanying soundtrack disc, which contain the long-lost Kailash: A Pilgrimage To The Throne Of The Gods. A 53-minute film made by Fricke with Popol Vuh member Frank Fielder operating the camera, it’s a sort of travelogue charting the pair’s journey up the mountain of the same name, a 21,000-foot peak in west Tibet considered holy by Hindus and Buddhists alike. Its slow pans across remote encampments, wandering yak-herders, and pilgrims prostrating themselves as they make their ascent feel almost Herzogian in their craggy beauty. But the serenity of Fricke’s vision shines through, in large part thanks to the music. “Buddha’s Footprint” and “Valley Of The Gods” are billowing synthesizer pieces with subtle but effective ethnic flourishes that feel just one sheer face from the divine.