The Zappa Motherlode: 12 albums reissued this month and 48 more by the end of the year... “He established a musical category of his own – ‘Zappa’,” his former keyboardist George Duke once remarked. As a category, ‘Zappa’ was a mélange of juxtapositions, or perhaps a collage of mosaics, that included wacky surf tunes, modern jazz, comedy skits and musique concrète – and that was just the first five minutes of Lumpy Gravy. ‘Zappa’ was serious-yet-witty music played on harpsichords and xylophones, with woodwinds and operatic vocals, wah-wah solos and manic time signatures. Then there were the gags: scathing, political, puerile, like Armando Ianucci in a brainstorming meeting with Finbarr Saunders. Given the enormous dimensions of Zappa’s output, his back catalogue can seem daunting. Where do you start? Where do you stop? In the mid-’90s, the American reissue label Rykodisc paid $20 million for the rights to 53 Zappa CDs and released them all in one simultaneous splurge. It was a heroic gesture of Zappaesque nonconformism, but it did little to make sense of his towering oeuvre. Universal’s more nuanced Zappa blitz – 12 albums this month, to be followed by another 48 before the end of November – is the result of a distribution deal between the Zappa Family Trust (headed by Frank’s widow Gail) and the world’s biggest multinational music corporation. They make an unexpectedly good team. Hard-to-please Zappa forums have expressed online delight at the ZFT/Universal remasters (particularly Hot Rats, Absolutely Free and Chunga’s Revenge), which not only sound fantastic but also get tantalisingly close to the original 1967–70 vinyl versions. Freak Out! (1966; 9/10) and Absolutely Free (1967; 8/10) were extraordinary early works. They were credited not to Zappa but to The Mothers Of Invention, a weird-beard conglomerate who could play everything from Stravinsky to greasy R&B. Freak Out!, vicious in its condemnation of LBJ’s America, begins with a sequence of deceptively accessible songs but becomes more deranged as its 60 minutes unfold. The Mothers start banging on drumkits, conversing in high-pitched Latino gibberish and fixating on the words “creamcheese” and “America is wonderful”. On Absolutely Free, the comedy gets even darker. The President is brain-dead and the complacent middle-aged businessmen have sexual designs on their teenage daughters. But Zappa’s eye, as ever, roves towards the surreal. He professes a love for vegetables. He enthuses about prunes and their amazing relationship with cheese. “This is the exciting part,” he announces as the song gathers pace. “This is like The Supremes... see the way it builds up?” The Mothers retort by singing, “Baby prune, my baby prune” like some awful, cynical, Motown-hating lounge band. We’re Only In It For The Money (1968; 8/10) is, if anything, even more vituperative and magnificent. A commentary on the Summer Of Love, which the LSD-shunning Zappa viewed as a shallow parade of witless hippies, We’re Only... is ruthlessly satirical, and breathtakingly topical, but it’s also oddly poignant with its helium-voiced psychedelic losers (“I hope she sees me dancing and twirling”) and its melodically sumptuous mini-suites. It’s an album that takes the almighty piss out of Sgt. Pepper and yet, strangely, begs to be heard alongside it and judged as no less historic and important. Almost as satirical, if not as panoramic, is Cruising With Ruben & The Jets [7/10], a homage to long-forgotten doowop groups, in which Zappa, a massive doowop fan himself, manages to come across as endearing and sincere even when the comedy is exquisitely sardonic. Lumpy Gravy (1967; 7/10), a collage-style concept album, contains some of his most avant-garde music as well as some of his most bizarre encounters with his fellow Mothers. At one point a lengthy discussion of the word “dark” is held by three people who sound like they’re trapped inside a cardboard box. It’s a puzzling hiatus amid the insane music. This is a Zappa that you can easily imagine sitting in his studio, surrounded by empty cigarette cartons and cups of coffee, adding impatiently to his immense pile of productivity. Hot Rats (1969; 9/10) is the ideal way-in for Zappa newcomers. An instantly likeable jazz-rock album, warm and uplifting, it’s primarily instrumental except for a vocal cameo by Captain Beefheart. Hot Rats has a way of sounding rigidly structured and at the same time utterly free. It isn’t really jazz, though it relies heavily on solos, but it’s not quite rock because the solos are so jazzy. It’s a special record. Uncle Meat (1969; 7/10), the nearest thing to Hot Rats in the early Zappa canon, has more of his jaw-dropping woodwind and keyboard parts, but is not as easy to get into – it’s a double album, for a start – even if his outlandish harmonic structures do eventually, after many listens, worm themselves into the brain and become addictive. The early ’70s albums are where you’ll find mock-German accents, jazz violin workouts, skronk jazz and send-ups of Pete Townshend’s rock operas (“Billy The Mountain”). Unfortunately, the live outings (Fillmore East – June 1971, Just Another Band From LA; both 6/10), with their groupie-obsessed shenanigans and the acquired-taste hysteria of Flo and Eddie, are a bit like watching an ageing double act in panto and trying to remember why they were funny in the first place. Zappa’s singular humour, God bless it, looms large over these albums. It’s possible he mightn’t have approved of certain ZFT policies in this reissue programme, such as the decision to overrule some of his old remixes, but he could hardly accuse the campaign of lacking bullishness. “Long may his baton wave,” Gail declares in her press statement. “We are so ready to go.” The curious thing is, only a third of the catalogue has been newly remastered. Five of the 12 albums (Freak Out!, We’re Only In It For The Money, Lumpy Gravy, Cruising With Ruben & The Jets and Uncle Meat) are straight reruns of the CDs released by Rykodisc in 1995. Others, like Hot Rats and Absolutely Free, are stunningly different. What would Zappa think of it all? Old versions or new? Maybe, as he leaned back into his solo on “Willie The Pimp”, he’d rather we concentrated on the music rather than the audio signal path. David Cavanagh Q&A DON PRESTON (Mothers Of Invention keyboardist, 1966-69; 1971) What was it like working with Zappa? That’s like asking ‘how did it feel when your mother died right in front of you?’ Ha ha! Well, you know, we just tried to make good music and have fun. I personally was trying to incorporate things I was interested in – like experimental music and electronic sounds – into The Mothers. That’s why Zappa hired me. Zappa was a self-taught musician. How significant was that? His music doesn’t fit into any category. His main interests were classical, jazz, doowop and rock’n’roll. He’d listened to the contemporary composers – notably Varèse, Stravinsky and Bartók – and he sometimes wrote basslines in 11/8 and melodies in 12/8, which gave The Mothers a very distinctive sound. But he’d also learned a lot about rock’n’roll. You can’t play "Louie Louie" without hearing it. Once you’ve heard it, it’s simple – but it’s not simple until you’ve heard it. And ‘Louie Louie’, of course, became the basis for "Plastic People" and "Son Of Suzy Creamcheese" on Absolutely Free. Is that you playing “Louie Louie” on the Albert Hall pipe organ on Uncle Meat? That’s me. It was the second largest organ in the world at the time. Later, we got a letter from a guy who’d been to that concert. He said, "I’d just arrived in England and I was wondering whether to stay or go back home to America. Then Don Preston climbed up the seats and played 'Louie Louie' on the pipe organ, and that’s when I knew I had to stay in England." Signed Terry Gilliam. How were the early Mothers albums made? Things worked different ways. When we recorded Absolutely Free, we only had a 4-track machine and three people in the band couldn’t read music. So Zappa would record eight bars of, say, "Brown Shoes Don’t Make It" 25 times. Then we’d go to the next eight bars – and we’d do that 25 times. And so on, through the entire piece. Afterwards Zappa would select the best take of each eight bars and piece them all together. He was a compulsive editor. One of the problems of being in The Mothers was that once you’d learned a piece, it would change the next week. Sometimes radically. Sometimes you wouldn’t even recognise it. Zappa was constantly creating. At rehearsals, he’d often be recreating a song he’d already written. It was part of the compulsive editing process. We’re Only In It For The Money is a satire of the San Francisco psychedelic scene. Did Zappa really hate those bands? “No, I don’t think he hated them. But he had a sarcastic view of almost everything. That was his nature. That was his kind of comedy. When he sat down to write lyrics, I don’t think he thought, ‘Now I’m going to point out all the ridiculous things about the hippie scene.’ But he was making a serious point that the hippies were wearing costumes and forming regiments like everybody they were claiming to be free from.” Are you the band-member on Uncle Meat who protests to Zappa that “this fucking band is starving”? No, that’s Jimmy Carl Black [drums]. We’d been working in New York for months and we hadn’t got paid from our shows at the Garrick Theatre. Jimmy was complaining about that. As musicians, yes, I would say we probably got ripped off a few times, but we were able to make enough money to stay alive. And I’m on tour right now, playing Frank Zappa’s music with The Grandmothers, and it sounds great. You have to have phenomenal musicians and we do. Not everyone can play this music. INTERVIEW: DAVID CAVANAGH

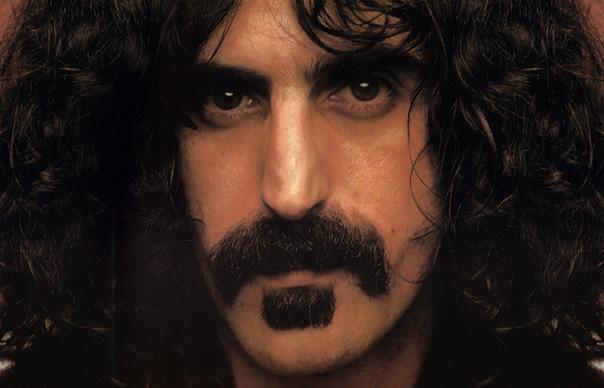

The Zappa Motherlode: 12 albums reissued this month and 48 more by the end of the year…

“He established a musical category of his own – ‘Zappa’,” his former keyboardist George Duke once remarked. As a category, ‘Zappa’ was a mélange of juxtapositions, or perhaps a collage of mosaics, that included wacky surf tunes, modern jazz, comedy skits and musique concrète – and that was just the first five minutes of Lumpy Gravy. ‘Zappa’ was serious-yet-witty music played on harpsichords and xylophones, with woodwinds and operatic vocals, wah-wah solos and manic time signatures. Then there were the gags: scathing, political, puerile, like Armando Ianucci in a brainstorming meeting with Finbarr Saunders.

Given the enormous dimensions of Zappa’s output, his back catalogue can seem daunting. Where do you start? Where do you stop? In the mid-’90s, the American reissue label Rykodisc paid $20 million for the rights to 53 Zappa CDs and released them all in one simultaneous splurge. It was a heroic gesture of Zappaesque nonconformism, but it did little to make sense of his towering oeuvre. Universal’s more nuanced Zappa blitz – 12 albums this month, to be followed by another 48 before the end of November – is the result of a distribution deal between the Zappa Family Trust (headed by Frank’s widow Gail) and the world’s biggest multinational music corporation. They make an unexpectedly good team. Hard-to-please Zappa forums have expressed online delight at the ZFT/Universal remasters (particularly Hot Rats, Absolutely Free and Chunga’s Revenge), which not only sound fantastic but also get tantalisingly close to the original 1967–70 vinyl versions.

Freak Out! (1966; 9/10) and Absolutely Free (1967; 8/10) were extraordinary early works. They were credited not to Zappa but to The Mothers Of Invention, a weird-beard conglomerate who could play everything from Stravinsky to greasy R&B. Freak Out!, vicious in its condemnation of LBJ’s America, begins with a sequence of deceptively accessible songs but becomes more deranged as its 60 minutes unfold. The Mothers start banging on drumkits, conversing in high-pitched Latino gibberish and fixating on the words “creamcheese” and “America is wonderful”. On Absolutely Free, the comedy gets even darker. The President is brain-dead and the complacent middle-aged businessmen have sexual designs on their teenage daughters. But Zappa’s eye, as ever, roves towards the surreal. He professes a love for vegetables. He enthuses about prunes and their amazing relationship with cheese. “This is the exciting part,” he announces as the song gathers pace. “This is like The Supremes… see the way it builds up?” The Mothers retort by singing, “Baby prune, my baby prune” like some awful, cynical, Motown-hating lounge band.

We’re Only In It For The Money (1968; 8/10) is, if anything, even more vituperative and magnificent. A commentary on the Summer Of Love, which the LSD-shunning Zappa viewed as a shallow parade of witless hippies, We’re Only… is ruthlessly satirical, and breathtakingly topical, but it’s also oddly poignant with its helium-voiced psychedelic losers (“I hope she sees me dancing and twirling”) and its melodically sumptuous mini-suites. It’s an album that takes the almighty piss out of Sgt. Pepper and yet, strangely, begs to be heard alongside it and judged as no less historic and important. Almost as satirical, if not as panoramic, is Cruising With Ruben & The Jets [7/10], a homage to long-forgotten doowop groups, in which Zappa, a massive doowop fan himself, manages to come across as endearing and sincere even when the comedy is exquisitely sardonic. Lumpy Gravy (1967; 7/10), a collage-style concept album, contains some of his most avant-garde music as well as some of his most bizarre encounters with his fellow Mothers. At one point a lengthy discussion of the word “dark” is held by three people who sound like they’re trapped inside a cardboard box. It’s a puzzling hiatus amid the insane music. This is a Zappa that you can easily imagine sitting in his studio, surrounded by empty cigarette cartons and cups of coffee, adding impatiently to his immense pile of productivity.

Hot Rats (1969; 9/10) is the ideal way-in for Zappa newcomers. An instantly likeable jazz-rock album, warm and uplifting, it’s primarily instrumental except for a vocal cameo by Captain Beefheart. Hot Rats has a way of sounding rigidly structured and at the same time utterly free. It isn’t really jazz, though it relies heavily on solos, but it’s not quite rock because the solos are so jazzy. It’s a special record. Uncle Meat (1969; 7/10), the nearest thing to Hot Rats in the early Zappa canon, has more of his jaw-dropping woodwind and keyboard parts, but is not as easy to get into – it’s a double album, for a start – even if his outlandish harmonic structures do eventually, after many listens, worm themselves into the brain and become addictive.

The early ’70s albums are where you’ll find mock-German accents, jazz violin workouts, skronk jazz and send-ups of Pete Townshend’s rock operas (“Billy The Mountain”). Unfortunately, the live outings (Fillmore East – June 1971, Just Another Band From LA; both 6/10), with their groupie-obsessed shenanigans and the acquired-taste hysteria of Flo and Eddie, are a bit like watching an ageing double act in panto and trying to remember why they were funny in the first place. Zappa’s singular humour, God bless it, looms large over these albums. It’s possible he mightn’t have approved of certain ZFT policies in this reissue programme, such as the decision to overrule some of his old remixes, but he could hardly accuse the campaign of lacking bullishness. “Long may his baton wave,” Gail declares in her press statement. “We are so ready to go.” The curious thing is, only a third of the catalogue has been newly remastered. Five of the 12 albums (Freak Out!, We’re Only In It For The Money, Lumpy Gravy, Cruising With Ruben & The Jets and Uncle Meat) are straight reruns of the CDs released by Rykodisc in 1995. Others, like Hot Rats and Absolutely Free, are stunningly different. What would Zappa think of it all? Old versions or new? Maybe, as he leaned back into his solo on “Willie The Pimp”, he’d rather we concentrated on the music rather than the audio signal path.

David Cavanagh

Q&A

DON PRESTON (Mothers Of Invention keyboardist, 1966-69; 1971)

What was it like working with Zappa?

That’s like asking ‘how did it feel when your mother died right in front of you?’ Ha ha! Well, you know, we just tried to make good music and have fun. I personally was trying to incorporate things I was interested in – like experimental music and electronic sounds – into The Mothers. That’s why Zappa hired me.

Zappa was a self-taught musician. How significant was that?

His music doesn’t fit into any category. His main interests were classical, jazz, doowop and rock’n’roll. He’d listened to the contemporary composers – notably Varèse, Stravinsky and Bartók – and he sometimes wrote basslines in 11/8 and melodies in 12/8, which gave The Mothers a very distinctive sound. But he’d also learned a lot about rock’n’roll. You can’t play “Louie Louie” without hearing it. Once you’ve heard it, it’s simple – but it’s not simple until you’ve heard it. And ‘Louie Louie’, of course, became the basis for “Plastic People” and “Son Of Suzy Creamcheese” on Absolutely Free.

Is that you playing “Louie Louie” on the Albert Hall pipe organ on Uncle Meat?

That’s me. It was the second largest organ in the world at the time. Later, we got a letter from a guy who’d been to that concert. He said, “I’d just arrived in England and I was wondering whether to stay or go back home to America. Then Don Preston climbed up the seats and played ‘Louie Louie’ on the pipe organ, and that’s when I knew I had to stay in England.” Signed Terry Gilliam.

How were the early Mothers albums made?

Things worked different ways. When we recorded Absolutely Free, we only had a 4-track machine and three people in the band couldn’t read music. So Zappa would record eight bars of, say, “Brown Shoes Don’t Make It” 25 times. Then we’d go to the next eight bars – and we’d do that 25 times. And so on, through the entire piece. Afterwards Zappa would select the best take of each eight bars and piece them all together. He was a compulsive editor. One of the problems of being in The Mothers was that once you’d learned a piece, it would change the next week. Sometimes radically. Sometimes you wouldn’t even recognise it. Zappa was constantly creating. At rehearsals, he’d often be recreating a song he’d already written. It was part of the compulsive editing process.

We’re Only In It For The Money is a satire of the San Francisco psychedelic scene. Did Zappa really hate those bands?

“No, I don’t think he hated them. But he had a sarcastic view of almost everything. That was his nature. That was his kind of comedy. When he sat down to write lyrics, I don’t think he thought, ‘Now I’m going to point out all the ridiculous things about the hippie scene.’ But he was making a serious point that the hippies were wearing costumes and forming regiments like everybody they were claiming to be free from.”

Are you the band-member on Uncle Meat who protests to Zappa that “this fucking band is starving”?

No, that’s Jimmy Carl Black [drums]. We’d been working in New York for months and we hadn’t got paid from our shows at the Garrick Theatre. Jimmy was complaining about that. As musicians, yes, I would say we probably got ripped off a few times, but we were able to make enough money to stay alive. And I’m on tour right now, playing Frank Zappa’s music with The Grandmothers, and it sounds great. You have to have phenomenal musicians and we do. Not everyone can play this music.

INTERVIEW: DAVID CAVANAGH