The quiet Beatle's escape attempts remastered... George Harrison wasn’t the first to attempt an escape from the Beatles’ gilded cage – that was an exasperated Ringo, during the making of the White Album – but he was the first to prepare for a different existence after the inevitable end of the collective dream. In 1968 he became the first to make an album, Wonderwall Music, under his own name. A year later he was the first to go on the road with a group of musicians other than his fellow Mop Tops, namely Delaney and Bonnie and their fashionable friends, including Eric Clapton and Leon Russell. With these gestures he had built a platform for a new life. Wonderwall Music is the first item in this new box set of digitally remastered studio albums from Harrison’s Apple period. Written for Joe Massot’s film, which starred the unlikely combination of Jane Birkin, Jack McGowran, Irene Handl and Richard Wattis, it is a treat from start to finish. With no previous experience of writing soundtracks, Harrison recorded the music in Bombay studio and London, edited the results with the use of a stopwatch while watching Massot’s unfinished footage. More than four and a half decades later the 18 tracks sound like an exploded diagram of a Beatles album, as viewed from Harrison’s off-centre perspective. Just about all the elements of the group’s overtly experimental period (1965-68) are there. Dreamy miniature ragas, featuring the ululations of the double-reed shenai (the opening “Microbes”, for example), give way to a pub knees-up gatecrashed by a Dixieland band (“Drilling a Home”), to the bones of early acid-rock songs (“Red Lady Too” and “Party Seacombe”), to a snatch of clippity-clop cowboy music called, of all things, “Cowboy Music”, and to a chant of “Om” accompanied by a harmonium. “Ski-ing” juxtaposes rock and raga, opening with an urgent guitar solo that sounds very much like Eric Clapton. “Dream Scene” is a collage of found sounds, anticipating Lennon’s “Revolution No 9”. If the Beatles’ collective sense of humour, a larky surrealism best preserved in their fan club Christmas flexidiscs, was largely inherited from the Goons, then the inspiration for Harrison’s Electronic Music in 1969 surely came from another BBC institution of their formative years: the Radiophonic Workshop. On this album - first released on the Zapple label, Apple’s short-lived experimental subsidiary - we witness the joy of a boy with a new toy as Harrison spends 44 minutes discovering the sounds to be coaxed from a Moog synthesiser. Apparently he had some outside help: Bernie Krause, a pioneer of the new instrument, later claimed that a passage on the second side of the original LP release was lifted straight from a lesson he gave Harrison in how to operate the device. With no pretensions to melody, harmony, pulse or any serious conceptual thinking, Electronic Music sounds like what you might get if you taped a contact microphone to the stomach of a digestively challenged robot: a lot of random rumbling, squeaking, hissing and groaning. A message appeared on the sleeve, credited to one Arthur Wax: “There are a lot of people around, making a lot of noise; here’s some more.” That still sums it up. After these two albums, All Things Must Pass reasserted Harrison’s status as a songwriter whose work had once earnt its place, albeit a lesser one, alongside that of Lennon and McCartney, whose initial solo efforts, with their reversion to rockabilly and skiffle primitivism, he instantly eclipsed. A lavishly packaged triple album, it benefited from the attention of Phil Spector, whose well known production techniques – more instruments, more echo -- served to disguise the whiny, monotonous tendency of Harrison’s voice, the preachiness of his lyrics and the inconsistent quality of his melodic gift. “My Sweet Lord” provided the worldwide hit and retains its surging power, as do “Beware of Darkness”, “What is Life” and “Awaiting on You All”. Nothing, however, can redeem the turgid instrumental jams – featuring Clapton, Billy Preston, Ginger Baker, Dave Mason and others – that made up the original third LP. Without Spector to enrich his sonic environment, Harrison’s subsequent albums lapsed into a drabness only sporadically relieved by something like his version of the Everly Brothers’ “Bye Bye Love”, from the widely panned Dark Horse, where he sought the kind of return to bare-bones rock and roll simplicity that Lennon had achieved with “Instant Karma”. A man so rich in material resource and spiritual support had allowed the concerns first expressed in “Taxman” and “Within You, Without You” to lapse into the self-parodic sourness and solipsism of “Sue Me, Sue You Blues” from Living In The Material World. Brought down by the increasingly widespread criticism of his output (a mood darkened by his own drinking and drugging), he responded through some of the songs on Extra Texture, a set of keyboard-based tunes, recorded mostly in Los Angeles, on which he plays very little guitar but lays into those considered responsible for his depressed state, albeit in a voice whose fragility hints at inner turmoil. The pounding “You”, released as the first single, offers a rare moment of something approaching good cheer. A return to a happier frame of mind would lie around the corner, once he had been freed from the deal with EMI and formed a new and lasting relationship with Olivia Arias, but only the most devoted Apple Scruff could truly love Extra Texture, or its two immediate predecessors, now. Wonderwall Music, however, documents an innocent optimism that will always be worth a listen. Richard Williams

The quiet Beatle’s escape attempts remastered…

George Harrison wasn’t the first to attempt an escape from the Beatles’ gilded cage – that was an exasperated Ringo, during the making of the White Album – but he was the first to prepare for a different existence after the inevitable end of the collective dream. In 1968 he became the first to make an album, Wonderwall Music, under his own name. A year later he was the first to go on the road with a group of musicians other than his fellow Mop Tops, namely Delaney and Bonnie and their fashionable friends, including Eric Clapton and Leon Russell. With these gestures he had built a platform for a new life.

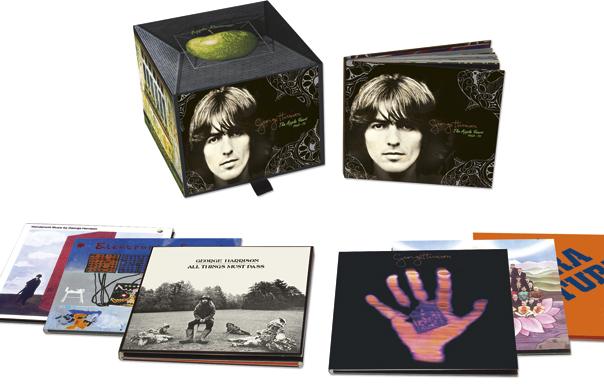

Wonderwall Music is the first item in this new box set of digitally remastered studio albums from Harrison’s Apple period. Written for Joe Massot’s film, which starred the unlikely combination of Jane Birkin, Jack McGowran, Irene Handl and Richard Wattis, it is a treat from start to finish. With no previous experience of writing soundtracks, Harrison recorded the music in Bombay studio and London, edited the results with the use of a stopwatch while watching Massot’s unfinished footage.

More than four and a half decades later the 18 tracks sound like an exploded diagram of a Beatles album, as viewed from Harrison’s off-centre perspective. Just about all the elements of the group’s overtly experimental period (1965-68) are there. Dreamy miniature ragas, featuring the ululations of the double-reed shenai (the opening “Microbes”, for example), give way to a pub knees-up gatecrashed by a Dixieland band (“Drilling a Home”), to the bones of early acid-rock songs (“Red Lady Too” and “Party Seacombe”), to a snatch of clippity-clop cowboy music called, of all things, “Cowboy Music”, and to a chant of “Om” accompanied by a harmonium. “Ski-ing” juxtaposes rock and raga, opening with an urgent guitar solo that sounds very much like Eric Clapton. “Dream Scene” is a collage of found sounds, anticipating Lennon’s “Revolution No 9”.

If the Beatles’ collective sense of humour, a larky surrealism best preserved in their fan club Christmas flexidiscs, was largely inherited from the Goons, then the inspiration for Harrison’s Electronic Music in 1969 surely came from another BBC institution of their formative years: the Radiophonic Workshop. On this album – first released on the Zapple label, Apple’s short-lived experimental subsidiary – we witness the joy of a boy with a new toy as Harrison spends 44 minutes discovering the sounds to be coaxed from a Moog synthesiser. Apparently he had some outside help: Bernie Krause, a pioneer of the new instrument, later claimed that a passage on the second side of the original LP release was lifted straight from a lesson he gave Harrison in how to operate the device.

With no pretensions to melody, harmony, pulse or any serious conceptual thinking, Electronic Music sounds like what you might get if you taped a contact microphone to the stomach of a digestively challenged robot: a lot of random rumbling, squeaking, hissing and groaning. A message appeared on the sleeve, credited to one Arthur Wax: “There are a lot of people around, making a lot of noise; here’s some more.” That still sums it up.

After these two albums, All Things Must Pass reasserted Harrison’s status as a songwriter whose work had once earnt its place, albeit a lesser one, alongside that of Lennon and McCartney, whose initial solo efforts, with their reversion to rockabilly and skiffle primitivism, he instantly eclipsed. A lavishly packaged triple album, it benefited from the attention of Phil Spector, whose well known production techniques – more instruments, more echo — served to disguise the whiny, monotonous tendency of Harrison’s voice, the preachiness of his lyrics and the inconsistent quality of his melodic gift. “My Sweet Lord” provided the worldwide hit and retains its surging power, as do “Beware of Darkness”, “What is Life” and “Awaiting on You All”. Nothing, however, can redeem the turgid instrumental jams – featuring Clapton, Billy Preston, Ginger Baker, Dave Mason and others – that made up the original third LP.

Without Spector to enrich his sonic environment, Harrison’s subsequent albums lapsed into a drabness only sporadically relieved by something like his version of the Everly Brothers’ “Bye Bye Love”, from the widely panned Dark Horse, where he sought the kind of return to bare-bones rock and roll simplicity that Lennon had achieved with “Instant Karma”. A man so rich in material resource and spiritual support had allowed the concerns first expressed in “Taxman” and “Within You, Without You” to lapse into the self-parodic sourness and solipsism of “Sue Me, Sue You Blues” from Living In The Material World.

Brought down by the increasingly widespread criticism of his output (a mood darkened by his own drinking and drugging), he responded through some of the songs on Extra Texture, a set of keyboard-based tunes, recorded mostly in Los Angeles, on which he plays very little guitar but lays into those considered responsible for his depressed state, albeit in a voice whose fragility hints at inner turmoil. The pounding “You”, released as the first single, offers a rare moment of something approaching good cheer.

A return to a happier frame of mind would lie around the corner, once he had been freed from the deal with EMI and formed a new and lasting relationship with Olivia Arias, but only the most devoted Apple Scruff could truly love Extra Texture, or its two immediate predecessors, now. Wonderwall Music, however, documents an innocent optimism that will always be worth a listen.

Richard Williams