Great snakes! After years in the wilderness, Hüsker Dü founder returns to the garden... No stranger to wild imaginings, Hüsker Dü co-pilot Grant Hart nailed his bewildering colours to the mast with the Nova Mob’s 1991 album The Last Days of Pompeii; an apocalyptic fantasy which wove together the eruption of Vesuvius, Nazi rocket scientist Wernherr von Braun, and Brer Rabbit. A long spell in self-released exile, it seems, has done little to temper his taste for the unconventional. Taking its cue from an unpublished William Burroughs remake of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, which casts the angels as an alien race and characterises God as former US President Harry S Truman, his hour-long Domino debut The Argument weeds out the religious overtones from the 17th century original, reconfiguring Lucifer’s fall from God’s right hand, and Adam and Eve’s exile from Eden as flesh-and-blood drama. “I like the big canvas, I guess,” he tells Uncut. “You can fling the metaphors round a little more.” However, for all of the high-concept backstory, The Argument is no dry intellectual exercise – perhaps because those themes of sin, temptation, betrayal and exile are echoed so forcefully in Hart’s life. During the album’s genesis, his elderly parents were defrauded of most of their savings by a rogue care home nurse, and then his own house, in which his family had lived since it was built in 1919, burned down. He may be channelling Lucifer as he sings “I am looking to escape from, this decimated hellscape,” on the mournful “I Will Never See My Home”, but the 52-year-old knows just how cruel acts of God can be. Certainly, Hart’s fortunes since the demise of Hüsker Dü have been very different to those of Bob Mould. In his autobiography, See A Little Light, Mould asserted that Hart’s heroin problem heralded the end of that band; a claim which rankles Hart. Whatever, at Hüsker Dü’s peak, Mould and Hart drove each other on to extraordinary heights, with three unbelievable psychedelic hardcore records – Zen Arcade, New Day Rising and Flip Your Wig –in the space of 18 months. An extraordinary writer, Mould is also an astute operator; whatever demons beset him, he remains on the move, and when – as with 2002’s auto-tune frenzy Modulate and the clubbed-up Long Playing Grooves – he headed off at a tangent that his small ‘c’ conservative audience could not handle, he was quick to snap back to the formula. Hart, meanwhile works, much as he talks – slowly, and with long pauses for reflection. In contrast to Mould’s focused productivity, Hart is a little more erratic, his work occasionally wanting a little polish. You don’t get much sense of a masterplan. Having come clean physically and emotionally on his homemade 1989 debut Intolerance a showcase for his breezy, soulful voice and understated songwriting, whatever momentum was built up with two Nova Mob albums in relatively quick succession soon dissipated. It took ten years for Hart to follow up 1999’s Good News For Modern Man with the equally amiable Hot Wax, making the relatively swift arrival of (i)The Argument(i) – delirious but fully formed – a bolt from the blue. Hüsker Dü aficionados will welcome “Morning Star” and the Buddy Holly-ish “Letting Me Out”, clearly plucked from the same tree of pop knowledge as past triumphs like “Every Everything” and “2541”, but foot-tappers are not (i)The Argument(i)’s stock in trade. Bolted to the story arc of Hart’s storm in heaven is some of the most ambitious and downright incongruous music of his career. “Underneath The Apple Tree”, may be the point when the weak cave in to the temptation to press the “off” button, especially the bit where the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band-influenced serpent offers Eve “beautiful fruit, so lovely, pleasing to the eye - you can eat it off the vine or bake it up into a pie”. Patience may be stretched further by “Awake Arise”, which sounds like a post rock version of Les Miserables – Godspell You Black Emperor, perhaps. Then there’s the hard rock hallelujah “It Isn’t Love” – “He will corrupt you, he will hurt you, he will try to steal your virtue,” Hart sings, blundering into the Euro-pomp Narnia of Aphrodite’s Child’s 1972 dramatisation of the Apocalypse of St John, “666”. Not all of the theatre is absurd, though. Gaunt and daunting, the title track hits a pitch that is bizarre but unequivocally compelling, Hart playing both innocence and experience as his characters engage in a rhetorical life-and-death-battle with just a wheezing harmonium and a set of windchimes for company. A magnificent lyrical double-helix, Hart chases his serpent’s tail, the last words of each portentous utterance morphing into the first of the next; “…Hands are unfamiliar to a snake/Snake why you tempt me, why the bother?/Bother not with laws I see right through them/Through them he has told us his demands/Demand to know exactly what’s at stake…” And so on for six riveting minutes. Dire retribution is meted out in the frenzied “Run For The Wilderness”, but The Argument trails off on a stylish offbeat with the shoo-be-doos and whoah-whoahs of the Bob Dylan-ish “For Those Two High Aspiring”, cosmic drama drawn down to mortal brass tacks. “Every breath brings you closer to your death, what a laugh what a laugh,” shrugs the Minnesotan, as he waves the first couple away. “Smile you unhappy exile.” Burned out, maybe, but in no danger of fading away, Hart’s eternally rudimentary musicianship means The Argument has been moulded from little more than a handful of dust and a spare rib, but there is something of the divine in its living, breathing whole. Rickety in construction, and occasionally ropey in execution, it holds up as a work of single-minded, lunatic conviction. Devilishly idiosyncratic, perhaps. But still on the side of the angels. Jim Wirth Q&A GRANT HART The Argument is partly based on an unissued William Burroughs treatment of Paradise Lost. How did that connection with Burroughs’ and his assistant James Grauerholz come about? We met through Giorno poetry systems when Hüsker Dü were asked to appear on the Diamond Hidden In The Mouth Of A Corpse compilation. I didn’t get a hold of Lost Paradise per se but it was sitting on the table when I came over to visit James. It was barely more than an outline – just a few pages. It is like a science fiction take on Milton, where the fallen angels were people from another interstellar race and God was personified as Harry Truman. The atom bomb was part of the whole war in heaven scenario. Is “The Argument” more Burroughs than Milton? I would say it’s pretty evenly divided. The timeline is the same as Milton – I have kept the flashbacks where they should be – but what I was eager to do was to excise as much as possible the religious content. I have turned it more into an interpersonal thing where Lucifer reacts too strongly to being rejected with God paying more attention to the new Christ rather than the old angels. Lucifer kind of goes off because he is given to the opposite of love – he wants to destroy love wherever he finds it. Why is the story so compelling for you? Just the sheer drama of it and the archetypes you get to play with. The earliest songs that I wrote had to do with the expulsion from the garden and the lake of fire, and the reawakening of Lucifer as Satan. I had these two primordial songs cooking and I felt Paradise Lost was going to be a nice vehicle for these two songs. I investigated it more but the white light golden moment was when I discovered the Burroughs manuscript. In a way it was real liberating having a thousand song topics just drop into your lap. After losing your home in a fire, did you feel there were parallels with that and Adam and Eve being driven out of Eden? The events are there. In the dedication of the album I have thanked those who rescued me from the lake of fire and helped me build my new Pandaemonium. Losing your own private little museum can be quite liberating – the possessions that you accumulate the things that you save over the course of at that stage 49 years is kind of an exhibition devoted to yourself. Every day I think of something and its: ‘Oops, don’t have it anymore.’ ‘I should wear my plaid shirt – oops, don’t have it anymore.’ Do I find that liberating? Fortunately yes. Who plays on the record? It’s mostly me. I was heavily influenced by Roy Wood. He played far more instruments than I am capable of – I tend to play a lot of keyboards and rhythm guitar to make up for my inefficiency at lead guitar. I saw how you were able to do it pretty early on from the example of Roy Wood. What is the appeal of making concept albums? I like the big canvas, I guess – you can fling the metaphors round a little more. You can use the same words twice! You have had a bit of a stop start career. Do you feel you are on a more even keel after signing to Domino? This is the first time since the days of the Nova Mob that I have signed a contract where there is the smallest glint of hope that there will be a follow-up record. I do not function well in the world of the salesman, shopping a record to labels. I can’t shove myself down people’s throats – they have to want it and come and get it. You worked in record shops when you were younger. Were you a prog rock fan? I worked in a few record stores. Vinyl was still king. I was 14 and had 1500 albums and I think a couple of them were King Crimson. There was a Yes album in there. Oh, Brain Salad Surgery – Emerson Lake and Palmer – how prog can you get? Hardcore was more didactic- if you were listening to something else you were wasting time when you could have been listening to something local so you could be supporting you scene, man. Do you still think people compare you to Bob Mould? People seem to think they can’t like me and like Bob’s music. There are these people who came on board around the time of Sugar who have heard that there is this bad guy in Bob’s past who was vanquished by Bob like a dragon. There’s more productive people to compare myself to. Am I the Satan that fell from Bob’s right hand? I’m a whole different kind of Satan… INTERVIEW: JIM WIRTH

Great snakes! After years in the wilderness, Hüsker Dü founder returns to the garden…

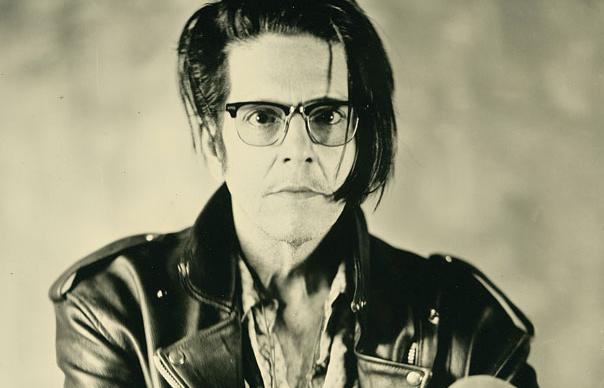

No stranger to wild imaginings, Hüsker Dü co-pilot Grant Hart nailed his bewildering colours to the mast with the Nova Mob’s 1991 album The Last Days of Pompeii; an apocalyptic fantasy which wove together the eruption of Vesuvius, Nazi rocket scientist Wernherr von Braun, and Brer Rabbit. A long spell in self-released exile, it seems, has done little to temper his taste for the unconventional.

Taking its cue from an unpublished William Burroughs remake of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, which casts the angels as an alien race and characterises God as former US President Harry S Truman, his hour-long Domino debut The Argument weeds out the religious overtones from the 17th century original, reconfiguring Lucifer’s fall from God’s right hand, and Adam and Eve’s exile from Eden as flesh-and-blood drama. “I like the big canvas, I guess,” he tells Uncut. “You can fling the metaphors round a little more.”

However, for all of the high-concept backstory, The Argument is no dry intellectual exercise – perhaps because those themes of sin, temptation, betrayal and exile are echoed so forcefully in Hart’s life. During the album’s genesis, his elderly parents were defrauded of most of their savings by a rogue care home nurse, and then his own house, in which his family had lived since it was built in 1919, burned down. He may be channelling Lucifer as he sings “I am looking to escape from, this decimated hellscape,” on the mournful “I Will Never See My Home”, but the 52-year-old knows just how cruel acts of God can be.

Certainly, Hart’s fortunes since the demise of Hüsker Dü have been very different to those of Bob Mould. In his autobiography, See A Little Light, Mould asserted that Hart’s heroin problem heralded the end of that band; a claim which rankles Hart. Whatever, at Hüsker Dü’s peak, Mould and Hart drove each other on to extraordinary heights, with three unbelievable psychedelic hardcore records – Zen Arcade, New Day Rising and Flip Your Wig –in the space of 18 months.

An extraordinary writer, Mould is also an astute operator; whatever demons beset him, he remains on the move, and when – as with 2002’s auto-tune frenzy Modulate and the clubbed-up Long Playing Grooves – he headed off at a tangent that his small ‘c’ conservative audience could not handle, he was quick to snap back to the formula. Hart, meanwhile works, much as he talks – slowly, and with long pauses for reflection. In contrast to Mould’s focused productivity, Hart is a little more erratic, his work occasionally wanting a little polish. You don’t get much sense of a masterplan.

Having come clean physically and emotionally on his homemade 1989 debut Intolerance a showcase for his breezy, soulful voice and understated songwriting, whatever momentum was built up with two Nova Mob albums in relatively quick succession soon dissipated. It took ten years for Hart to follow up 1999’s Good News For Modern Man with the equally amiable Hot Wax, making the relatively swift arrival of (i)The Argument(i) – delirious but fully formed – a bolt from the blue.

Hüsker Dü aficionados will welcome “Morning Star” and the Buddy Holly-ish “Letting Me Out”, clearly plucked from the same tree of pop knowledge as past triumphs like “Every Everything” and “2541”, but foot-tappers are not (i)The Argument(i)’s stock in trade. Bolted to the story arc of Hart’s storm in heaven is some of the most ambitious and downright incongruous music of his career. “Underneath The Apple Tree”, may be the point when the weak cave in to the temptation to press the “off” button, especially the bit where the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band-influenced serpent offers Eve “beautiful fruit, so lovely, pleasing to the eye – you can eat it off the vine or bake it up into a pie”.

Patience may be stretched further by “Awake Arise”, which sounds like a post rock version of Les Miserables – Godspell You Black Emperor, perhaps. Then there’s the hard rock hallelujah “It Isn’t Love” – “He will corrupt you, he will hurt you, he will try to steal your virtue,” Hart sings, blundering into the Euro-pomp Narnia of Aphrodite’s Child’s 1972 dramatisation of the Apocalypse of St John, “666”.

Not all of the theatre is absurd, though. Gaunt and daunting, the title track hits a pitch that is bizarre but unequivocally compelling, Hart playing both innocence and experience as his characters engage in a rhetorical life-and-death-battle with just a wheezing harmonium and a set of windchimes for company. A magnificent lyrical double-helix, Hart chases his serpent’s tail, the last words of each portentous utterance morphing into the first of the next; “…Hands are unfamiliar to a snake/Snake why you tempt me, why the bother?/Bother not with laws I see right through them/Through them he has told us his demands/Demand to know exactly what’s at stake…” And so on for six riveting minutes.

Dire retribution is meted out in the frenzied “Run For The Wilderness”, but The Argument trails off on a stylish offbeat with the shoo-be-doos and whoah-whoahs of the Bob Dylan-ish “For Those Two High Aspiring”, cosmic drama drawn down to mortal brass tacks. “Every breath brings you closer to your death, what a laugh what a laugh,” shrugs the Minnesotan, as he waves the first couple away. “Smile you unhappy exile.”

Burned out, maybe, but in no danger of fading away, Hart’s eternally rudimentary musicianship means The Argument has been moulded from little more than a handful of dust and a spare rib, but there is something of the divine in its living, breathing whole. Rickety in construction, and occasionally ropey in execution, it holds up as a work of single-minded, lunatic conviction. Devilishly idiosyncratic, perhaps. But still on the side of the angels.

Jim Wirth

Q&A

GRANT HART

The Argument is partly based on an unissued William Burroughs treatment of Paradise Lost. How did that connection with Burroughs’ and his assistant James Grauerholz come about?

We met through Giorno poetry systems when Hüsker Dü were asked to appear on the Diamond Hidden In The Mouth Of A Corpse compilation. I didn’t get a hold of Lost Paradise per se but it was sitting on the table when I came over to visit James. It was barely more than an outline – just a few pages. It is like a science fiction take on Milton, where the fallen angels were people from another interstellar race and God was personified as Harry Truman. The atom bomb was part of the whole war in heaven scenario.

Is “The Argument” more Burroughs than Milton?

I would say it’s pretty evenly divided. The timeline is the same as Milton – I have kept the flashbacks where they should be – but what I was eager to do was to excise as much as possible the religious content. I have turned it more into an interpersonal thing where Lucifer reacts too strongly to being rejected with God paying more attention to the new Christ rather than the old angels. Lucifer kind of goes off because he is given to the opposite of love – he wants to destroy love wherever he finds it.

Why is the story so compelling for you?

Just the sheer drama of it and the archetypes you get to play with. The earliest songs that I wrote had to do with the expulsion from the garden and the lake of fire, and the reawakening of Lucifer as Satan. I had these two primordial songs cooking and I felt Paradise Lost was going to be a nice vehicle for these two songs. I investigated it more but the white light golden moment was when I discovered the Burroughs manuscript. In a way it was real liberating having a thousand song topics just drop into your lap.

After losing your home in a fire, did you feel there were parallels with that and Adam and Eve being driven out of Eden?

The events are there. In the dedication of the album I have thanked those who rescued me from the lake of fire and helped me build my new Pandaemonium. Losing your own private little museum can be quite liberating – the possessions that you accumulate the things that you save over the course of at that stage 49 years is kind of an exhibition devoted to yourself. Every day I think of something and its: ‘Oops, don’t have it anymore.’ ‘I should wear my plaid shirt – oops, don’t have it anymore.’ Do I find that liberating? Fortunately yes.

Who plays on the record?

It’s mostly me. I was heavily influenced by Roy Wood. He played far more instruments than I am capable of – I tend to play a lot of keyboards and rhythm guitar to make up for my inefficiency at lead guitar. I saw how you were able to do it pretty early on from the example of Roy Wood.

What is the appeal of making concept albums?

I like the big canvas, I guess – you can fling the metaphors round a little more. You can use the same words twice!

You have had a bit of a stop start career. Do you feel you are on a more even keel after signing to Domino?

This is the first time since the days of the Nova Mob that I have signed a contract where there is the smallest glint of hope that there will be a follow-up record. I do not function well in the world of the salesman, shopping a record to labels. I can’t shove myself down people’s throats – they have to want it and come and get it.

You worked in record shops when you were younger. Were you a prog rock fan?

I worked in a few record stores. Vinyl was still king. I was 14 and had 1500 albums and I think a couple of them were King Crimson. There was a Yes album in there. Oh, Brain Salad Surgery – Emerson Lake and Palmer – how prog can you get? Hardcore was more didactic- if you were listening to something else you were wasting time when you could have been listening to something local so you could be supporting you scene, man.

Do you still think people compare you to Bob Mould?

People seem to think they can’t like me and like Bob’s music. There are these people who came on board around the time of Sugar who have heard that there is this bad guy in Bob’s past who was vanquished by Bob like a dragon. There’s more productive people to compare myself to. Am I the Satan that fell from Bob’s right hand? I’m a whole different kind of Satan…

INTERVIEW: JIM WIRTH