Country music has detonated its share of Big Bangs. The 1927 Bristol Sessions, featuring initial recordings by Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family, was one; Elvis Presley’s seismic Sun Sessions, firmly rooted in the rural Deep South, turned the page into the rock’n’roll era. Long-obscured, but just as explosive, Hank Williams’ Complete Mother’s Best Collection – vintage, high-calibre radio tapes finally offered up in their entirety – might be considered the ultimate aftershock. A dizzying cache of 143 performances heard by a handful of souls once, then consigned to a trash dumpster until Grand Ole Opry photographer Les Leverett salvaged them in the 1960s, the Mother’s Best tapes are funny, poignant, culturally edifying (witness, especially, a window on unenlightened 1950s gender relations), musically dazzling, and a breathtaking document of a transcendent artist in a bygone era. Bear Family’s spectacular boxset, augmented by fine-as-can-be-expected sound and Colin Escott’s perceptive notes, presents a daunting, sprawling body of work, catching Williams at an artistic peak, armed with the will and freedom to reflect, explore and experiment. Hank Williams, of course, is the father of country music, and the outlines of his meteoric fame and tragic death are well known. A hillbilly Shakespeare who could pen wrenching, soul-searching ballads and rattletrap honky-tonk, Williams’ ‘high lonesome’ tenor and everyman poetry have resounded down through the decades. He recorded for just six years (1947-52), yet left behind a preposterously influential body of work. The biggest hits – “Your Cheatin’ Heart”, “Hey Good Lookin’”, “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”– are building blocks of American music, yet hardly brush the surface of his grim biography. New Year’s Day 1953, on his way to a gig in Canton, Ohio, he was found dead in the backseat of his Cadillac, aged just 29. In ’51, though, Williams was the hottest star in the country, striking a rich vein with bleak odes to broken love affairs like “Cold, Cold Heart” and “I Can’t Help It (If I’m Still In Love With You)”. In amongst the heavy touring, Grand Ole Opry appearances, and recording dates, Williams, his wife Audrey, and his peerless combo the Drifting Cowboys set up shop at Nashville’s WSM, cutting scores of 15-minute radio slots under the auspices of the local flour mill. The shows – loose, casual, filled with sales pitches, cornball jokes, and idle banter about this year’s crops – reflect the convivial, neighbourly tone of master of ceremonies, one Cousin Louie Buck. The inanities of self-rising cornmeal and garden seed coupons vanish, though, when Williams opens his mouth to sing. Authoritative, mesmerising, passionate, riveting, he consistently throws his all into the music, wringing untold pathos out of morbid ballads like “The Blind Child’s Prayer” and “The First Fall of Snow”, kicking up his heels on oldies like “Howlin’ At The Moon”. The band, particularly steel guitar wizard Don Helms and fiddler Jerry Rivers, are spot-on, virtuosos in mood, revelling in the songs’ grit, sometimes adding churchy harmonies. The clincher, though, is Williams’ astounding repertoire. He digs deep into American music, unearthing lost folk, blues, country, and gospel nuggets of most any provenance (see “I Blotted Your Happy Schooldays”) much as Bob Dylan and The Band did on The Basement Tapes sessions. From covers of contemporary hits by Roy Acuff and Ernest Tubb, to dragging spirituals out of dusty hymnbooks, to parables proffered by his alter-ego, Luke the Drifter, Williams is delightfully all over the map. Along the way he revisits his first studio record, “Calling You”, debuts a tentative take of perhaps his signature song, “Cold, Cold Heart” and delves into virtually everything from his back-catalogue. Friends drop by on occasion, such as country hitmakers Johnnie & Jack, and The Drifting Cowboys, for their part, chime in with stellar instrumentals from the American songbook. There are caveats: you’ll learn more about chick feed, self-rising cornmeal, and fluffy biscuits than you think imaginable, but the pitches get tiresome on extended listening. The Williams estate has also disingenuously parsed some of this material out on previous releases. Most offending by far, though, are Audrey Williams’ inexplicable vocal solos. Still, the simple, soulful beauty of much of this music far outweighs any reservation, and any one of the sublime “Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain”, a nigh-on perfect “Cool Water”, “Move It On Over” or Fred Rose’s chilling “The Prodigal Son” – to cite just a fraction of the highlights – would repay the price of admission. Or as they say here: “Hasta la biscuit, baby!” Luke Torn

Country music has detonated its share of Big Bangs. The 1927 Bristol Sessions, featuring initial recordings by Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family, was one; Elvis Presley’s seismic Sun Sessions, firmly rooted in the rural Deep South, turned the page into the rock’n’roll era. Long-obscured, but just as explosive, Hank Williams’ Complete Mother’s Best Collection – vintage, high-calibre radio tapes finally offered up in their entirety – might be considered the ultimate aftershock.

A dizzying cache of 143 performances heard by a handful of souls once, then consigned to a trash dumpster until Grand Ole Opry photographer Les Leverett salvaged them in the 1960s, the Mother’s Best tapes are funny, poignant, culturally edifying (witness, especially, a window on unenlightened 1950s gender relations), musically dazzling, and a breathtaking document of a transcendent artist in a bygone era. Bear Family’s spectacular boxset, augmented by fine-as-can-be-expected sound and Colin Escott’s perceptive notes, presents a daunting, sprawling body of work, catching Williams at an artistic peak, armed with the will and freedom to reflect, explore and experiment.

Hank Williams, of course, is the father of country music, and the outlines of his meteoric fame and tragic death are well known. A hillbilly Shakespeare who could pen wrenching, soul-searching ballads and rattletrap honky-tonk, Williams’ ‘high lonesome’ tenor and everyman poetry have resounded down through the decades. He recorded for just six years (1947-52), yet left behind a preposterously influential body of work. The biggest hits – “Your Cheatin’ Heart”, “Hey Good Lookin’”, “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”– are building blocks of American music, yet hardly brush the surface of his grim biography. New Year’s Day 1953, on his way to a gig in Canton, Ohio, he was found dead in the backseat of his Cadillac, aged just 29.

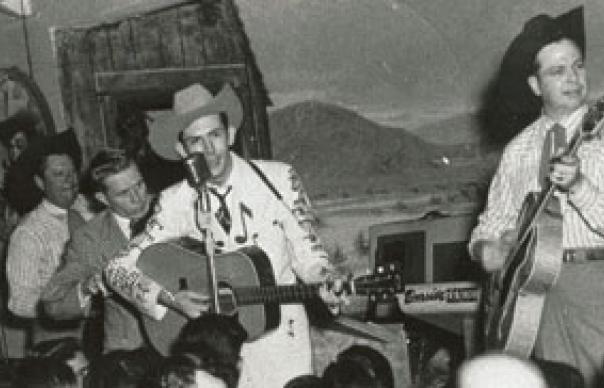

In ’51, though, Williams was the hottest star in the country, striking a rich vein with bleak odes to broken love affairs like “Cold, Cold Heart” and “I Can’t Help It (If I’m Still In Love With You)”. In amongst the heavy touring, Grand Ole Opry appearances, and recording dates, Williams, his wife Audrey, and his peerless combo the Drifting Cowboys set up shop at Nashville’s WSM, cutting scores of 15-minute radio slots under the auspices of the local flour mill. The shows – loose, casual, filled with sales pitches, cornball jokes, and idle banter about this year’s crops – reflect the convivial, neighbourly tone of master of ceremonies, one Cousin Louie Buck.

The inanities of self-rising cornmeal and garden seed coupons vanish, though, when Williams opens his mouth to sing. Authoritative, mesmerising, passionate, riveting, he consistently throws his all into the music, wringing untold pathos out of morbid ballads like “The Blind Child’s Prayer” and “The First Fall of Snow”, kicking up his heels on oldies like “Howlin’ At The Moon”. The band, particularly steel guitar wizard Don Helms and fiddler Jerry Rivers, are spot-on, virtuosos in mood, revelling in the songs’ grit, sometimes adding churchy harmonies.

The clincher, though, is Williams’ astounding repertoire. He digs deep into American music, unearthing lost folk, blues, country, and gospel nuggets of most any provenance (see “I Blotted Your Happy Schooldays”) much as Bob Dylan and The Band did on The Basement Tapes sessions. From covers of contemporary hits by Roy Acuff and Ernest Tubb, to dragging spirituals out of dusty hymnbooks, to parables proffered by his alter-ego, Luke the Drifter, Williams is delightfully all over the map.

Along the way he revisits his first studio record, “Calling You”, debuts a tentative take of perhaps his signature song, “Cold, Cold Heart” and delves into virtually everything from his back-catalogue. Friends drop by on occasion, such as country hitmakers Johnnie & Jack, and The Drifting Cowboys, for their part, chime in with stellar instrumentals from the American songbook.

There are caveats: you’ll learn more about chick feed, self-rising cornmeal, and fluffy biscuits than you think imaginable, but the pitches get tiresome on extended listening. The Williams estate has also disingenuously parsed some of this material out on previous releases. Most offending by far, though, are Audrey Williams’ inexplicable vocal solos.

Still, the simple, soulful beauty of much of this music far outweighs any reservation, and any one of the sublime “Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain”, a nigh-on perfect “Cool Water”, “Move It On Over” or Fred Rose’s chilling “The Prodigal Son” – to cite just a fraction of the highlights – would repay the price of admission. Or as they say here: “Hasta la biscuit, baby!”

Luke Torn