The disorderly story of the architect of the Factory Records sound... Martin Hannett’s gravestone is inscribed with the legend “Creator of the Manchester Sound”, but the fact that he lay in unmarked ground for 17 years shows that he hasn’t always been revered. This ambivalence to his artistic single-mindedness was shared by the artists he produced. Joy Division, whose two albums can be viewed as Hannett’s most significant legacy, were nonplussed by the sonic surgery applied to their 1979 debut Unknown Pleasures. And U2, who sought him out for their 1980 single, “11 O’Clock Tick Tock”, swiftly moved on, fearing they might become just another Martin Hannett group. Needless to say, time has softened attitudes. Peter Hook notes in this lo-fi documentary that, “without Martin, [Joy Division’s music] would definitely not have lasted because we would have made it upfront, punk, all fast, and no depth, no atmosphere.” Factory boss Tony Wilson puts it more simply, saying Hannett was aware of the way music was changing and “he changed music”. With hindsight, it’s clear that Hannett’s contribution was to hijack the energy of punk and apply a pre-punk sensibility. His approach endures in dance music, partly because of his influence on New Order, who couldn’t help inhaling his methods, but also because of his interest in rhythm. He had dabbled in various improvisational combos, jamming with the likes of Magazine’s Dave Formula and The Durutti Column’s Bruce Mitchell in a style that betrayed an interest in The Grateful Dead. Even then, he tended to view the bass as a lead instrument - a trick that would define Joy Division’s sound. He played it with a Zippo lighter. Hannett was a hi-fi buff. “He would starve just to get money to buy his expensive Quad bollocks,” Mitchell observes. He studied chemical engineering, and applied his studies recreationally, using - as Wilson noted elsewhere - “every fucking drug”. Prior to Factory, he was involved in a musicians’ co-op, and Rabid Records, which released Jilted John before morphing into Absurd Records, whose releases included an unplayable picture disc, decorated with pictures cut from The Dandy. He managed John Cooper Clarke, and played in The Invisible Girls, enhancing the punk poet’s voice by recording him shouting into a lift shaft. The significant part of the story begins with the austere sound he drought to Buzzcocks’ DIY EP Spiral Scratch. Hannett’s association with Tony Wilson began when he urged him to go and see Slaughter and the Dogs (in an odd pre-echo, one of their posters had the slogan “Slaughter and the Dogs Will Tear You Apart”). The producer’s influence on Joy Division is obvious. His approach to recording them was painstaking, with the emphasis on pain. Stephen Morris’s drums were literally deconstructed, because Hannett claimed he could dear the springs inside. By the time of Closer, the group’s patience was wearing thin. Hook - the only band member who owned a cassette player - had to borrow petrol money to let the rest of the band hear “Love Will Tear Us Apart” in his car. “It sounded bloody awful.” There was a fall-out with Factory - not explored - and a reconciliation. He recorded Bummed with The Happy Mondays, and had a tilt at The Stone Roses (“he was 5% sound and 95% aesthetic,” they note). Creatively, thanks to his drug and alcohol intake, he faded out, dying in 1991. It’s a messy tale, and with a four hour running time, it sprawls. Filmmaker Chris Hewitt follows his own interest in sound, so while there is much talk of echo plates, the human story is sometimes forgotten. The picture and sound quality are poor, but there is valuable archive footage, some of it rescued from an abandoned documentary by Anthony Ryan Carter, for which Jon Ronson interviewed Tony Wilson. The key to the Factory sound? That would be the sound of a factory. Hannett apparently became fascinated by the beats he heard in the air-conditioning units at a Ferranti plant, and was inspired to locate music in unusual places: footsteps, lifts, cups smashing. Probed by Wilson, he offers a simpler explanation. The snare drum, he suggests, is the essence of rock’n’roll. “Playing the offbeats with a good deal of vigour.” EXTRAS: None. Alastair McKay

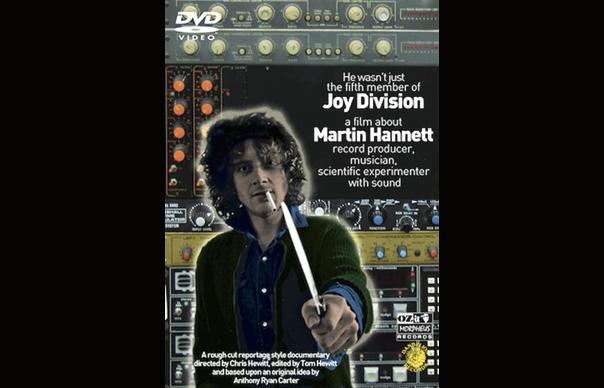

The disorderly story of the architect of the Factory Records sound…

Martin Hannett’s gravestone is inscribed with the legend “Creator of the Manchester Sound”, but the fact that he lay in unmarked ground for 17 years shows that he hasn’t always been revered. This ambivalence to his artistic single-mindedness was shared by the artists he produced. Joy Division, whose two albums can be viewed as Hannett’s most significant legacy, were nonplussed by the sonic surgery applied to their 1979 debut Unknown Pleasures. And U2, who sought him out for their 1980 single, “11 O’Clock Tick Tock”, swiftly moved on, fearing they might become just another Martin Hannett group.

Needless to say, time has softened attitudes. Peter Hook notes in this lo-fi documentary that, “without Martin, [Joy Division’s music] would definitely not have lasted because we would have made it upfront, punk, all fast, and no depth, no atmosphere.” Factory boss Tony Wilson puts it more simply, saying Hannett was aware of the way music was changing and “he changed music”.

With hindsight, it’s clear that Hannett’s contribution was to hijack the energy of punk and apply a pre-punk sensibility. His approach endures in dance music, partly because of his influence on New Order, who couldn’t help inhaling his methods, but also because of his interest in rhythm. He had dabbled in various improvisational combos, jamming with the likes of Magazine’s Dave Formula and The Durutti Column’s Bruce Mitchell in a style that betrayed an interest in The Grateful Dead. Even then, he tended to view the bass as a lead instrument – a trick that would define Joy Division’s sound. He played it with a Zippo lighter.

Hannett was a hi-fi buff. “He would starve just to get money to buy his expensive Quad bollocks,” Mitchell observes. He studied chemical engineering, and applied his studies recreationally, using – as Wilson noted elsewhere – “every fucking drug”. Prior to Factory, he was involved in a musicians’ co-op, and Rabid Records, which released Jilted John before morphing into Absurd Records, whose releases included an unplayable picture disc, decorated with pictures cut from The Dandy. He managed John Cooper Clarke, and played in The Invisible Girls, enhancing the punk poet’s voice by recording him shouting into a lift shaft.

The significant part of the story begins with the austere sound he drought to Buzzcocks’ DIY EP Spiral Scratch. Hannett’s association with Tony Wilson began when he urged him to go and see Slaughter and the Dogs (in an odd pre-echo, one of their posters had the slogan “Slaughter and the Dogs Will Tear You Apart”). The producer’s influence on Joy Division is obvious. His approach to recording them was painstaking, with the emphasis on pain. Stephen Morris’s drums were literally deconstructed, because Hannett claimed he could dear the springs inside. By the time of Closer, the group’s patience was wearing thin. Hook – the only band member who owned a cassette player – had to borrow petrol money to let the rest of the band hear “Love Will Tear Us Apart” in his car. “It sounded bloody awful.”

There was a fall-out with Factory – not explored – and a reconciliation. He recorded Bummed with The Happy Mondays, and had a tilt at The Stone Roses (“he was 5% sound and 95% aesthetic,” they note). Creatively, thanks to his drug and alcohol intake, he faded out, dying in 1991.

It’s a messy tale, and with a four hour running time, it sprawls. Filmmaker Chris Hewitt follows his own interest in sound, so while there is much talk of echo plates, the human story is sometimes forgotten. The picture and sound quality are poor, but there is valuable archive footage, some of it rescued from an abandoned documentary by Anthony Ryan Carter, for which Jon Ronson interviewed Tony Wilson.

The key to the Factory sound? That would be the sound of a factory. Hannett apparently became fascinated by the beats he heard in the air-conditioning units at a Ferranti plant, and was inspired to locate music in unusual places: footsteps, lifts, cups smashing. Probed by Wilson, he offers a simpler explanation. The snare drum, he suggests, is the essence of rock’n’roll. “Playing the offbeats with a good deal of vigour.”

EXTRAS: None.

Alastair McKay