To fully appreciate James Szalapski’s sketchy documentary about the music of Nashville and Austin in 1975, you have to understand what the film isn’t. It is not a film about Outlaw country, though it does include footage of David Allan Coe playing a show in Tennessee State Prison. It’s not ev...

To fully appreciate James Szalapski’s sketchy documentary about the music of Nashville and Austin in 1975, you have to understand what the film isn’t. It is not a film about Outlaw country, though it does include footage of David Allan Coe playing a show in Tennessee State Prison.

It’s not even a film about New Country, though that was the working title, and it does include the teenage Steve Earle, who would be a leading player in what became known as the New Country movement a decade later. It is, slightly, a lament for a lost Nashville, because it was made at a time when country music was becoming more corporate, and the Grand Ole Opry was betraying its heritage by abandoning its historic home downtown in the Ryman Auditorium in favour of a soulless new venue in a theme park and hotel complex.

But really, the flashes of old Nashville filmed inside the old Wigwam Tavern are used as seasoning, and their links to the new music celebrated in the film are tangential. Certainly, the denizens of the Wigwam – the tavern’s owner, Big Mac McGowan, “Smoky Mountain” Glenn Stagner, and the extraordinary singer Peggy Brooks (about whom nothing is known) – are right to be bemused by the commercial turns taken by country music in the 1970s. But, then, a conversation in which someone suggested to Guy Clark that he was a country musician would have been a short one.

The film, in essence, is a beautiful accident. Szalapksi, a New York director who had previously worked on the Miss Nude America movie, had a plan, and he executed it. Roughly, this was to capture the mood and the lifestyle of a group of alternative, younger musicians who were operating on the fringes of the Nashville establishment. At the time, Music City was in a post-Kristofferson moment. The success of “Sunday Morning Coming Down” had given hope to a new generation of songwriters, who really had more to do with the folk revival than country. As a filmmaker, Szalapksi took a ‘direct cinema’ approach. There is no narrator, no interviewing. The resulting film is a collage. It has a point of view, but it’s not stated overtly. The music, and the imagery, do the talking.

It is probably a bit harsh to suggest that Szalapksi got lucky when he decided to focus on Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt. Both musicians had growing reputations at the time, even if major commercial success remained elusive. They were close friends too, offering different interpretations of a form of narrative songwriting that was particular to Texas. Neither man explains that in the film. Clark, an accomplished luthier, is pictured working on old guitar, while Townes offers a chaotic guided tour of the grounds surrounding his trailer home. (Drink, clearly, has been taken).

Then there is the music. Much of the best of it takes place at a Christmas Eve jam at Clark’s home, with the host, his songwriting artist wife Susanna, Rodney Crowell, Steve Earle and others swapping songs. The drunker they get, the harder they play, and they get pretty drunk. Meanwhile, in Austin, Townes plays “Waitin’ Around To Die”, and reduces his neighbour, ‘the walking blacksmith” Seymour Washington to tears. (The sleeve notes suggest that “Unk”, who had only a year to live, may have been playing to the camera, but that seems overly cynical).

A previous DVD reissue added an hour of extras, including more great clips from Clark, and John Hiatt (with hair!) doing “One For The One”. They’re included here. If anything, the extras show how Szalapski didn’t quite know what he had. With hindsight, the comic country monologues of Gamble Rogers should have been sacrificed, and the David Allan Coe material could have gone into a different film. But Szalapski wasn’t to know that history would judge Clark to be the true artist of the period, with Townes as his inebriated Tonto.

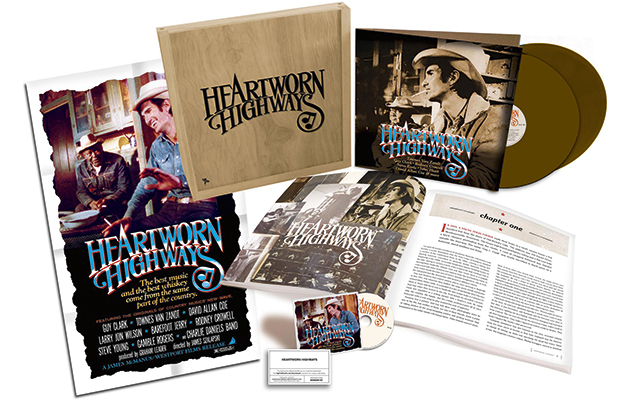

EXTRAS: A double vinyl soundtrack LP with five essential songs from Guy Clark, a couple from Townes, and three from Steve Earle. The album ends with a chaotic chorus of ‘Silent Night’, led by Rodney Crowell. Also included, an 80 page book with liner notes by Sam Sweet.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.</strong