4CD box set charting the ascendance of the blues’ most distinctive voice. O-wooo! Chester ‘Howling Wolf’ Burnett never did make an easy fit for the world, at least not until he became an overnight sensation at the age of 42, bursting onto the post-war blues scene to claim his place as one o...

4CD box set charting the ascendance of the blues’ most distinctive voice. O-wooo!

Chester ‘Howling Wolf’ Burnett never did make an easy fit for the world, at least not until he became an overnight sensation at the age of 42, bursting onto the post-war blues scene to claim his place as one of the music’s titans, a status time has only enhanced. His primal growl arrived as a force of nature – “This is where the soul of man never dies” producer Sam Phillips famously declared. No-one has ever sounded like Wolf, before or since.

The 97 tracks here document only the first decade of his recording career, and even then there are omissions from his tangled start – the sessions he cut for other labels – but they confirm him as a “true blues immortal” as Dick Shurman puts it in his liner notes. Present are only a clutch of the sides that branded a generation of Brit and U.S. bluesers and which they duly made into standards in the 1960s – the crooked lope of “Smokestack Lightning”, the hypnotic “Spoonful”, the forlorn “Sitting On Top Of The World” – but the extras and alternate takes amount to a serious treat. The whole package is delivered with restrained good taste, with a slew of evocative pictures and graphics, and a brace of classy essays, Peter Guralnick being the other scribe present. The crucible of 1950s Southside Chicago is brought to bubbling life.

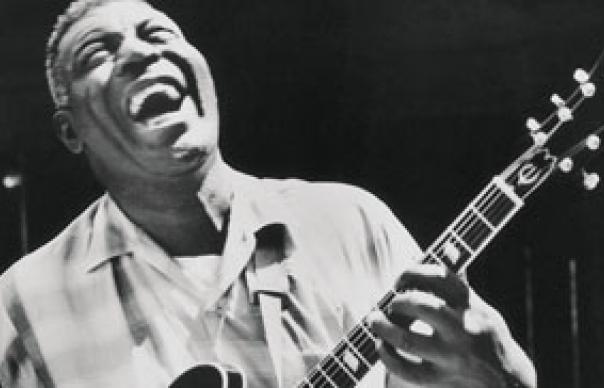

One thing that springs from those black and white photos is the sheer exuberance of Wolf, a hulking giant who was nonetheless always dapper. There’s an odd disconnect between his artful tie-pins and geniality and that gravel pit of a voice and the pain and anguish it conveys, a disjunction explained by his early life. The 1950s were a time of happiness and success for Wolf. The self-destructive ways of many of his peers were never a temptation. He was financially astute and happily married. Yet he remained stubborn and suspicious, and the scars of his previous life clearly ran deep: a troubled, dirt poor childhood in Mississippi that included estrangement from his mother, hard graft on his father’s farm, an unhappy spell in the army, the grinding life of an itinerant bluesman in the segregated south.

To the young Wolf, only music made sense of the world. The mentoring role of Charlie Patton, whom the twenty year old Wolf met in 1930, when Patton was top draw on the delta blues scene, was pivotal in shaping what followed. Wolf’s “Saddle My Pony”, for example, is a direct descendant of Patton’s “Pony Blues” and “Smokestack Lightning” itself is modeled on Patton’s “Moon Going Down”.

It’s astonishing it took so long for Wolf to get recorded – he was a celebrated performer first in Mississippi, then in Memphis, where he relocated. It took Sam Phillips, a visionary contemptuous of the south’s segregation code, to put him on disc, licensing tracks cut in his Memphis studio to Chess in Chicago. A third of what’s here originated with Phillips, who always cited Wolf as the purest, most instinctive talent of a roster that includes Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis and B.B. King.` Wolf’s decampment to Chicago and Chess in 1954 hurt Phillips badly.

Philips’ faith in Wolf was instantly rewarded when “Moaning At Midnight”/“How Many More Years” became a double-headed number one on the R&B charts. Both still sound bitingly fresh, setting Wolf’s buzz-saw vocals – punctuated by that trademark falsetto howl – and droning harp against the dazzle of Willie Johnson’s guitar, a mix of delta picking, T-Bone Walker be-bop, and proto power chords. Because microphones overloaded under the sheer power of Wolf’s voice, his rasp emerged as electrified as Johnson’s guitar, a delivery that was later imitated by DJ Wolfman Jack and Captain Beefheart.

It took Wolf a couple of years and a move to Chicago – he proudly drove there in his own station wagon – to top his debut. “Smokestack Lightning” and the menacing “Evil” surely did so, with “Baby How Long” another contender. Nonetheless the mid to late 1950s represent a lull in Wolf’s output after his spectacular arrival. Chess, flush with the success of Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, could afford to let him freewheel. Wolf recorded mostly self-written originals; simple songs about the pain of betrayed lovers, a parade of heartache, broken homes and his baby buying a train ticket “as long as my right arm”. Yet Wolf was capable of delicious irony on say, “Sitting On Top Of The World” (“She’s gone but I don’t worry”), and in “The Natchez Burning” he wrote a famous memorial for the 200 clubgoers killed in a 1940 Chicago fire.

What moved things on from routine fare like ”That’s Alright” and “Rockin’ Daddy” was in part the quality of his sidemen. The young Hubert Sumlin, (who died December 4th 2011) summoned from Memphis, quickly developed the piercing riffs and curlicued solos that became a signature of Wolf’s later output (try “I’m Leaving”), and which made him a hero to the likes of Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck. Chess sessioneers included outstanding players like pianists Otis Spann and Hosea Lee Kennard – the latter’s hammering keyboard elevates the second half of this collection – while bassist Willie Dixon was a prize songwriter and arranger. Another relocated southerner, Dixon had supplied Wolf with “Evil” before a fall-out with the Chess brothers over money. When he returned he hit a dazzling streak that included “Wang Dang Doodle”, “ Back Door Man” and “Spoonful” – a trinity that closes this compilation – and later “Little Red Rooster” and “I Ain’t Superstitious” among others.

Discs three and four, with their flurries of out-takes and studio banter, give a pungent taste of how these masterpieces were created; with a mixture of tiresome persistence, exceptional skill and pure love for a music that was so often about being unloved.

Neil Spencer