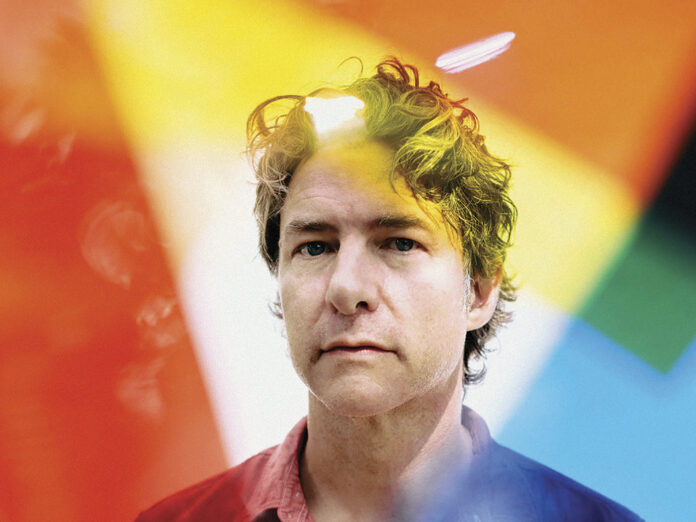

“I've always been more interested in sketches than finished paintings,” says James Elkington. “I like listening to people's demos. I'm very interested in unfinished work, or work-in-progress. And I wanted this to sound like that.” Me Neither isn’t Elkington’s official follow-up to 2020’s excellent Ever-Roving Eye (that’s coming next year, along with a duo album he’s made with Nathan Salsburg). In fact he only finished this batch of recordings in September, and wasn’t planning to release them formally until No Quarter’s Mike Quinn intervened. “I haven't even had a chance to think about whether it's a good idea to put it out,” Elkington admits. “That's partly why it's called Me Neither. I'm not sure exactly what my involvement level is with this, really.”

“I’ve always been more interested in sketches than finished paintings,” says James Elkington. “I like listening to people’s demos. I’m very interested in unfinished work, or work-in-progress. And I wanted this to sound like that.” Me Neither isn’t Elkington’s official follow-up to 2020’s excellent Ever-Roving Eye (that’s coming next year, along with a duo album he’s made with Nathan Salsburg). In fact he only finished this batch of recordings in September, and wasn’t planning to release them formally until No Quarter’s Mike Quinn intervened. “I haven’t even had a chance to think about whether it’s a good idea to put it out,” Elkington admits. “That’s partly why it’s called Me Neither. I’m not sure exactly what my involvement level is with this, really.”

KEITH RICHARDS IS ON THE COVER OF THE NEW UNCUT – HAVE A COPY SENT STRAIGHT TO YOUR HOME

It’s not quite a feat of subconscious composition to rank alongside <Astral Weeks> – you suspect that Elkington’s solid, curatorial nous was more present in the construction of this music than he’s letting on – but Me Neither is certainly a cabinet of curiosities: 28 spry instrumental vignettes, plus a not-quite cover of Abba’s “The Winner Takes It All”.

Almost everything is played on acoustic guitar, but Elkington uses the instrument inventively, tapping it with felt mallets to create a percussion track or elongating notes with a freeze pedal until they begin to sound like synth tones. There are some lo-fi tape loops, plus found sounds that include the recording of a train going past his house. Even the straighter folk fingerpicking numbers are spontaneous attempts to explore a new tuning or a curious time signature, and yet Elkington always seems to come up with something pleasing and melodic. He’s freed himself from the constraints of trying to write complete songs, but this isn’t aimless experimentation. At roughly two minutes apiece, these little sketches are the opposite of improvised indulgence.

Halfway through, Elkington wondered if he might be making an album of library music for potential film and TV use. It would be quite a modish thing to do, given that the likes of Ben Chasny and Matt Berry have recently released instrumental albums under the reactivated KPM banner. “But then I sent it to a friend who actually does library music placement,” reveals Elkington, “and he was like, ‘I don’t think so!’”

He should probably take that snub as a compliment. Most of these tunes are too characterful to be used as general scene-setting; “The 100-Faced Magma” and “Part The Thin Painter From His Work” – Elkington presumably had as much fun titling them as writing them – have a jolly, perambulatory quality, as if accompanying a cast of local eccentrics as they wend their way to work through the streets of a pretty Alpine village. Others, such as “A Round, A Bout” and the beautiful “Double Orchid”, are odder and more atmospheric. Thankfully, they all lack the pretentious/portentous widescreen sweep of most present-day soundtrack (or ‘imaginary soundtrack’) music. Whatever kind of production this might be for, it’s a resolutely small-screen one: a children’s stop-motion animation or a nature documentary, viewed at 11am on a chilly Monday while stuck at home with a cold.

Growing up in England in the 1970s, there’s no doubt that Elkington’s first encounter with instrumental folk guitar music will have been via Camberwick Green and Bagpuss rather than Bert Jansch and John Fahey. Me Neither acknowledges this formative influence without getting too cutesy about it. In that sense – not to mention his homespun Radiophonic Workshop-style FX and the way his guitar is often warped and woozed by several generations of tape dubs – you can draw comparisons with Broadcast and Boards Of Canada. This album shares their complex, peculiarly British relationship with nostalgia: fuzzy and comforting but potentially sinister around the edges.

In conclusion, it would be traditional to observe that Me Neither bodes well for both of Elkington’s ‘proper’ albums coming next year. Which it does, of course – after a couple of decades as a supporting player on the Chicago scene, he seems to be coming into his own as a leading man. But you don’t need any of that context to enjoy Me Neither and its random sprinkling of everyday wonder.