“Electric Church” was one of the notional post-Experience formulations (see also: Gypsy, Sun and Rainbows) that Jimi Hendrix imagined for his music after the demise of the original Jimi Hendrix Experience. In truth, his grander ideas of musical freedom went chiefly undeveloped as the artist was kept on the road, shackled to something like a version of his original trio.

In such a context, Hendrix’s engagement at the second Atlanta Pop Festival on July 4, 1970 initially feels as if it may be unpromising material from which to draw a live album and documentary. Sure enough, the film bears the resoundingly shonky imprimatur of the Experience Hendrix organization: directed by collector/archivist John McDermott and beginning with an unintentionally psychedelic appraisal of Hendrix’s genius from persons living and dead, all presented with no context or attribution whatever.

However, from then on, the film shows its working in a rather more candid and satisfactory way. In 1970, Steve Rash (who went on to direct The Buddy Holly Story) shot Atlanta Pop, but never processed his material until he began working on his own documentary about it a few years ago. Thanks largely to Rash’s footage, this film now accesses something like an unheard Hendrix story.

Byron, Georgia (actually 100 miles outside Atlanta) was not a place where African-Americans like Jimi Hendrix had historically had reason to feel welcome. A representative local citizen of the period was a man named Lester Maddox, owner of a restaurant called The Pickrick, which he vowed to keep segregated by any means he could. By the time of Hendrix’s visit to the state, Maddox was governor.

It’s clearly the intention of Electric Church to develop the idea of Hendrix as Jesse Owens in a deep south version of the 1936 Olympics – his performance a triumph against malign ideology. Appealing as that notion may be as footage of Maddox stacks up, the film is at its freshest with material it generates itself.

Via present-day interviews with promoter Mike Cooley, musicians who played and particularly with Byron residents who remember the event, what emerges is an extremely entertaining picture of a region utterly bemused by a long-haired, pot-smoking, often unclothed counterculture, that it had never before witnessed. In so doing, what began as padding to performance footage becomes a more subtle portrait of commerce and moral outrage then anyone might have expected.

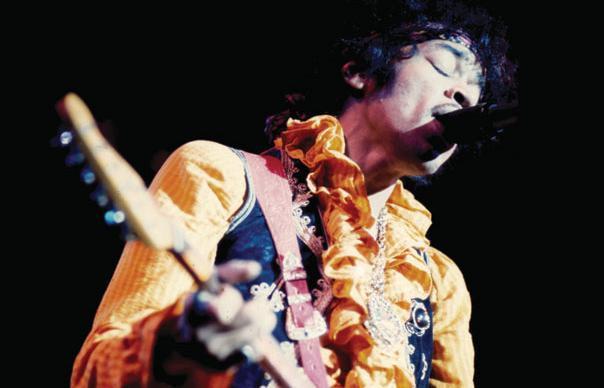

Though near death, in performance Hendrix himself, meanwhile, is very much alive. The versions of “All Along The Watchtower”, “Purple Haze” and “Stone Free” in particular find new paths through familiar terrain. It’s revealing also of Hendrix’s sensitivity to his band’s limitations – while Mitch Mitchell could be as freewheeling as the guitarist, the more doughty Billy Cox couldn’t hope to follow him – rendering the performance improvisational but never distractingly digressive. Here, on the tightrope between pop and searching experiment, was where Hendrix was at his most thrilling.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.