Nominated for two Grammy awards in 1965, John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme was beaten by Ramsey Lewis’ The In Crowd for best jazz performance by a small group and by Paul Horn and Lalo Schifrin’s Jazz Suite On The Mass Texts for best original jazz composition. Half a century later, it is one of the two modern jazz albums most likely to be present in the collections of people who possess only two modern jazz albums.

Like the other candidate for that distinction, Miles Davis’ Kind Of Blue, it seemed to have sprung fully grown from the imagination of its creator, apparently requiring neither rehearsal nor revision. The amount of ancillary material – the equivalent of preliminary sketches and offcuts – is therefore minimal. This has made it hard for producers to construct the enhanced versions devised as a lure to get people who acquired it the first time to buy it all over again, particularly when an anniversary, such as A Love Supreme’s golden jubilee, is spotted by the marketing department.

The first expanded version of Coltrane’s masterpiece appeared in 2002, as part of Universal’s Deluxe Edition series. Alongside the original 33-minute quartet recording, for which Coltrane was joined in Rudy Van Gelder’s New Jersey studio by his regular lineup of McCoy Tyner (piano), Jimmy Garrison (bass) and Elvin Jones (drums), it contained a second disc including the only live performance of the suite, recorded by the same personnel at the Antibes Jazz Festival in July 1965, shortly after the album’s release in the United States. The remaining bonus tracks were two outtakes of “Resolution”, the suite’s second movement, by the quartet, and two of “Acknowledgement”, its opening movement, by an expanded version of the group, with the young tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp and the veteran bassist Art Davis added to the lineup.

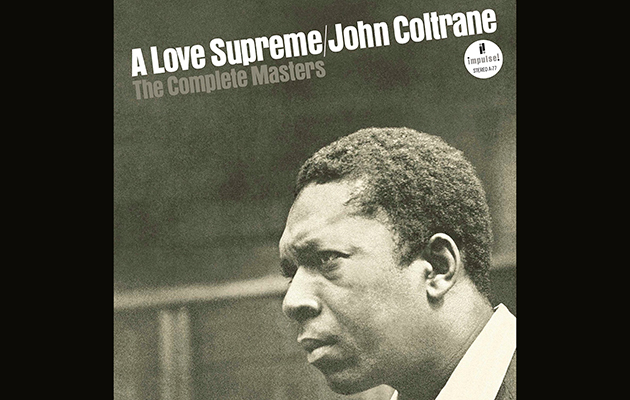

This new edition – curated by Ashley Kahn, the author of a fine book about the album published by Granta a few years ago, and Harry Weinger, the genius behind Hip-O Select’s peerless Motown compilations – comes in two sizes. A two-disc version contains the original album, plus seven outtakes from the quartet and sextet sessions, and two mono “reference” versions of the finished third and fourth movements, “Pursuance” and “Peace”, which were given to Coltrane by his producer, Bob Thiele, to take home from the session. The three-disc “Super Deluxe Edition” adds the Antibes concert and extra sleeve notes relating to the live performance.

Fellow fanatics will be interested to hear, from the mono reference tape, the brief double-stopped figure with which Garrison ends “Psalm” (excised from the finished master), and the version of the same piece before Coltrane overdubbed a few notes on alto saxophone to the coda. His original scheme for the suite apparently involved a much larger group, with two basses, and three percussionists (two on congas plus one timbalero); the half-dozen takes of the sextet version of “Acknowledgement” hint at why the attempt at expansion failed, although the idea was only temporarily abandoned and would return with further large-scale works, Ascension and Meditations, the following year.

The Antibes set gives us a looser, less solemn but still mesmerising version of the whole piece, including a version of “Pursuance” that finds Coltrane stretching out in the mode of his great 1961 live recording “Chasin’ The Trane”, oblivious to everything but the pursuit of nirvana in the company of Jones’ tireless drumming. At no time was A Love Supreme in Coltrane’s live repertoire; he had agreed to play the composition, Kahn tells us, in response to a request from the French jazz composer Jef Gilson, who had heard an advance copy of the album.

The booklet accompanying this latest reissue contains hitherto unseen session photographs, facsimiles of the relevant pages from Van Gelder’s diary, Coltrane’s early blueprint for the score and his handwritten notes, including the prayer intended to provide an accompanying text to the music. These jottings really do draw us closer to the great man at the very peak of his career, when he was funneling his increasingly urgent spiritual concerns through the medium of the instrumental skills he had spent 20 years perfecting with something close to obsession. We can now see that alongside an exhortation to “Keep your eye on God” he scrawled another aide-memoire: “Buy reeds in S.F.”.

No-one should purchase either of these sets expecting fresh revelations. In neither of its formats does A Love Supreme: The Complete Masters significantly increase an understanding of either the inspiration or the methodology behind a work best absorbed by the newcomer via the form in which Coltrane chose to give it to us. But in whatever format, the work retains all the power that led Patti Smith to describe it as possessing “the feeling of moral authority in the most humble and spiritual way”. On its arrival in 1965, at a time when Coltrane’s music had so often appeared to mirror the dark turbulence of world affairs, its perfect combination of intensity and clarity made it stand out from everything around it. In 50 years, not much has changed.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.