In late 2006 I interviewed John Martyn in the beer garden of his local in Thomastown, Kilkenny. In between bombing pints of cider laced with vodka and demolishing a cheese and onion toastie in three mouthfuls, he told me the follow-up to his 2004 album, On The Cobbles, was almost done. Perhaps it was, but at the time of his premature death from pneumonia in January 2009 it still hadn’t appeared. Finally, here it is. Apparently completed just before he died and released without any posthumous tinkering, it’s almost impossible to prevent hindsight from partially hijacking our expectations. Perhaps many of us hoped Martyn’s last recordings would take the form of a hushed, elegiac final reckoning, forgetting that these nine songs were never intended to carry that weight. Instead we get something very different. Flawed, undeniably, but rudely, robustly alive. At times On The Cobbles returned to within an ace of Martyn’s best work. Heaven And Earth isn’t so obviously beguiling. Mostly recorded at Martyn’s home in Thomastown, the textures are less organic, the songs looser and happier to embark on extended workouts. There is some evidence that these final recordings were created in extremis. Always a tippler and toker extraordinaire, having lost a leg to septicaemia in 2003 Martyn entered his final years in a state of advanced disrepair. While it’s great to hear that inimitable voice one more time, there’s no denying it had seen better days; for much of this record he sounds like Barry White nursing a bad grudge and a 30-year hangover. In short, Heaven And Earth is more “Big Muff” than “May You Never”, with perhaps a hint of “Johnny Too Bad” around the edges. Several songs are defined by a kind of thick, slow funk, ambling forward on great slabs of rhythm. When it works it’s a fine sound. “Stand Amazed” is a spare, sinewy, swampy skank stretching out over seven delicious minutes, the spaces fleshed out by a wall of girl singers. Caught between blues and funk, “Bad Company” and “Heel Of The Hunt” are similarly steamy affairs which rumble and roll without ever quite producing a lightning bolt. “Gambler” is far more convincing, with its rattling drums, boogie piano, organ swirls and badass bass. It’s taut and vaguely dangerous, filled with late night menace. The remaining tracks lean towards a more ragged approximation of the slick, slinky sound which characterised many of Martyn’s ’80s albums. The title track is all tinkling piano, burbling bass and a lightly vocoded vocal which turns every vowel into a cosmic gargle. Despite the ripe entertainment of hearing this salty pirate making like some melismatic R&B siren, the end result is less “Solid Air” and more cocktail hour. Much better is “Could’ve Told You Before I Met You”, an uplifting piece of shimmering pop with a zinging chorus. Once again Martyn’s voice is heavily treated, giving his honey-and-gravel tones even more of a woozy, narcotic edge. Where Paul Weller and Mavis Staples guested on On The Cobbles, this time Garth Hudson and Martyn’s old friend, Phil Collins, provide celebrity cameos. Hudson adds lovely drunken accordion to “Stand Amazed”, but it’s Collins’ “Can’t Turn Back The Years” – the only non-Martyn original here, on which the ex-Genesis man also contributes backing vocals and keyboards – that is the real highlight. If it doesn’t quite scale the peaks of the pair’s previous collaborations on Grace And Danger, it’s not far short, a seductive, carefully calibrated ballad which features the best Martyn vocal on the album. “Colour” has a fine bluesy riff running through it but veers towards the anonymous, while the closing “Willing To Work” – “woop-de-doos”, barking dogs and all – is little more than an extended jam which hardly justifies its eight minutes. When Martyn growls “give me a name and I’ll live up to it” it’s partly bottled bravado, but it also reveals a genuine desire to stay within touching distance of his greatness. There’s little on Heaven And Earth to truly trouble his best work, but throughout there’s plentiful evidence of the many qualities which made Martyn so indefinable and influential. And, lest we forget, utterly irreplaceable. Graeme Thomson

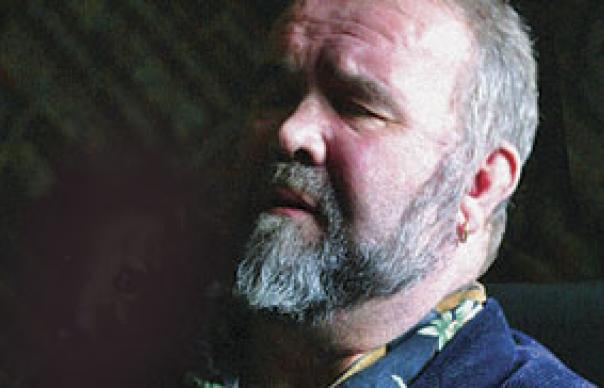

In late 2006 I interviewed John Martyn in the beer garden of his local in Thomastown, Kilkenny. In between bombing pints of cider laced with vodka and demolishing a cheese and onion toastie in three mouthfuls, he told me the follow-up to his 2004 album, On The Cobbles, was almost done. Perhaps it was, but at the time of his premature death from pneumonia in January 2009 it still hadn’t appeared.

Finally, here it is. Apparently completed just before he died and released without any posthumous tinkering, it’s almost impossible to prevent hindsight from partially hijacking our expectations. Perhaps many of us hoped Martyn’s last recordings would take the form of a hushed, elegiac final reckoning, forgetting that these nine songs were never intended to carry that weight. Instead we get something very different. Flawed, undeniably, but rudely, robustly alive.

At times On The Cobbles returned to within an ace of Martyn’s best work. Heaven And Earth isn’t so obviously beguiling. Mostly recorded at Martyn’s home in Thomastown, the textures are less organic, the songs looser and happier to embark on extended workouts. There is some evidence that these final recordings were created in extremis. Always a tippler and toker extraordinaire, having lost a leg to septicaemia in 2003 Martyn entered his final years in a state of advanced disrepair. While it’s great to hear that inimitable voice one more time, there’s no denying it had seen better days; for much of this record he sounds like Barry White nursing a bad grudge and a 30-year hangover.

In short, Heaven And Earth is more “Big Muff” than “May You Never”, with perhaps a hint of “Johnny Too Bad” around the edges. Several songs are defined by a kind of thick, slow funk, ambling forward on great slabs of rhythm. When it works it’s a fine sound. “Stand Amazed” is a spare, sinewy, swampy skank stretching out over seven delicious minutes, the spaces fleshed out by a wall of girl singers. Caught between blues and funk, “Bad Company” and “Heel Of The Hunt” are similarly steamy affairs which rumble and roll without ever quite producing a lightning bolt. “Gambler” is far more convincing, with its rattling drums, boogie piano, organ swirls and badass bass. It’s taut and vaguely dangerous, filled with late night menace.

The remaining tracks lean towards a more ragged approximation of the slick, slinky sound which characterised many of Martyn’s ’80s albums. The title track is all tinkling piano, burbling bass and a lightly vocoded vocal which turns every vowel into a cosmic gargle. Despite the ripe entertainment of hearing this salty pirate making like some melismatic R&B siren, the end result is less “Solid Air” and more cocktail hour. Much better is “Could’ve Told You Before I Met You”, an uplifting piece of shimmering pop with a zinging chorus. Once again Martyn’s voice is heavily treated, giving his honey-and-gravel tones even more of a woozy, narcotic edge.

Where Paul Weller and Mavis Staples guested on On The Cobbles, this time Garth Hudson and Martyn’s old friend, Phil Collins, provide celebrity cameos. Hudson adds lovely drunken accordion to “Stand Amazed”, but it’s Collins’ “Can’t Turn Back The Years” – the only non-Martyn original here, on which the ex-Genesis man also contributes backing vocals and keyboards – that is the real highlight. If it doesn’t quite scale the peaks of the pair’s previous collaborations on Grace And Danger, it’s not far short, a seductive, carefully calibrated ballad which features the best Martyn vocal on the album.

“Colour” has a fine bluesy riff running through it but veers towards the anonymous, while the closing “Willing To Work” – “woop-de-doos”, barking dogs and all – is little more than an extended jam which hardly justifies its eight minutes. When Martyn growls “give me a name and I’ll live up to it” it’s partly bottled bravado, but it also reveals a genuine desire to stay within touching distance of his greatness. There’s little on Heaven And Earth to truly trouble his best work, but throughout there’s plentiful evidence of the many qualities which made Martyn so indefinable and influential. And, lest we forget, utterly irreplaceable.

Graeme Thomson