Old and new treasures from the folk pioneer... “The roof can leak all it likes if you live in the basement, know what I mean?” says John Martyn, introducing “Bless The Weather”, in a voice like Neil from The Young Ones, to a crowd at a Richmond folk club in 1972. Although dropped casually and with typically endearing wit, it’s loaded, in retrospect, with significance considering the state his life was in. Holed up in a rambling new house in the unsettling seaside town of Hastings with wife Beverley, who had had to endure being compared to the decapitating Salome in his song “John The Baptist”, and who was now essentially sacrificing her own promising career to look after her own and John’s children, he was busy running life ragged. Even as this twinkle-eyed roving minstrel could sing songs like “May You Never” and “Back To Stay” about his undying marital fidelity, he was sleeping with Island labelmate Claire Hamill, whose records he had produced and who accompanied him on tour. His free spirit was both gorgeously attractive, and fatally destructive: he remained chirpy even as the attic floorboards were rotting away. But we’ve all been content to let John Martyn off the hook, because of the sheer vitality and beauty of so much of his music. And a box set like this one – following Island’s comprehensive Sandy Denny monolith from 2010 – is a completist’s dream. It contains every Island LP from London Conversation (1967) to The Apprentice (recorded for Island in 1987 but issued three years later in a different version on Permanent), each with never-on-CD extras polished up and tacked on. There are four standalone discs of live recordings or outtakes spanning the same period, again unreleased (including the fine, complete set from Richmond Hanging Lamp, and an entire CD of newly discovered One World discards). There’s also a DVD featuring Martyn on stage and TV, including the complete Foundations concert from 1986, plus the inevitable hardback book with notes by compiler and JohnMartyn.com website host John Hillarby. Four years after his death, Martyn’s life work comes to seem like a philanderer’s testimony, a bipolar misogynist’s covering of his own tracks. What and who was this roving minstrel, a half-English, half-Scotsman who ended up living in Ireland with one leg? He could be charming, erudite, laddish, demented. An uncontrollable alcoholic and adulterer, a charitable philanthropist unafraid of a scrap (he once beat up a heckling Sid Vicious). The contradictions are ever present in performance. Look at the Old Grey Whistle Test footage, some of the best of its kind, of him performing “Make No Mistake” in 1973 – his utter immersion in the song’s passion, tenderness, the yearning coupled with stupendous guitar technique. For those brief minutes while he is inside it, music seems like a refuge from all the world’s ugliness and cynicism. And then between numbers, the pisstaking oaf returns. Age was not kind to John Martyn, metamorphosing him from a merman to a grizzly bear. In his first professional decade he reached down into his own cherubic voice and discovered a devil lurking there. The slurring and roaring on Inside Out (1973) and One World (1977) become, by Sapphire (1984) and Piece By Piece (1986), a raucous, unsavoury bellow. Grace And Danger (1980) – supplied here with a whole extra disc of outtakes and live airshots from the period – remains an appealing tipping point, songs like “Some People Are Crazy” and “Hurt In Your Heart” representing articulate interventions against his own demonic impulses. The Island Years also throws out hints of the more experimental paths Martyn might have trodden. By 1977, captured here in a so-far unheard gig from Sydney, he’s opening sets with the massive echoplex outback of “Outside In”, stretching to a tumultuous 16 minutes. As well as the magnificent testosterone sprawl of Live At Leeds – practically an onstage musical brawl between Martyn, Danny Thompson and Improv drummer John Stevens – and the pearly amniotic folds of “Small Hours”, Hillarby includes the very rare “Anni Parts 1 & 2” by John Stevens’s Away, a funk-driven outfit which Martyn briefly joined after the singer’s notorious 1975 tour. Released as a Vertigo 7” in 1976, it’s stunning to hear it in CD quality for the first time, and it goes a long way to explaining the electronics and slouchy grooves of the following year’s One World. It’s the original UK mix of One World that’s included here – apparently the American edition was given different emphasis, though it’s impossible to compare now. It still sounds fresh minted, bearing traces of Martyn’s recent, colourful sojourn in Jamaica (“Big Muff” was inspired by a lewd comment Lee Perry made about Chris Blackwell’s breakfast china). The dark places Martyn had visited make themselves known in “Dealer” and “Smiling Stranger”, but there’s profound joy here too (“Couldn’t Love You More”), and an aquatic post-rock ambience on “Certain Surprise”, “Dancing” and the title track that no one has quite equalled since. “Small Hours”, recorded in pre-dawn light by a lake in the grounds of Blackwell’s Berkshire farmstead, is what New Age music always should have been: an impassioned, starsailing voyage into the ether, with the air so still you can hear distant trains and geese migrating overhead. Bless The Weather (1971) and Solid Air (1973) feel so canonical by now that there’s little more to be said except that they are included, along with work-in-progress studio takes and guide tracks that are substantially revealing about the fluidity and spontaneity of Martyn’s methods. Sunday’s Child, from 1975, is often overlooked, but it too contains some of Martyn’s tenderest ballads (“You Can Discover”, “My Baby Girl”) and the tropical funk he could stew up from a few amplified ingredients, given the right combination of musicians (“Root Love”, “Clutches”). You may well own these already, but the value of this collection is as a portrait of the artist through time, and a compilation of the irresistible outpourings of a man who never really knew who he was. Rob Young Q&A Compiler John Hillarby of johnmartyn.com Did you find everything you hoped for in compiling the set? Were there any big surprises? Research always starts with tape reports produced by the Island Records Tape Archive Facility. Some of the information on the tapes is good and others less so, and it’s often the case that a reel to reel tape that has five songs listed as being on it has more, and unfortunately sometimes the opposite! Many of the song titles written on the tape boxes are working titles and bear no relevance to what is actually on the tape, so it’s always an interesting journey. I was hoping to find some sessions John recorded with [South African free jazz saxophonist] Dudu Pukwana, but they didn’t come to light. I suspect they may be incorrectly labelled in the archive – if they are there at all. You have to do some lateral thinking because, for example, much of the stuff John recorded with [ex-Free guitarist] Paul Kossoff is filed under Kossoff, and if you don’t understand things like that you can miss things. Finding the unreleased songs was a great buzz. There can be the most sublime take, and then in true John style he bursts out laughing, or cracks a joke or asks for a spliff. Panning for the gold of a great unheard song or take or mix is a real buzz... but can be frustrating. What comes over is how naturally music came to John, his sense of fun and, more than anything else, the sheer scope and panorama of this stunning body of work he left us, from acoustic folk to jazz to rock to blues to Eastern textures to rock to pop to 80s synthesizers – he was progressive in the true sense of the word. Any gems that you couldn’t include on the set due to space or other reasons? Inevitably, but almost all of the really interesting material is in the box. Several times we found something that really had to be included, and that meant something else got bumped. That’s always an incredibly tough decision. For example, the USA mix of One World was bumped in favour of the album outtakes. We always try to use unreleased material. Early good quality live recordings are very rare, so the Hanging Lamp concert from 1972 is very special. There is a huge quantity of live recordings that could have been drawn on, but a lot of it, although musically fantastic, is 70s amateur recordings, and a bit too rough for a prestige box set like this. John tinkered with an experimental/jazz/fusion-type direction, but ended up instead with the AOR orientated material of the post-Grace and Danger era. Why do you think that was? John was always influenced by jazz and I’ve always felt that “So Much In Love With You” from Inside Out is a great example. “Anni” (by John Stevens Away) is a fantastic song, and there are definite jazz elements in the Live At Leeds trio. John had enormous admiration for John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders but he didn’t have a jazz background. He did try to play saxophone when he was younger but didn't take to it – thankfully! I don’t think John was ever AOR, he was too honest a songwriter. Much of John’s music has an edge: he didn’t like a ‘straight’ sound or note; he preferred to bend or distort it. I think that edge, and the Celtic notes of sadness and despair, would just never be smooth enough for that genre. For many, John's late 60s/early to mid-70s music will be thought of as his golden age. Is there any reason to re-evaluate the 1980s years? Absolutely. John got bored easily and always looked to change his sound and move forward, and most of the time was way ahead of everyone. Something like his 1981 album Glorious Fool has a different sound, but the vocals, guitar and song writing are first class and stand every inch with his 70s work. The same with Sapphire and Piece By Piece. He was always evolving, looking for something fresh, and some of it worked better than others, as with any artist whose career spans 40 plus years. “John Wayne”, “Fisherman’s Dream” and “Mad Dog Days” are outstanding tracks, all from the end of the Island era. Those who expected John’s music to stay as it was in the 1970s totally failed to understand him. John lived for the moment, lived life to the full and experimenting and exploring was part of his being. Those who only listen to John’s 1970s output are missing out on a lot of great music! What is the archetypal John Martyn track? For exploration, experimentation and pushing back the boundaries it would have to be “Outside In”, probably the version from Live At Leeds or the BBC Sight And Sound In Concert version, which is released in this box set for the first time. For sensitivity and John’s unique insight on the world, I would choose “One World”. It is both innocent and all-knowing at the same time. Yesterday I was at the Environmental Fair in Carshalton Park and there was a handpainted banner by the solar powered stage that simply said, “One World”. The phrase is commonplace nowadays, but wasn’t in 1977. John would have roared with laughter and said, “Fucking took ’em long enough”. INTERVIEW: ROB YOUNG

Old and new treasures from the folk pioneer…

“The roof can leak all it likes if you live in the basement, know what I mean?” says John Martyn, introducing “Bless The Weather”, in a voice like Neil from The Young Ones, to a crowd at a Richmond folk club in 1972. Although dropped casually and with typically endearing wit, it’s loaded, in retrospect, with significance considering the state his life was in. Holed up in a rambling new house in the unsettling seaside town of Hastings with wife Beverley, who had had to endure being compared to the decapitating Salome in his song “John The Baptist”, and who was now essentially sacrificing her own promising career to look after her own and John’s children, he was busy running life ragged.

Even as this twinkle-eyed roving minstrel could sing songs like “May You Never” and “Back To Stay” about his undying marital fidelity, he was sleeping with Island labelmate Claire Hamill, whose records he had produced and who accompanied him on tour. His free spirit was both gorgeously attractive, and fatally destructive: he remained chirpy even as the attic floorboards were rotting away.

But we’ve all been content to let John Martyn off the hook, because of the sheer vitality and beauty of so much of his music. And a box set like this one – following Island’s comprehensive Sandy Denny monolith from 2010 – is a completist’s dream. It contains every Island LP from London Conversation (1967) to The Apprentice (recorded for Island in 1987 but issued three years later in a different version on Permanent), each with never-on-CD extras polished up and tacked on. There are four standalone discs of live recordings or outtakes spanning the same period, again unreleased (including the fine, complete set from Richmond Hanging Lamp, and an entire CD of newly discovered One World discards). There’s also a DVD featuring Martyn on stage and TV, including the complete Foundations concert from 1986, plus the inevitable hardback book with notes by compiler and JohnMartyn.com website host John Hillarby.

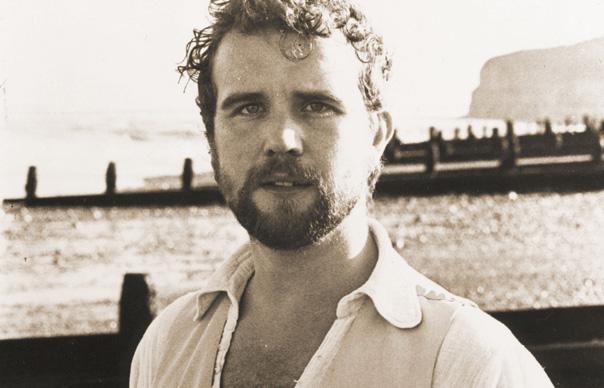

Four years after his death, Martyn’s life work comes to seem like a philanderer’s testimony, a bipolar misogynist’s covering of his own tracks. What and who was this roving minstrel, a half-English, half-Scotsman who ended up living in Ireland with one leg? He could be charming, erudite, laddish, demented. An uncontrollable alcoholic and adulterer, a charitable philanthropist unafraid of a scrap (he once beat up a heckling Sid Vicious). The contradictions are ever present in performance. Look at the Old Grey Whistle Test footage, some of the best of its kind, of him performing “Make No Mistake” in 1973 – his utter immersion in the song’s passion, tenderness, the yearning coupled with stupendous guitar technique. For those brief minutes while he is inside it, music seems like a refuge from all the world’s ugliness and cynicism. And then between numbers, the pisstaking oaf returns.

Age was not kind to John Martyn, metamorphosing him from a merman to a grizzly bear. In his first professional decade he reached down into his own cherubic voice and discovered a devil lurking there. The slurring and roaring on Inside Out (1973) and One World (1977) become, by Sapphire (1984) and Piece By Piece (1986), a raucous, unsavoury bellow. Grace And Danger (1980) – supplied here with a whole extra disc of outtakes and live airshots from the period – remains an appealing tipping point, songs like “Some People Are Crazy” and “Hurt In Your Heart” representing articulate interventions against his own demonic impulses.

The Island Years also throws out hints of the more experimental paths Martyn might have trodden. By 1977, captured here in a so-far unheard gig from Sydney, he’s opening sets with the massive echoplex outback of “Outside In”, stretching to a tumultuous 16 minutes. As well as the magnificent testosterone sprawl of Live At Leeds – practically an onstage musical brawl between Martyn, Danny Thompson and Improv drummer John Stevens – and the pearly amniotic folds of “Small Hours”, Hillarby includes the very rare “Anni Parts 1 & 2” by John Stevens’s Away, a funk-driven outfit which Martyn briefly joined after the singer’s notorious 1975 tour. Released as a Vertigo 7” in 1976, it’s stunning to hear it in CD quality for the first time, and it goes a long way to explaining the electronics and slouchy grooves of the following year’s One World.

It’s the original UK mix of One World that’s included here – apparently the American edition was given different emphasis, though it’s impossible to compare now. It still sounds fresh minted, bearing traces of Martyn’s recent, colourful sojourn in Jamaica (“Big Muff” was inspired by a lewd comment Lee Perry made about Chris Blackwell’s breakfast china). The dark places Martyn had visited make themselves known in “Dealer” and “Smiling Stranger”, but there’s profound joy here too (“Couldn’t Love You More”), and an aquatic post-rock ambience on “Certain Surprise”, “Dancing” and the title track that no one has quite equalled since. “Small Hours”, recorded in pre-dawn light by a lake in the grounds of Blackwell’s Berkshire farmstead, is what New Age music always should have been: an impassioned, starsailing voyage into the ether, with the air so still you can hear distant trains and geese migrating overhead.

Bless The Weather (1971) and Solid Air (1973) feel so canonical by now that there’s little more to be said except that they are included, along with work-in-progress studio takes and guide tracks that are substantially revealing about the fluidity and spontaneity of Martyn’s methods. Sunday’s Child, from 1975, is often overlooked, but it too contains some of Martyn’s tenderest ballads (“You Can Discover”, “My Baby Girl”) and the tropical funk he could stew up from a few amplified ingredients, given the right combination of musicians (“Root Love”, “Clutches”). You may well own these already, but the value of this collection is as a portrait of the artist through time, and a compilation of the irresistible outpourings of a man who never really knew who he was.

Rob Young

Q&A

Compiler John Hillarby of johnmartyn.com

Did you find everything you hoped for in compiling the set? Were there any big surprises?

Research always starts with tape reports produced by the Island Records Tape Archive Facility. Some of the information on the tapes is good and others less so, and it’s often the case that a reel to reel tape that has five songs listed as being on it has more, and unfortunately sometimes the opposite! Many of the song titles written on the tape boxes are working titles and bear no relevance to what is actually on the tape, so it’s always an interesting journey.

I was hoping to find some sessions John recorded with [South African free jazz saxophonist] Dudu Pukwana, but they didn’t come to light. I suspect they may be incorrectly labelled in the archive – if they are there at all. You have to do some lateral thinking because, for example, much of the stuff John recorded with [ex-Free guitarist] Paul Kossoff is filed under Kossoff, and if you don’t understand things like that you can miss things. Finding the unreleased songs was a great buzz. There can be the most sublime take, and then in true John style he bursts out laughing, or cracks a joke or asks for a spliff. Panning for the gold of a great unheard song or take or mix is a real buzz… but can be frustrating. What comes over is how naturally music came to John, his sense of fun and, more than anything else, the sheer scope and panorama of this stunning body of work he left us, from acoustic folk to jazz to rock to blues to Eastern textures to rock to pop to 80s synthesizers – he was progressive in the true sense of the word.

Any gems that you couldn’t include on the set due to space or other reasons?

Inevitably, but almost all of the really interesting material is in the box. Several times we found something that really had to be included, and that meant something else got bumped. That’s always an incredibly tough decision. For example, the USA mix of One World was bumped in favour of the album outtakes. We always try to use unreleased material. Early good quality live recordings are very rare, so the Hanging Lamp concert from 1972 is very special. There is a huge quantity of live recordings that could have been drawn on, but a lot of it, although musically fantastic, is 70s amateur recordings, and a bit too rough for a prestige box set like this.

John tinkered with an experimental/jazz/fusion-type direction, but ended up instead with the AOR orientated material of the post-Grace and Danger era. Why do you think that was?

John was always influenced by jazz and I’ve always felt that “So Much In Love With You” from Inside Out is a great example. “Anni” (by John Stevens Away) is a fantastic song, and there are definite jazz elements in the Live At Leeds trio. John had enormous admiration for John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders but he didn’t have a jazz background. He did try to play saxophone when he was younger but didn’t take to it – thankfully!

I don’t think John was ever AOR, he was too honest a songwriter. Much of John’s music has an edge: he didn’t like a ‘straight’ sound or note; he preferred to bend or distort it. I think that edge, and the Celtic notes of sadness and despair, would just never be smooth enough for that genre.

For many, John’s late 60s/early to mid-70s music will be thought of as his golden age. Is there any reason to re-evaluate the 1980s years?

Absolutely. John got bored easily and always looked to change his sound and move forward, and most of the time was way ahead of everyone. Something like his 1981 album Glorious Fool has a different sound, but the vocals, guitar and song writing are first class and stand every inch with his 70s work. The same with Sapphire and Piece By Piece. He was always evolving, looking for something fresh, and some of it worked better than others, as with any artist whose career spans 40 plus years. “John Wayne”, “Fisherman’s Dream” and “Mad Dog Days” are outstanding tracks, all from the end of the Island era. Those who expected John’s music to stay as it was in the 1970s totally failed to understand him. John lived for the moment, lived life to the full and experimenting and exploring was part of his being. Those who only listen to John’s 1970s output are missing out on a lot of great music!

What is the archetypal John Martyn track?

For exploration, experimentation and pushing back the boundaries it would have to be “Outside In”, probably the version from Live At Leeds or the BBC Sight And Sound In Concert version, which is released in this box set for the first time. For sensitivity and John’s unique insight on the world, I would choose “One World”. It is both innocent and all-knowing at the same time. Yesterday I was at the Environmental Fair in Carshalton Park and there was a handpainted banner by the solar powered stage that simply said, “One World”. The phrase is commonplace nowadays, but wasn’t in 1977. John would have roared with laughter and said, “Fucking took ’em long enough”.

INTERVIEW: ROB YOUNG