John Lennon knew exactly what he was doing. He was going to make an album that would establish him as a fully fledged solo act, one to prove that going primal on Plastic Ono Band and becoming a “conceptual artist” like Yoko didn’t mean he’d lost his touch as a mainstream hitmaker. He’d alr...

John Lennon knew exactly what he was doing. He was going to make an album that would establish him as a fully fledged solo act, one to prove that going primal on Plastic Ono Band and becoming a “conceptual artist” like Yoko didn’t mean he’d lost his touch as a mainstream hitmaker. He’d already written the songs.

The album would be made at home in Tittenhurst Park, his and Yoko’s Ascot pile, using its recently completed home studio. And it would be filmed, all of it, both the recording sessions and John’n’Yoko’s life together. Among the resultant footage was the shoot for “Imagine”, one of the world’s first and still most famous pop videos, showing John at his white piano in Tittenhurst’s “big white room” while Yoko drifts round opening the shutters of its huge windows, ushering in the light of world peace.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

The rest of what cameraman Douglas Ibold describes as “thousands of hours” of footage has emerged in stages, beginning with 1988’s Imagine documentary, but there’s been nothing like the treasure trove revealed in Michael Epstein’s Above Us Only Sky. Here’s George Harrison helping out John with chords for “How”; a saucer-eyed Nicky Hopkins at the piano with John; Phil Spector, perpetually in shades, hovering like a malevolent imp; Lennon himself writhing as he spits out the words of “Gimme Some Truth” or crooning “Jealous Guy” to backings we can’t hear, just his voice, booth-strong and vulnerable.

It’s a mother lode for fans, enriched by the off-duty larks around Tittenhurst’s 99 acres, caught in the mellow glow of English midsummer: Lennon rowing Julian around the lake; reading aloud newspaper reports of the couple’s exploits over breakfast; the pair dressed up like Errol Flynn and Theda Bara, rich kids at play.

Although subtitled ‘The Making Of Imagine’, Epstein’s documentary extends back over the couple’s romance and forwards to New York City, where the pair moved in autumn ’71, as the album was released. Most of the supporting footage is well known – the bed-ins, the Toronto Peace festival, the Oz march, the Times Square billboards for “War Is Over” – with the emphasis on the couple’s role as cultural revolutionaries caught up in tumultuous times. Tariq Ali is on hand to remind us of the radicalising effect of the American war in Vietnam and Cambodia.

There are other agendas of course, notably Yoko’s promotion of herself as John’s creative equal. At this point the two were certainly in happy fusion. Lennon was by all accounts a changed man. Klaus Voormann, who played on the album and who had shared a foxhole or two with John back in Hamburg days, provides testimony to that, contrasting the Beatle he’d met on the “Strawberry Fields” shoot (“I’m so unhappy,” confided a tearful John) with the ebullient presence here.

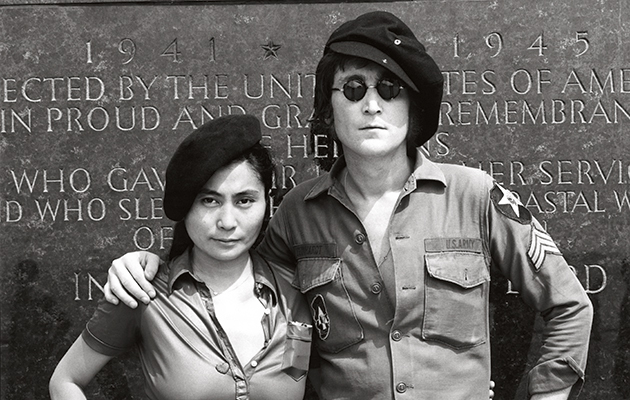

Others testify to the hostility directed at Yoko, a racist punishment beating from the media for the impertinence of falling in love with John and “stealing him from the British public”, as writer Ray Connolly puts it. With Yoko by his side, John could become what he had always wanted – an artist, entwined in creative and emotional communion with the ultimate art-school girl.

As John freely admitted – at least later on – “Imagine” itself was born under Yoko’s influence, the imperative to “imagine” taken from her book of poetic whimsies, Grapefruit (the scene in the limo en route to its launch is hilarious). Alas, Yoko’s musical talents, previously latent, could never match those of that other Lennon equal, Paul McCartney, never short of a concept or two himself.

Imagine did what Lennon intended, became a massive international success and spawned an anthem, making him a hitmaker again. The album’s star has fallen over the years, John admitting he’d “covered it in chocolate”, while several tracks now sound like B-sides, not least the self-demeaning “How Do You Sleep?”. On the other hand, “Gimme Some Truth” has rarely sounded so timely, the pastoral quietude of “Oh My Love” so enchanting.

The sacralised title track endures, despite its confection and contradictions, remaining what Ali describes as a “utopian manifesto”. Here’s a reminder that its creator was not just a dreamer but a charismatic, well-informed activist “selling peace like they sell their wars”. For the real behind-the-scenes dramas – the drugs, arguments, cruelty – you have to read the books.