Seven years after Johnny Cash’s death, and four years on from his first posthumous album, American V: A Hundred Highways, it’s hard not to approach this “new” record with suspicion. “These songs are Johnny’s final statement,” producer Rick Rubin said the last time round. What, then, does that make this collection? Can it be more than studio-floor sweepings, stitched together to keep the Cash industry ticking? The choice of opening title track does not allay those fears. Recorded in the early 1950s, Brother Claude Ely’s original “There Ain’t No Grave”, was a raw, raving slice of hillbilly gospel. The Cash who signed to Sun would have set the song on fire. Here, though, it’s all ashes. An ominous guitar picks out a lowering landscape, a desolate banjo circles, a drumbeat suggests mortal chains being dragged. And here is Cash’s voice, back from beyond, full of stern shadows, telling us this: “There ain’t no grave can hold my body down.” It’s almost as if the whole American Recordings project has been leading up to this marketing opportunity. The man we hear singing is exactly the man, the myth, presented back in 1994 on the cover of the first Cash/Rubin set – the black-clad preacher, returned in time for judgement day. Here, though, is the thing. Despite all this, because of all this, “Ain’t No Grave”, the song, sounds simply astonishing, a strange and hovering thing, truly, to set your hair on end. And after this bleak, goosebumpy opener, Ain’t No Grave, the album, turns decisively away from voguish gothic sonics to get plain and personal. These songs were recorded during the same sessions that produced A Hundred Highways, and, like that, mostly come drawn from older times. This was that final period when Cash was confined to a wheelchair by illness, when his sight was failing, and when he suffered the hardest blow of all, losing his wife, June. It feels like a man drawing in the things that matter to him. No Depeche Mode, no Nine Inch Nails. The closest to contemporary is Sheryl Crow’s “Redemption Day”, a song that promises “a train that’s heading straight to heaven’s gate,” which Cash, last king of the train song, instantly renders his own, sounding frailer, but closer than ever before. In the main, though, it’s Cash singing songs he could have (and in some cases did) cut during his first two decades recording. Not that familiarity makes it any easier to bear. Kris Kristofferson’s “For The Good Times,” for example, is a warm, simple, sad song to the end of a love affair – but hearing him singing the opening lines (“Don’t look so sad, I know it’s over”), Cash fans might find themselves weeping into their beer for a different reason. The run of songs that make up what would once have been the second side mount a particularly poignant flashback to the Cash of the ’60s. Ed McCurdy’s anti-war singsong “Last Night I Had The Strangest Dream” is one Cash performed at Madison Square Garden in 1969. Meanwhile, “Satisfied Mind”, sounds startlingly like it could have been culled from rehearsals in Folsom Prison in 1968. This is Rubin’s brilliance. God only knows how Cash found the strength to sing, but, while never denying the quavering fragility of his voice, these arrangements, sympathetic, spartan, largely acoustic, frame what remains so it’s only the strength – Cash’s abiding, defining characteristic – that you hear. It’s there again in the sole Cash composition “I Corinthians 15:55”. One of the last songs he wrote, it’s the most recent song here, but sounds the oldest. Based around the Bible passage that asks, “Oh death, where is thy sting..?” and built on front-parlour piano, it’s handmade, homespun, plain and proud as a needlework sampler, a nursery-rhyme of Christian belief, modest yet defiant. If, as stated, this really is to be the last Cash album (around 30 tracks from these final sessions apparently remain unreleased), it makes a fitting conclusion. The American Recordings project began with Rubin setting out to make Cash palatable to a new audience. Now it ends with Cash returning to what made him. Ten songs clocking in at 33 minutes, filled with cowboy tunes, trains, rivers, rambling, love, simple joys, righteous anger, deep regrets, death’s shadow, sentiment and, always, faith. Simultaneously an act of self-mythologising and of unfashionable sincerity. A Johnny Cash record, in other words. Damien Love

Seven years after Johnny Cash’s death, and four years on from his first posthumous album, American V: A Hundred Highways, it’s hard not to approach this “new” record with suspicion. “These songs are Johnny’s final statement,” producer Rick Rubin said the last time round. What, then, does that make this collection? Can it be more than studio-floor sweepings, stitched together to keep the Cash industry ticking?

The choice of opening title track does not allay those fears. Recorded in the early 1950s, Brother Claude Ely’s original “There Ain’t No Grave”, was a raw, raving slice of hillbilly gospel. The Cash who signed to Sun would have set the song on fire. Here, though, it’s all ashes. An ominous guitar picks out a lowering landscape, a desolate banjo circles, a drumbeat suggests mortal chains being dragged. And here is Cash’s voice, back from beyond, full of stern shadows, telling us this: “There ain’t no grave can hold my body down.”

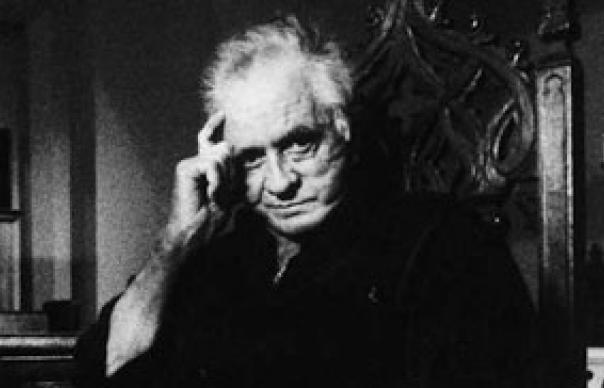

It’s almost as if the whole American Recordings project has been leading up to this marketing opportunity. The man we hear singing is exactly the man, the myth, presented back in 1994 on the cover of the first Cash/Rubin set – the black-clad preacher, returned in time for judgement day.

Here, though, is the thing. Despite all this, because of all this, “Ain’t No Grave”, the song, sounds simply astonishing, a strange and hovering thing, truly, to set your hair on end. And after this bleak, goosebumpy opener, Ain’t No Grave, the album, turns decisively away from voguish gothic sonics to get plain and personal.

These songs were recorded during the same sessions that produced A Hundred Highways, and, like that, mostly come drawn from older times. This was that final period when Cash was confined to a wheelchair by illness, when his sight was failing, and when he suffered the hardest blow of all, losing his wife, June. It feels like a man drawing in the things that matter to him. No Depeche Mode, no Nine Inch Nails. The closest to contemporary is Sheryl Crow’s “Redemption Day”, a song that promises “a train that’s heading straight to heaven’s gate,” which Cash, last king of the train song, instantly renders his own, sounding frailer, but closer than ever before.

In the main, though, it’s Cash singing songs he could have (and in some cases did) cut during his first two decades recording. Not that familiarity makes it any easier to bear. Kris Kristofferson’s “For The Good Times,” for example, is a warm, simple, sad song to the end of a love affair – but hearing him singing the opening lines (“Don’t look so sad, I know it’s over”), Cash fans might find themselves weeping into their beer for a different reason.

The run of songs that make up what would once have been the second side mount a particularly poignant flashback to the Cash of the ’60s. Ed McCurdy’s anti-war singsong “Last Night I Had The Strangest Dream” is one Cash performed at Madison Square Garden in 1969. Meanwhile, “Satisfied Mind”, sounds startlingly like it could have been culled from rehearsals in Folsom Prison in 1968.

This is Rubin’s brilliance. God only knows how Cash found the strength to sing, but, while never denying the quavering fragility of his voice, these arrangements, sympathetic, spartan, largely acoustic, frame what remains so it’s only the strength – Cash’s abiding, defining characteristic – that you hear.

It’s there again in the sole Cash composition “I Corinthians 15:55”. One of the last songs he wrote, it’s the most recent song here, but sounds the oldest. Based around the Bible passage that asks, “Oh death, where is thy sting..?” and built on front-parlour piano, it’s handmade, homespun, plain and proud as a needlework sampler, a nursery-rhyme of Christian belief, modest yet defiant.

If, as stated, this really is to be the last Cash album (around 30 tracks from these final sessions apparently remain unreleased), it makes a fitting conclusion. The American Recordings project began with Rubin setting out to make Cash palatable to a new audience. Now it ends with Cash returning to what made him. Ten songs clocking in at 33 minutes, filled with cowboy tunes, trains, rivers, rambling, love, simple joys, righteous anger, deep regrets, death’s shadow, sentiment and, always, faith. Simultaneously an act of self-mythologising and of unfashionable sincerity. A Johnny Cash record, in other words.

Damien Love