Motherlode: Spanning the decades with the Man in Black—59 albums-plus, across 63 discs... Johnny Cash was, and remains, the Mighty Oak of 20th-century popular music: singer, song-writer and collector, seeker, provocateur, folklorist, storyteller, historian, family man, outlaw, moralist, drug addict, TV and movie star, joker, preacher, philanthropist, spokesman for the downtrodden, musical bridge from the Carter Family to Nine Inch Nails . . . visionary. His high presence touched us all, even if some of us are only dimly aware of it. The Complete Columbia Album Collection, duly correcting decades-long, over-merchandising abuses of the Cash catalog, collects every official LP 1958-1985 as a monster 63-disc box. Along with countless hits and iconic songs, it turns up many dark corners and oddball efforts within a prolific, oft-bewildering discography: Christmas and children's discs, obscure soundtracks, import-only live albums, and historical/religious epics, plus three bonus discs of 1954-1958 Sun output and another 56 singles and guest spots. Bonus tracks and Bootleg Series material of more recent issue are conspicuously absent. Cash was, of course, an artist utterly without guile. If he sang it, you knew he connected with it, that he believed in it. His rugged, authoritative, whooping, growling, sometimes talk-singing vocals—featuring that Voice of God baritone—married to endless variations on the trademark Tennessee Three boom-chicka-boom, defined his spartan musicality. Country, blues, rockabilly, rock ‘n’ roll, gospel—it all just ended up sounding like Johnny Cash music. It was less about musical expansiveness than how much heart and soul (and faith, grace, righteousness, humor, social justice, and basic humanity) he could pack into the grooves, a stubborn, less-is-more motif that served him well. The true beauty in Cash's work came in flashing imagery of America (“Big River”), rich storytelling with a piquant edge, and as an eloquent, compassionate observer of human nature. And especially, when he spoke up for the poor, hopeless, imprisoned, which he did often: The sweeping sentiments of his signature song, "Man in Black," are emblematic of a large swath of his work: That is, that the human soul is worthy and deserving of redemption. He was hardly a conventional star, though; his career took a peculiar arc. His best-known work intersected with popular tastes and collective interests at key moments (especially, the country/Americana of his Sun beginnings, and the peerless prison albums); other times, his stubbornly chosen path resulted in works of little fanfare. He repeated himself, made remakes and could slide himself into the flimsiest of material. Everybody Loves a Nut, a vastly strange 1966 LP, shows just how off the rails Cash could go. With its Shel Silverstein novelties and egg-sucking dogs, it was anti-album, his Metal Machine Music. America, a drab (career-killing?) 1972 historical opus, was overboard the other way, static and bombastic. Beyond the weird stuff, the religio-documentarian sidesteps, and many fine if arch concept albums, lay works of unequivocal grandeur, particularly circa 1968-72. In covering talented, diverse writers (Kris Kristofferson, Tim Hardin, Billy Edd Wheeler, Jack Clement), and composing his own inspired, down-and-out anthems, came a barrage of sublime moments—“Sunday Morning Coming Down,” “To Beat the Devil,” “Darlin’ Companion,” “A Boy Named Sue,” “See Ruby Fall.” Cash stumbled circa 1973-79, succumbing to a kind of treacly sentimentalism; his once-vast audience moved on. The downturn, yielding many spotty albums but intermittently fabulous songs, is ripe for reevaluation: “Hit the Road And Go” (1977) is restless road song du jour; “My Old Kentucky Home” (1974) challenges Randy Newman’s original; the down-and-out Jean Ritchie nugget “The L&N Don’t Stop Here Anymore” (1979) is a natural. He turned a corner 1980-1983, producing a rousing trilogy: Rockabilly Blues (with son-in-law Nick Lowe and Rockpile), the Billy Sherrill-produced The Baron, and Johnny 99, which proved that, given proper material—two from Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska—he could be devastating as ever. No one much noticed, though. They would, finally, some 10 years later, courtesy of one Rick Rubin. Hills and valleys, warts and all, Complete Columbia is simply a singular, staggering body of work, throwing down challenges in all directions: Define yourself before someone else defines you; call your own shots, and call ’em as you seem ’em; don’t take shit from anybody, but never take yourself too seriously. And underline it all with a generous spirit of justice and love. Luke Torn

Motherlode: Spanning the decades with the Man in Black—59 albums-plus, across 63 discs…

Johnny Cash was, and remains, the Mighty Oak of 20th-century popular music: singer, song-writer and collector, seeker, provocateur, folklorist, storyteller, historian, family man, outlaw, moralist, drug addict, TV and movie star, joker, preacher, philanthropist, spokesman for the downtrodden, musical bridge from the Carter Family to Nine Inch Nails . . . visionary. His high presence touched us all, even if some of us are only dimly aware of it.

The Complete Columbia Album Collection, duly correcting decades-long, over-merchandising abuses of the Cash catalog, collects every official LP 1958-1985 as a monster 63-disc box. Along with countless hits and iconic songs, it turns up many dark corners and oddball efforts within a prolific, oft-bewildering discography: Christmas and children’s discs, obscure soundtracks, import-only live albums, and historical/religious epics, plus three bonus discs of 1954-1958 Sun output and another 56 singles and guest spots. Bonus tracks and Bootleg Series material of more recent issue are conspicuously absent.

Cash was, of course, an artist utterly without guile. If he sang it, you knew he connected with it, that he believed in it. His rugged, authoritative, whooping, growling, sometimes talk-singing vocals—featuring that Voice of God baritone—married to endless variations on the trademark Tennessee Three boom-chicka-boom, defined his spartan musicality. Country, blues, rockabilly, rock ‘n’ roll, gospel—it all just ended up sounding like Johnny Cash music. It was less about musical expansiveness than how much heart and soul (and faith, grace, righteousness, humor, social justice, and basic humanity) he could pack into the grooves, a stubborn, less-is-more motif that served him well.

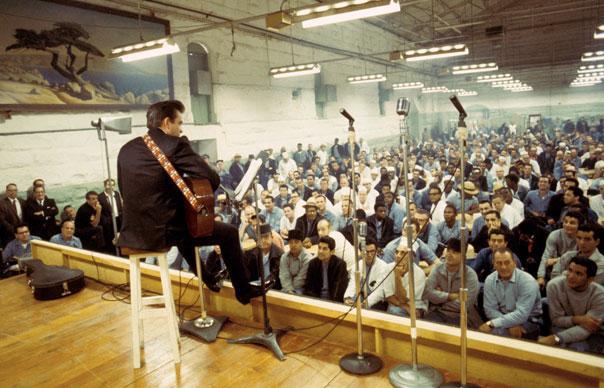

The true beauty in Cash’s work came in flashing imagery of America (“Big River”), rich storytelling with a piquant edge, and as an eloquent, compassionate observer of human nature. And especially, when he spoke up for the poor, hopeless, imprisoned, which he did often: The sweeping sentiments of his signature song, “Man in Black,” are emblematic of a large swath of his work: That is, that the human soul is worthy and deserving of redemption.

He was hardly a conventional star, though; his career took a peculiar arc. His best-known work intersected with popular tastes and collective interests at key moments (especially, the country/Americana of his Sun beginnings, and the peerless prison albums); other times, his stubbornly chosen path resulted in works of little fanfare. He repeated himself, made remakes and could slide himself into the flimsiest of material. Everybody Loves a Nut, a vastly strange 1966 LP, shows just how off the rails Cash could go. With its Shel Silverstein novelties and egg-sucking dogs, it was anti-album, his Metal Machine Music. America, a drab (career-killing?) 1972 historical opus, was overboard the other way, static and bombastic.

Beyond the weird stuff, the religio-documentarian sidesteps, and many fine if arch concept albums, lay works of unequivocal grandeur, particularly circa 1968-72. In covering talented, diverse writers (Kris Kristofferson, Tim Hardin, Billy Edd Wheeler, Jack Clement), and composing his own inspired, down-and-out anthems, came a barrage of sublime moments—“Sunday Morning Coming Down,” “To Beat the Devil,” “Darlin’ Companion,” “A Boy Named Sue,” “See Ruby Fall.”

Cash stumbled circa 1973-79, succumbing to a kind of treacly sentimentalism; his once-vast audience moved on. The downturn, yielding many spotty albums but intermittently fabulous songs, is ripe for reevaluation: “Hit the Road And Go” (1977) is restless road song du jour; “My Old Kentucky Home” (1974) challenges Randy Newman’s original; the down-and-out Jean Ritchie nugget “The L&N Don’t Stop Here Anymore” (1979) is a natural.

He turned a corner 1980-1983, producing a rousing trilogy: Rockabilly Blues (with son-in-law Nick Lowe and Rockpile), the Billy Sherrill-produced The Baron, and Johnny 99, which proved that, given proper material—two from Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska—he could be devastating as ever. No one much noticed, though. They would, finally, some 10 years later, courtesy of one Rick Rubin.

Hills and valleys, warts and all, Complete Columbia is simply a singular, staggering body of work, throwing down challenges in all directions: Define yourself before someone else defines you; call your own shots, and call ’em as you seem ’em; don’t take shit from anybody, but never take yourself too seriously. And underline it all with a generous spirit of justice and love.

Luke Torn