Finding some groundless, fleeting joy at the end of a very soggy rainbow, Mike Waterson concludes Bright Phoebus – the giddy 1972 ensemble piece he fronted with his younger sister, Lal – with a little rapture. “No more clouds, no more rain,” he burbles wistfully, accent broad and vowels flat...

Finding some groundless, fleeting joy at the end of a very soggy rainbow, Mike Waterson concludes Bright Phoebus – the giddy 1972 ensemble piece he fronted with his younger sister, Lal – with a little rapture. “No more clouds, no more rain,” he burbles wistfully, accent broad and vowels flat as the Humber Estuary. The sun is shining. Despite all evidence to the contrary, there is hope.

The long, troubled saga of Mike and Lal’s slow-burning tour de force perhaps vindicates that naïve belief. Neither Lal (who died in 1998) nor Mike (2011) have lived to see Bright Phoebus receive the honour of a dignified official reissue, but this crystal-clear, remastered version – complemented by the siblings’ weird and wobbly home demos – does belated justice to a record regarded by many on release as a disgrace to the Waterson name.

Orphaned young – their father killed by a series of strokes not long after their mother died following an asthma attack – the three Waterson siblings (Norma, Mike and Lal) were raised in Hull on a diet of hymns, party pieces and folk songs by their grandmother, Eliza Ward. Inspired by the folk revival, they took their sandblaster-strength strain of harmonising south, their repertoire of traditional songs from their native Yorkshire proving to be quite the hit in rooms above pubs. However, life as professional singers soon became a drag, and in 1968 they called it a day, Norma heading abroad with her fiancé to Montserrat.

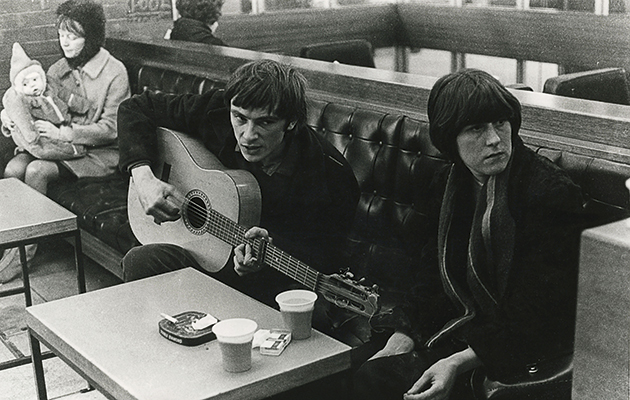

Back on Humberside and somewhat bereft, the younger Watersons felt something musical stirring, young mother Lal’s regular lunchtime visits from painter and decorator Mike taking on a new intensity when they realised they were both writing songs – something neither would have countenanced in their days on the folk circuit. Mike’s were an idiosyncratic mix of rockabilly and music hall; Lal’s a vinegary, jagged-edged acoustic gothic. When future Mr Norma Waterson, Martin Carthy, first heard them, he was blown away. When his Steeleye Span bandmate Ashley Hutchings got to listen, he swiftly gathered together a basic ensemble to help fashion them into a record, roping in Carthy as well as fellow Fairport Convention alumni Richard Thompson and Dave Mattacks. Recorded over a week in a basement room at Cecil Sharp House, home of the trad-dads of the English Folk Dance And Song Society, it represented an abrupt shift away from anything the Watersons had done.

Mike’s punning opener, “Rubber Band” (“Just like margarine our fame is spreading,” he chortles), gives scant indication of the raw strangeness of what follows. First, Lal’s “The Scarecrow”, sung tremulously by Mike over a mildly Astrud Gilberto strum. Its plea for acceptance in a cold world is abruptly overtaken by a pagan death rite: “And to a stake they tied a child new born,” he sings, mildly overawed. “And the songs were sung/The bells were rung, and they sowed the corn.” It is not the only innocent life to be lost on Bright Phoebus, Lal apparently still working through her grief following the stillbirth of her son’s twin sister. The extraordinary “Child Among The Weeds” is her cubist response to that personal tragedy. Recorded in one cathartic take, the seagull-voiced Lal obliquely documents her warring feelings of love and grief, the song taking a violent metaphysical turn when Geordie folkie Bob Davenport takes over the narrative. His siren call “fly bird fly on your raven wing” feels like the stirring of something primal and huge. The relief is overpowering: “Sing for the love of weeping and burning,” Lal bellows. “And sing for the love of wheeling and turning,” Davenport responds.

“To Make You Stay”, a nebulous love song accompanied deftly by Thompson and Carthy on acoustic guitar, feels like an echo of that same emotional thunderclap. The “pretty little starling” that “flew away in the night time from under my right arm” was a profound loss indeed. Fate is no less cruel to Lal’s own Eleanor Rigby, “Winnifer Odd”. Seemingly accompanied by Django Reinhardt after a tough day at the fish market, Lal recounts a life of dead ends, destiny conspiring to deprive her stoic heroine of an education and a partner, before allowing her to be squished by a passing car while leaning over to “pick up a glittering thing”. A Rimbaud obsessive, she must have allowed herself a quiet twinkle of satisfaction at her pay-off line: “And she waited for death to come and wrap her up warm, but he never came.”

The Reaper misses another appointment on “Never The Same”, Lal’s rain-sodden take on nuclear apocalypse capturing her luckless survivors wearily lamenting; Norma, newly returned from abroad, steps in to sing, more resignation than anger in the words, “Sunny, sunny days, changed over to filthy weather.”

Coldness, though, may have been something Lal yearned for; her unusual romantic hero on “Fine Horseman” – as covered by Anne Briggs on 1971’s The Time Has Come – has a hard, chill cast, and her startling self-portrait, drunk and “flat on my back in the rainbow rain” on “Red Wine Promises” is defiant in its abjection. “Don’t need no bugger’s arms around me,” she snarls.

Lal’s songs are Bright Phoebus’ most compelling features, and – in addition to a larval “The Scarecrow” with her vocals – the demo disc includes another less-documented one, “Song For Thirza”. Her emotional apology to the lady her grandmother took from the workhouse to raise the children, she possibly considered it a little too direct for public consumption at this stage, Norma taking it out of mothballs to record it decades later. By contrast, Mike’s “One Of Those Days” and the moody “Jack Frost” may have been regarded as a little too intense. He provides necessary light relief on the finished record with Play School interlude “The Magical Man”, rockabilly death trip “Danny Rose”, and – most crucially – the leavening optimism of the title track. “Today Bright Phoebus she smiled down on me for the very first time,” he repeats, guileless, grateful, as his sisters, Carthy and visiting Steeleye Spanners Tim Hart and Maddy Prior chorus in behind him.

Reviews were positive, but much of the Watersons’ core trad-orthodox audience hated Bright Phoebus, and its songs were set aside once the three siblings returned to the stage. Lal eventually retired owing to ill health, the former art student spending her final years painting and sneaking out two albums recorded with her son, Oliver Knight, before succumbing to cancer at 55.

Her brother lived long enough to receive belated acclaim for Bright Phoebus, but while there was a tribute album in 2002 and a series of commemorative concerts from 2013, the original album remained largely off catalogue. Until now. Watersons unknown having kept the original master tape stashed away for decades, this new version has a heft that the original vinyl pressings lacked, wavering notes that seemed like spiderish scribbles transformed into determined scratches. Powerful, strange, and brighter than ever.