When Laurie Styvers died in 1998, aged 48, obituaries apparently entirely failed to recall her bohemian musical incarnation almost three decades earlier. No wonder, really. Recent years had been spent running an animal sanctuary in Texas, where she’d been born Laurette Stivers; her two albums, 1971’s Spilt Milk and 1973’s The Colorado Kid, were already long forgotten. Her one brush with success, her debut’s breezy, evergreen opener, “Beat The Reaper”, had also missed the charts even after British radio play, and despite Alan Freeman’s support, a follow-up 7”, The Colorado Kid’s playful, banjo-embellished “All American Long Haired Denimed Song-Writing Guitar Man”, joined her catalogue in obscurity.

When Laurie Styvers died in 1998, aged 48, obituaries apparently entirely failed to recall her bohemian musical incarnation almost three decades earlier. No wonder, really. Recent years had been spent running an animal sanctuary in Texas, where she’d been born Laurette Stivers; her two albums, 1971’s Spilt Milk and 1973’s The Colorado Kid, were already long forgotten. Her one brush with success, her debut’s breezy, evergreen opener, “Beat The Reaper”, had also missed the charts even after British radio play, and despite Alan Freeman’s support, a follow-up 7”, The Colorado Kid’s playful, banjo-embellished “All American Long Haired Denimed Song-Writing Guitar Man”, joined her catalogue in obscurity.

That’s how things might have remained had music historian Alec Palao and New York’s High Moon Records not released Gemini Girl: The Complete Hush Recordings in 2023. Before their intervention, most investigating her work would have found little more than critic Robert Christgau’s mean-spirited review of Spilt Milk in Rock Albums Of The 70s. Deeming her an “LA airhead” – though she’d spent her late teens in London, not Laurel Canyon – he crucified her as “so trite and pretty-poo in her fashionably troubled adolescence that you hope she chokes on her own money”. That’s despite the record being licensed by Mo Austin just before he became Warner Brothers’ chairman, and her contributions to psych-folk act Justine’s sole eponymous 1970 album, which currently commands silly money.

Perhaps Christgau was offended by Styvers’ status as an oil engineer’s daughter whose family had relocated to England, where she was educated at the capital’s private American School. Certainly, he’d have relished how The Colorado Kid lacked a US release. Nonetheless, that 2CD set has ensured that those raised on, say, either Laura Nyro and Dory Previn or Weyes Blood and Angel Olsen would do well to add Styvers to their collection. Let Me Comfort You now extends that invitation to vinyl by compiling the set’s previously unreleased material.

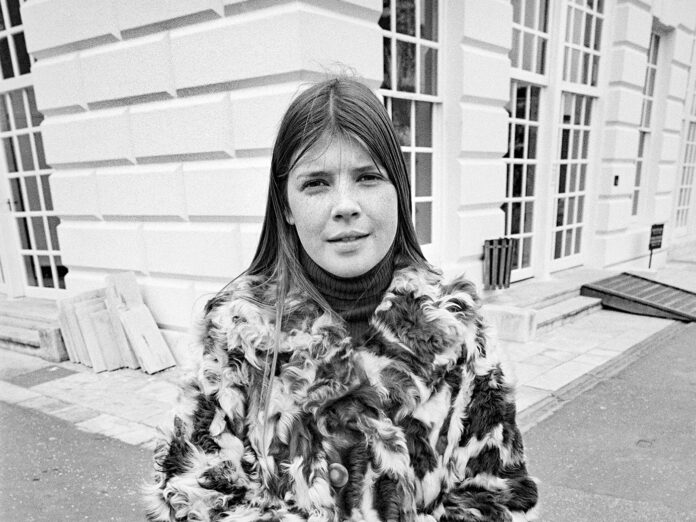

Admittedly, her most consistent charms lie in her studio albums, produced by Shel Talmy protégé Hugh Murphy, who’d together set up Styvers’ home, Hush Recordings. Spilt Milk’s “All I Ever Had”, with double-tracked vocals, could be The Carpenters, and “Pigeons” – all hammered pianos and oompah brass – a “When I’m 64”-fixated Harry Nilsson; The Colorado Kid’s title captures her fondness for the state where her parents kept a cabin as much as its wide-eyed “Oh Colorado” distills her frequent pastoral leanings and kinship with Carole King. Her heart-on-sleeve gifts, meanwhile, are best encapsulated in the understated, unaffected innuendo of the latter’s “You Be The Tide, I’ll Be The Bay”, its candid desire for a “salty old man” – still 22, she and Murphy, five years older, were now lovers – matched by the cover shot’s babyfaced Drew Barrymore innocence.

Still, Let Me Comfor You’s 11 tracks showcase such qualities impressively, her straightforward sweetness evident in a scaled-back, piano-and-strings version of the extravagant Spilt Milk track that gave 2023’s compilation its name. It’s there, too, in “God Knows The Reason”’s sparse yearning and an “All I Ever Had” demo, one of the rare times she, not arranger Tom Parker – fresh from Mac and Katie Kissoon’s lesser known “Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep” – plays piano.

She’s at ease amid bigger arrangements, too, with the wise-beyond-her-years “The Way I Should Stay” lifted by brass. The title track, too, balances disheartened loneliness with affectionate embraces, its Karen Carpenter purity – “I wish I was someone else’s fool” – mirrored, despite an oddly cutesy vocal, in an early recording of The Colorado Kid’s “White Flowers”.

1972’s glossier “If You Don’t Write Me Soon”, brightened by chiming glockenspiels and a swaggering instrumental break, is similarly imbued with wide-eyed nostalgia, and “Crazy Rainy Spring”, fuelled by Henry Spinetti’s drums, even flirts with funk, though that’s nothing next to “Crazy Rainy Spring”’s split-stereo, fuzz-guitar flourishes.

Suitably, Let Me Comfort You concludes with the warm-hearted, gratifying “Now That The Rain Has Stopped”, its pragmatic romance – “We both came out OK, I think” – indicative of Styver’s levelheaded yet affecting craft. Naturally, she’s worthy of higher praise than either her own or Christgau’s, but, a quarter century after her demise, she now has another chance to beat the reaper at last.