The first three albums plus extra material from the Page archives... A musician’s catalogue is his castle; its strength not defined by how much it changes, but how far it stays the same. In the case of Led Zeppelin, that castle has a vigilant gatekeeper. Of the group’s surviving members, one now makes platinum-plated Americana for an imagined hippy society. Another stalks a black ambient Mordor in the company of adventurous Norwegians. And then there’s Jimmy Page. Page is a musician who now has a curious relationship with his own band. In the 1960s and 1970s he controlled Led Zeppelin down to the smallest detail: selecting the players, paying for the sessions, retaining control of the masters. The devil, so to speak, was in the detail. Only having confirmed the security of his initial position, could he go on to contrive his most extravagant flourishes. Since the band’s 1980 demise, however, Page’s – relative – reluctance to make new music has meant he has become the de facto architect of the Zeppelin legacy, painstakingly curating his historic work. The 2007 Led Zeppelin 02 show seemed to suggest that there might soon be new chapters to the Zeppelin story – but the lack of movement in seven years suggests that Page, who once held all the cards, has seen a recalibration of his power. Is he still Led Zeppelin’s master? Or has he now become its servant? These new editions of the first three Led Zeppelin albums, which begin a campaign of attractive vinyl/CD reissues of the catalogue, do all they can to assert the former. To Page’s ears, the advent of “streaming and MP3s” warranted giving the catalogue additional polish. These new reissues duly derive from work done on them prior to their soft release on iTunes in 2012. Led Zeppelin audio is a heavy scene, as anyone who has spent time on messageboard threads called ‘“Gallows Pole”: Left or Right channel?’ will know. Many rate the original “Diament” CD transfers, mastered by Barry Diament in 1987 over the initial “Page/Marino” ’92 remasters. John Davis, who brought a crisp loudness to 2007’s Mothership and Celebration Day, isn’t entirely popular in this world – but his well-articulated and fruity sound here isn’t going to disappoint the sensible listener. Certainly not John Paul-Jones, whose warm, busy bass playing and deep Rhodes piano are both big winners here. All done from transfers of the original – apparently unplayed – master tapes, these feel a little less “loud” than Mothership. Still, whether you’re listening flicking through the 70 page deluxe book while listening to your audiophile vinyl, or on the tube vibing to your device, familiar features feel vibrant. That odd off-mic shout during “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You”. The whump that shakes the room immediately before the guitar solo in “Whole Lotta Love”. Or “Since I’ve Been Loving You”, the song that details the empathetic Page/Plant musical relationship in a tender seven and a half minutes. Whatever defines your relationship with the first three Led Zeppelin albums, you will find it here, as involving as ever. What did we expect, though? Bad sound? Aswell as the detailed replica packaging (though not so detailed we get plum and red labels), the selling point of these reissues is a previously unexplored aspect of the Zeppelin catalogue: extra material, judiciously selected by Page from his (two) archives. What you’ll be appreciating here, however, isn’t exactly a treasure house of undiscovered gems. III’s “Keys To The Highway” is a pleasant reminder, were one needed, that Page and Plant were connoisseurs of the blues. “La La” is an wordless Hammond number but becomes a compendium of LZII guitar tropes, more production showcase than song. “Jennings Farm Blues” and “Bathroom Sound” are works-in-progress for other LZIII tracks (“Bron –Yr-Aur Stomp”; “Out On The Tiles”). Instead, the additional material on II and III is not misleadingly referred to as “companion audio”, and directs our attention to the tacit purpose of these reissues: to remind us of the editorial talents of Jimmy Page, Producer. “Whole Lotta Love” is a decent place to begin. As we hear it on the second disc, much of the track is in place, but there is simply reverberating space in the cavern later populated by Theramin, and a heavy-breathing Robert Plant. It’s maybe not the revelation Page imagines, but it does endorse the value in what he recently described in as the “filigree work” that completes a Led Zeppelin song. They didn’t just throw this stuff together, you know. III, often overlooked, will surely win new converts. Supposedly some kind of low-fi Wiccan hoedown, the detail of the remaster reveals the space and structure in the songs (particularly the backing vocals), and the degree to which the band derived its sound not only from country, blues and folk, but also – like Deep Purple – from progressive pop. “Out On The Tiles” claims its seat at the table of big hitters, while the comparison disc is particularly interesting for “Immigrant Song”. You know something sounds odd. It’s because the one that sounds finished is the demo. The one with the hissy metronome and count-in is the finished one. On headphones, odd studio acoustics reveal themselves. Page’s notion of what might catch the ear was eccentric, but generally infallible. Duly, these remasters aren’t asking you to extend your idea of the Zeppelin canon, but retract it – to realize why the albums have the power and mystery they do. The reason there aren’t more songs is because control – over quality, over everything – was, and is, very high. The disc released to accompany I has been subjected to just this rigour. The live show, from Paris in November 1969 (note to audiophiles: a mono recording, sent over to Page in an email) has had its “How Many More Times” edited down by 50 per cent (to 11 minutes), while “Moby Dick” (omitted from the original French radio broadcast) has been reinstated. An entertaining exchange between Page and Plant in which the pair refer to “White Summer” as “the wanking dog” has been excised. You might wonder at the inclusion of this, more II than I show here (rather than, say, some “New Yardbirds”-era stuff), and then the band begin to play. It’s “Good Times, Bad Times”. But that’s proves to be a deliberate false beginning – it’s now “Communication Breakdown”, and it seems like the song’s going far too fast. It sounds as if Jimmy Page is never going to be able to pull off a solo at that velocity, that the wheels are going to come off completely. But then you listen again and get the picture. No need for alarm. Then as now, Jimmy Page knows precisely what he’s doing. John Robinson

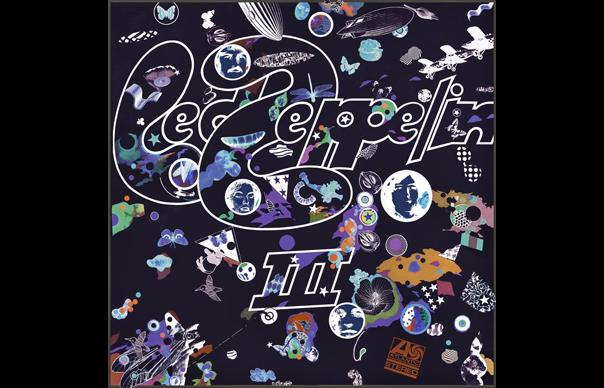

The first three albums plus extra material from the Page archives…

A musician’s catalogue is his castle; its strength not defined by how much it changes, but how far it stays the same. In the case of Led Zeppelin, that castle has a vigilant gatekeeper. Of the group’s surviving members, one now makes platinum-plated Americana for an imagined hippy society. Another stalks a black ambient Mordor in the company of adventurous Norwegians. And then there’s Jimmy Page.

Page is a musician who now has a curious relationship with his own band. In the 1960s and 1970s he controlled Led Zeppelin down to the smallest detail: selecting the players, paying for the sessions, retaining control of the masters. The devil, so to speak, was in the detail. Only having confirmed the security of his initial position, could he go on to contrive his most extravagant flourishes.

Since the band’s 1980 demise, however, Page’s – relative – reluctance to make new music has meant he has become the de facto architect of the Zeppelin legacy, painstakingly curating his historic work. The 2007 Led Zeppelin 02 show seemed to suggest that there might soon be new chapters to the Zeppelin story – but the lack of movement in seven years suggests that Page, who once held all the cards, has seen a recalibration of his power. Is he still Led Zeppelin’s master? Or has he now become its servant?

These new editions of the first three Led Zeppelin albums, which begin a campaign of attractive vinyl/CD reissues of the catalogue, do all they can to assert the former. To Page’s ears, the advent of “streaming and MP3s” warranted giving the catalogue additional polish. These new reissues duly derive from work done on them prior to their soft release on iTunes in 2012.

Led Zeppelin audio is a heavy scene, as anyone who has spent time on messageboard threads called ‘“Gallows Pole”: Left or Right channel?’ will know. Many rate the original “Diament” CD transfers, mastered by Barry Diament in 1987 over the initial “Page/Marino” ’92 remasters. John Davis, who brought a crisp loudness to 2007’s Mothership and Celebration Day, isn’t entirely popular in this world – but his well-articulated and fruity sound here isn’t going to disappoint the sensible listener. Certainly not John Paul-Jones, whose warm, busy bass playing and deep Rhodes piano are both big winners here.

All done from transfers of the original – apparently unplayed – master tapes, these feel a little less “loud” than Mothership. Still, whether you’re listening flicking through the 70 page deluxe book while listening to your audiophile vinyl, or on the tube vibing to your device, familiar features feel vibrant. That odd off-mic shout during “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You”. The whump that shakes the room immediately before the guitar solo in “Whole Lotta Love”. Or “Since I’ve Been Loving You”, the song that details the empathetic Page/Plant musical relationship in a tender seven and a half minutes. Whatever defines your relationship with the first three Led Zeppelin albums, you will find it here, as involving as ever.

What did we expect, though? Bad sound? Aswell as the detailed replica packaging (though not so detailed we get plum and red labels), the selling point of these reissues is a previously unexplored aspect of the Zeppelin catalogue: extra material, judiciously selected by Page from his (two) archives. What you’ll be appreciating here, however, isn’t exactly a treasure house of undiscovered gems. III’s “Keys To The Highway” is a pleasant reminder, were one needed, that Page and Plant were connoisseurs of the blues. “La La” is an wordless Hammond number but becomes a compendium of LZII guitar tropes, more production showcase than song. “Jennings Farm Blues” and “Bathroom Sound” are works-in-progress for other LZIII tracks (“Bron –Yr-Aur Stomp”; “Out On The Tiles”).

Instead, the additional material on II and III is not misleadingly referred to as “companion audio”, and directs our attention to the tacit purpose of these reissues: to remind us of the editorial talents of Jimmy Page, Producer. “Whole Lotta Love” is a decent place to begin. As we hear it on the second disc, much of the track is in place, but there is simply reverberating space in the cavern later populated by Theramin, and a heavy-breathing Robert Plant. It’s maybe not the revelation Page imagines, but it does endorse the value in what he recently described in as the “filigree work” that completes a Led Zeppelin song.

They didn’t just throw this stuff together, you know. III, often overlooked, will surely win new converts. Supposedly some kind of low-fi Wiccan hoedown, the detail of the remaster reveals the space and structure in the songs (particularly the backing vocals), and the degree to which the band derived its sound not only from country, blues and folk, but also – like Deep Purple – from progressive pop. “Out On The Tiles” claims its seat at the table of big hitters, while the comparison disc is particularly interesting for “Immigrant Song”. You know something sounds odd. It’s because the one that sounds finished is the demo. The one with the hissy metronome and count-in is the finished one. On headphones, odd studio acoustics reveal themselves.

Page’s notion of what might catch the ear was eccentric, but generally infallible. Duly, these remasters aren’t asking you to extend your idea of the Zeppelin canon, but retract it – to realize why the albums have the power and mystery they do. The reason there aren’t more songs is because control – over quality, over everything – was, and is, very high.

The disc released to accompany I has been subjected to just this rigour. The live show, from Paris in November 1969 (note to audiophiles: a mono recording, sent over to Page in an email) has had its “How Many More Times” edited down by 50 per cent (to 11 minutes), while “Moby Dick” (omitted from the original French radio broadcast) has been reinstated. An entertaining exchange between Page and Plant in which the pair refer to “White Summer” as “the wanking dog” has been excised.

You might wonder at the inclusion of this, more II than I show here (rather than, say, some “New Yardbirds”-era stuff), and then the band begin to play. It’s “Good Times, Bad Times”. But that’s proves to be a deliberate false beginning – it’s now “Communication Breakdown”, and it seems like the song’s going far too fast. It sounds as if Jimmy Page is never going to be able to pull off a solo at that velocity, that the wheels are going to come off completely. But then you listen again and get the picture. No need for alarm. Then as now, Jimmy Page knows precisely what he’s doing.

John Robinson