The last few years, it would appear, have been full of change for the elusive singer-songwriter Liam Hayes. Long identified with Chicago’s scene – his classic debut single from 1994, “Found A Little Baby”, and first album, More You Becomes You, both released under the name Plush, reached the...

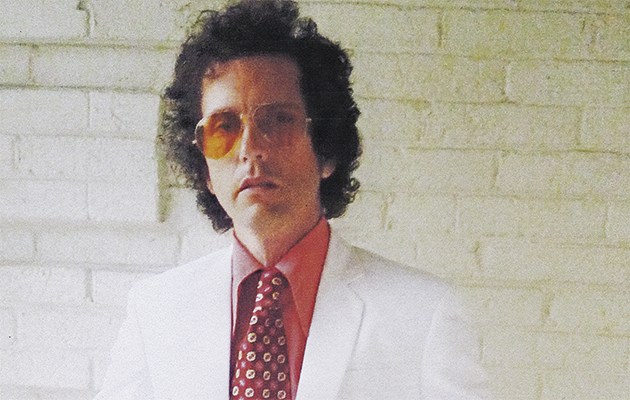

The last few years, it would appear, have been full of change for the elusive singer-songwriter Liam Hayes. Long identified with Chicago’s scene – his classic debut single from 1994, “Found A Little Baby”, and first album, More You Becomes You, both released under the name Plush, reached the outside world via the city’s Drag City imprint – Hayes shook things up by moving to Milwaukee. Not a huge move by any means, as the road trip is barely 100 miles, but for Hayes it was significant: “I’d lived my whole life in Chicago,” he says, “so I guess in many ways it had come to define me, or had at least provided other people with a basis for defining me.”

Hayes approaches most things with care and curiosity, and he also doesn’t do things by halves. “A few years later,” he continues, “just to make sure that I wasn’t missing out on anything, I did a stint on the west coast. I kissed the ground as soon as I got back here.” But there seemed to be other things brewing: in the notes accompanying Mirage Garage, only his sixth album in 24 years, he mentions that his prior album, 2015’s Slurrup, “was supposed to be a new beginning, but it turned out to be an ending both personally and professionally.”

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

It’s tempting to think of Hayes as unlucky – consider the story around 2002’s extravagant opus, Fed, which cost a six-figure sum to make and would eventually find initial release only in Japan, as no one-elsewhere would cough up Hayes’s asking price. Certainly, he’s an artist of high standards, and his vision of music, one where baroque ’60s pop meets lushly orchestrated soul, melancholy singer-songwriter tearjerkers a la Laura Nyro and Todd Rundgren, and Kinksian rockers, asks a lot of both Hayes’s songwriting, and his collaborators. But for all the mythology around Hayes as a “man out of time”, his music seems to be finding its own way; he’s stayed true to his vision and let the world assemble itself around him.

And if his time on the West Coast was troubled, it did, at least, give him the chance to record with producer Luther Russell, in the latter’s home studio in Pasadena. There was no grand plan: Hayes was simply getting his songs down, “without any expectations,” he clarifies. “We weren’t recording it with any idea of releasing it and I think that allowed me to be completely candid.” And indeed, Mirage Garage feels the most disarmed that Hayes has yet been. Its sound is relatively denuded, at least compared to the rococo flourishes of albums like Fed and Bright Penny: here there’s a real sense of two excitable friends in the back room, making music for sheer pleasure.

So, the second half of Mirage Garage, such as the Beatlesque stomp of “Eat In Sin”, shows that Hayes and Russell can simply let it roll, making music that’s full of light and play. The first side’s closer, “Herr Garage”, is Hayes at his most wicked, a drunken kazoo scrawling over a shuffle that’s like acoustic T. Rex at its silliest – which, of course, was also acoustic T. Rex at its most profound. All this comes, though, after Hayes has delivered a devastating one-two punch at the album’s start: the ghostly, drifting “In Me/Again”, performed through a shroud haze of nostalgia, where Hayes reflects, sometimes ruefully, on his history. It’s one of his most affecting, heart-wrenching songs, all the more powerful for its simple setting – sweeping acoustic guitars, gently brushed drums and Hayes’s pirouetting falsetto.

Following “In Me/Again” is “Here In Hell”, where Hayes turns his focus to the technological age. “I don’t need a screen or batteries or wires,” he ruminates, “’cos I’ve still got my brain.” From there, Hayes explores his feelings, watching those around him disappear into an info-tech nightmare. “Most everyone I knew had become bewitched by all this arid technology,” he recalls. “I rejected the programme and realised that in doing so, I had become part of an oppressed minority.” Strangely, Hayes has come out with something close to a Marxist hymn on labour relations, writing on the way our every act becomes a “cybernetic commodity” articulated through the online mediascape: “You are an unpaid electronic assembly line worker,” he argues. “Snout to tail, everyone and everything gets used.”

It’s a surprise to hear Hayes talking, and singing, so clearly about the socio-political malaise we find ourselves in these days. This is just one of the many surprises of Mirage Garage. Elsewhere, the acoustic reminiscence of “The More I Live” has the same gentle finesse of Colin Blunstone’s 1971 orch-pop classic, One Year; the crystalline guitar and clattering percussion of “Masters & Slaves” could be an early Gibb Brothers demo gone slightly bossa nova; “Amazing Astronauts”, punctuated by Russell’s pointillist percussion, is a slow reveal, sung from the bottom of a well.

Indeed, the sparseness and intimacy of the album feels like a new development for Hayes – unlike his previous, minimalist gem, 1998’s piano-and-vocals More You Becomes You, this feels less like a set piece, a through-composed performance, and more a great songwriter shading in an excellent set of songs with the gentlest of brushstrokes. Somehow, through some adverse conditions, Hayes has managed to pull off another idiosyncratic pop album, one that communicates more intimately and directly than ever before. Welcome back, Liam.