In 1993 Liz Phair seemed to come out of nowhere to upend indie rock. She had a deal with Matador Records, which was then home to Pavement and Superchunk, and she had a debut, Exile In Guyville, which was a hit before it was even released. The album was audacious in every way: musically, lyrically, e...

In 1993 Liz Phair seemed to come out of nowhere to upend indie rock. She had a deal with Matador Records, which was then home to Pavement and Superchunk, and she had a debut, Exile In Guyville, which was a hit before it was even released. The album was audacious in every way: musically, lyrically, emotionally, sexually, even visually. She appeared nearly topless on the cover, her left nipple half-cropped out of the frame, but she revealed even more of herself in songs like “Fuck And Run” and “Divorce Song”, her unrestrained confessionalism recalling Fleetwood Mac and her careerism at odds with a generation still highly sceptical of success. Billed as a song-for-song response to The Rolling Stones’ 1972 double epic Exile On Main Street, Guyville bristled and bared its teeth, daring you to dismiss it or its creator.

Such a meteoric rise from nobody to Gen X mouthpiece churned up a backlash that made her “the most hated woman in Chicago”, as her friend and drummer Brad Wood told the Chicago Tribune in 1994. But Phair was no overnight success. She’d been defining and refining her music for years, although she took a circuitous route to notoriety that bypassed all the ways her peers had paid their dues. What’s remarkable about this new boxset is its emphasis on the build-up to her debut rather than its aftermath, portraying her as a very deliberate artist striving to raise her voice in a scene that often drowned out women.

Initially, Phair’s ambitions were hardly musical. In college she studied visual art and interned with feminist artist Nancy Spero and painter Ed Paschke, and those experiences would eventually inform her recordings as much as any musical influence would. Returning home to suburban Chicago after an inauspicious year in San Francisco, Phair taught herself to play guitar, devising her own tunings and techniques she describes as painterly. Holed up in her bedroom at her parents’ house, Phair wrote songs the way others might keep a diary, setting her most intimate thoughts to rough guitar chords. That privacy allowed her a greater sense of candour than she would have mustered if she’d been fronting a band or performing at open-mic nights.

She recorded some of these early compositions on a four-track and made cassettes for a few friends. She christened the tapes Girly Sound, which wasn’t so much a band name or musical identity – more like a sardonic jab at genre labels in what she recognised as a male-dominated field. That initial collection was never intended for commercial release, but the feedback was so encouraging that she made two more Girly Sound collections to circulate well beyond her circle of friends.

Many of the songs on Guyville and later studio albums started out in primitive – but not tentative – form on these cassettes, which made them something like a holy grail for Phair’s fans. Until now, however, they’ve been more legend than reality. A few of the recordings ended up on the “Juvenilia” EP in 1995, and a few more were appended to the 15th-anniversary edition of Guyville in 2008. Another handful were included on a bonus disc with her otherwise forgotten 2010 album Funstyle. Mostly the tapes were distributed as bootlegs, although the format changed with the technology: first as cassette, then on burned CDs, then as MP3s.

The Girly tapes have the documentary quality of old field recordings – unpolished, unproduced, unpretentious. It’s just Phair alone with her thoughts and her guitar, and on most of the tracks, particularly those recorded in her bedroom but even a few later studio cuts, the hum of the room is audible, as though she’s captured her own solitude on magnetic tape. Her songwriting is irreverent and sometimes caustic, hilarious and occasionally sombre, horny and angry and dramatic and even melodramatic. “Free love,” Phair sings on “Hello Sailor”, “is a whole lot of bullshit”. Neither love nor art is free in these songs or in the world they depict. Everything is transactional. Someone always pays.

“It’s nice to be liked, but it’s better by far to get paid,” she sings on “Money”. “I know that most of the friends that I have don’t really see it that way.” She retitled the song “Shitloads Of Money” when she recorded it for 1998’s Whitechocolatespaceegg, but it sounds steelier, far more transgressive in this lo-fi version. There’s a sharp crackle in her voice, a withering brush-off to the keep-it-real crowd. Less effective is “Wild-Thing”, a sour diss of a materialistic woman that’s most notable for the way Phair rewrites the Troggs’ radio staple of the same title. That’s one of so many rock and soul references embedded in her songs. “Slave” commandeers the chorus of The Jesus & Mary Chain’s “Head On” and melds it to an old jump-rope rhyme. “Easy Target” includes snippets of both Betty Everett’s 1964 hit “Shoop Shoop (It’s In His Kiss)” and The Contours’ 1962 smash “Do You Love Me?”. Phair slyly alters them as a plea to a lover to shut up: “So the next time we make love, drop the words, just do the stuff/Speak softly and use that big stick.”

Almost from the beginning she is interrogating rock history, using it the ways hip-hop MCs sampled old breakbeats. She would expand that approach on Exile In Guyville, appropriating not just a song but a full double album by the Stones – who were equally schooled in appropriating older tunes. Her official debut might have its conceptual roots in the work of Spero and Paschke and other contemporary artists, as it shows Phair thinking about what the album can be as an art object – not just how it sounds, but what it does. Guyville is a kind of sculpture or perhaps an avant-garde installation, a work that lays bare the place of women in rock’n’roll by using the language of that form. Songs like “Fuck And Run” and “Flower” (with its notorious promise to “be your blowjob queen”) cast men with big sticks as the objects of her rock’n’roll lust. Perhaps that’s why Guyville sounds so rich and even exciting 25 years after its release and 10 years after its last reissue. It doesn’t just align itself with the #MeToo movement or against the sexual predator America elected to its highest office. More crucially, it offers a possible strategy by which women might combat such inequity through art and music.

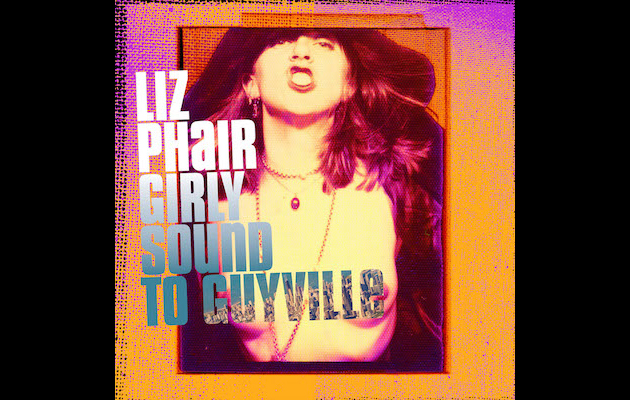

Perhaps the most notable aspect of this reissue of Guyville is the fact that it’s not really a reissue of Guyville. By gathering all these early recordings into one place for the first time, Girly-Sound To Guyville is something much more revealing than an anniversary commemoration. It’s a document of an artist finding and raising her voice: a souvenir from an era that questions long-held assumptions about the sex and the business of rock’n’roll.