When Judee Sill died in 1979 at the age of 35, she left behind a slim catalogue of songs that went underappreciated during her lifetime but now seem as sublime as anything else by her fabled generation of LA singer/songwriters. What Sill didn’t leave behind was much of a visual record. Given that ...

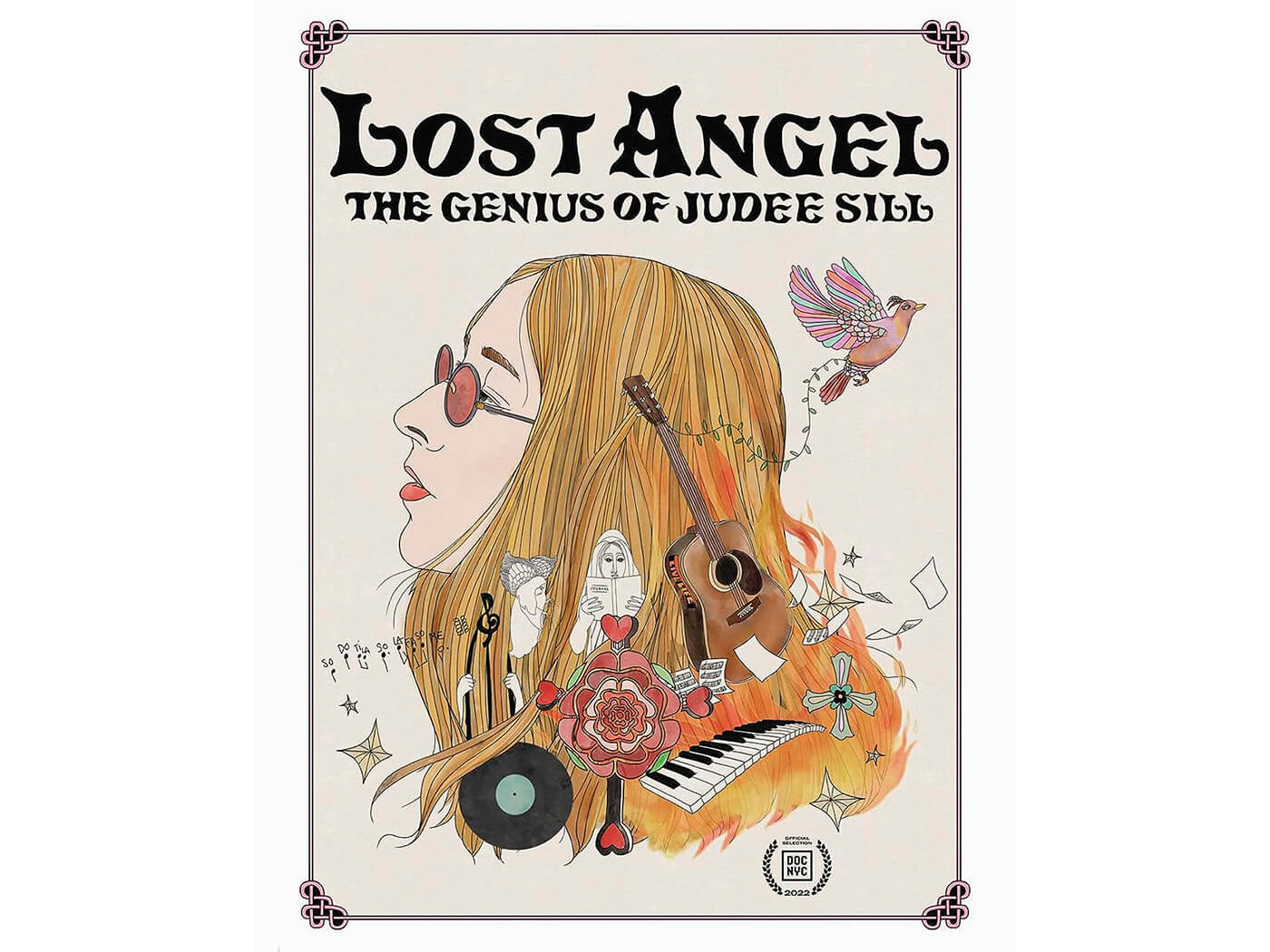

When Judee Sill died in 1979 at the age of 35, she left behind a slim catalogue of songs that went underappreciated during her lifetime but now seem as sublime as anything else by her fabled generation of LA singer/songwriters. What Sill didn’t leave behind was much of a visual record. Given that scant supply of surviving material – for example, grainy black-and-white footage of an outdoor concert in 1973, a performance for The Old Grey Whistle Test – a documentary portrait of Sill was always going to be a tough proposition. Yet in making Lost Angel: The Genius Of Judee Sill, directors Andy Brown and Brian Lindstrom find ways to overcome those limitations and create something that attains the same grace and beauty heard in Sill’s music.

Their most effective means turns out to be Sill’s own writings and drawings. Occasionally peppered with colorful language (“FUCK FORMULAS”) and read aloud by a Sill sound-alike, her journal entries, lyrics and notes for arrangements become a compelling visual representation of her inner life as well as a route into her increasingly complex music. Likewise, her illustrations become the basis for animations that variously evoke the old-west mythos of Sill explored in “Ridge Rider” and the free-flowing fusion of the spiritual and the sexual in “The Kiss”.

Rich with the most intimate and transcendent qualities of Sill’s music, these passages also provide a respite from the film’s more rudimentary aspects — and from the hardship that clearly filled Sill’s time in the world. The early death of her beloved father led to a more abusive situation in her childhood, prompting the teenaged Sill to dabble in drugs and even armed robbery before a spell in reform school. Immersing herself in church music while in the care of the state, she discovered another form that she’d eventually merge with her interests in jazz bass and Bach.

By the time Sill started earning notice for her songs by the late ‘60s, she’d already been through two marriages and several stints of heroin addiction. But there were plenty of people in LA’s music community who recognized how special she was. The film’s roster of friends and collaborators sharing their memories includes Graham Nash, Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne, Asylum boss David Geffen and her on-and-off-again beau J.D. Souther. Amusingly, the last is one of several former flames who believed they inspired Sill to write “The Ridge Rider”. Geffen takes this opportunity to counter the charge that Asylum’s lack of support doomed Sill’s two albums for the label, 1971’s Judee Sill and 1973’s astonishing Heart Food. He also does his best to quash the rumours that Sill disparaged him with a homophobic insult while onstage and then camped out on his lawn in an act of contrition. (“I didn’t even have a lawn,” he says.)

The litany of Sill’s misfortunes continued with the neck and back injuries – initially caused by a car wreck though there’s talk of the boyfriend who pushed her down the stairs – that left her in near-constant pain. Her condition exacerbated her drug problems, the effects of which discernible in her increasingly ragged handwriting as she nears her final journal entry.

Brown and Lindstrom find another vivid means of conveying Sill’s artistry and impact via the participation of a younger generation of musicians who sought to occupy – in the words of Weyes Blood’s Natalie Mering — “a more cosmic space”. The documentary’s also bracketed by different and equally captivating performances of “The Kiss” by Fleet Foxes and Big Thief’s Adrianne Lenker. “It seemed like a bottomless well,” says Lenker, “a life-giving song.” The description applies equally well to so much of what Sill was able to create and what the film presents so vividly, all without depriving her music of its mysteries.