Six disc document of Bolan's evolution... The treasure trove of classic rock material recorded for the BBC has become a key part of the vintage reissue catalogue. But few artists possessed a destiny so intertwined with Auntie Beeb that it could produce a six-CD box set. As the excellent Mark Paytress liner notes – designed to look like early ‘70s ‘inkie’ music press coverage – explain at length, this is largely down to the extraordinary relationship between former Stoke Newington mod Marc Feld and laconic Liverpudlian hippy music crusader John Peel, which coincided with the launch of Radio One in September 1967. Peel’s promotion of his androgynous, elfin, rockabilly-loving friend on the alternative margins of The BBC’s new pop channel was so persistent that, at one point on this fascinating set, Peel feels compelled to make an on-air denial of the rumours that he has a financial stake in Bolan’s success. Famously, the pair fell out abruptly and terminally as Bolan made the transition from underground purveyor of Tolkien-esque acoustic whimsy to pop star so huge that he invented a genre – glam-rock – and caused scenes of teen hysteria so uncontrolled that Britain’s tabloids routinely compared ‘T.Rextasy’ to Beatlemania. The music that made this phenomenon is all here. But what makes Marc Bolan At The BBC a great box set is that, through live shows, interviews and even oddly barbed announcements of T.Rex tracks, it tells the story of Bolan’s rise, fall and tragically terminated redemption in the manner of a good documentary. The first two discs document the struggle of an ambitious, prolific writer of inspired hippy gibberish to find an audience beyond a relatively small coterie of ‘freaks’. Discs three and four place the glory of one of the greatest rock ‘n’ roll noises ever created within the context of Bolan’s often startling hubris, pretentiousness and defensiveness when faced with an interviewer. And the final two discs chart a genuinely depressing creative decline, yet more hubris, increasing disrespect from BBC voices and the beginnings of a humble, self-mocking comeback before a car-crash at Barnes Common deprived us of a unique figure in British music. Whether this is the cunning agenda of compiler Clive Zone is unclear. But the story is so vivid that there’s absolutely no need for a narrator. For Bolan fans hungry for new music, the first two discs are the treasure trove. Kicking off with five tracks from Bolan’s strange Simon Napier-Bell-instigated stint as songwriter-guitarist with proto-punk troublemakers John’s Children, the abrupt switch just four months later to the mystical acoustica of the Tyrannosaurus Rex partnership with bongo player Steve Peregrine Took possesses a breathtaking chutzpah, and flags up Bolan’s ability to make abrupt U-turns that worked. Through sessions, concerts and even a poetry recital or two, the base Bolan elements take shape and coalesce into something increasingly special; the rockabilly themes of cars and girls reinterpreted through a personal mythology of meetings with wizards and bucolic imagery, with the generation gap between square adults and The Kids presented as a kind of metaphorical netherworld; a Middle-Earth of star-children prancing carefree to the funky strums and crackling vocals of Pied Piper Marc. By the time Mickey Finn replaced Took in late 1969, electric guitar is making its first tentative appearance, and songs like “Fist Heart Mighty Dawn Dart” and “By The Light Of The Magical Moon” are becoming a new kind of pop music, reaching for the James Burton licks, proper drums and Tolkien-meets-Little Richard teen poetry that finally changed everything for Bolan with the success of the “Ride A White Swan” single in October 1970. Many of the tracks covering the 1971-72 imperial phase here are simply the Tony Visconti-produced studio backing tracks with Bolan overdubbing new guitar and vocals. They show off what a pro Bolan was in even the most rudimentary studio situation, but, in the end, just sound like more sonically muffled versions of the superior originals. It’s the interviews that become increasingly fascinating, as even the most friendly question about the possibility that Bolan has lost the support of his underground audience is met with increasingly lofty pronouncements where he compares himself to Dylan and Hendrix, defines himself as a best-selling poet, suggests that both critics and old fans are too thick to understand the complex political messages hidden in lines like “She’s faster than most and she lives on the coast, uh-huh-huh.” Marc Bolan At The BBC lays this story bare, and, as well as thrilling you with at least four discs-worth of great music, feels like the most poignant release of Bolan’s posthumous career; a sad, frustrating unmade movie about a doomed rock star. But the soundtrack is a thriller. Garry Mulholland Q&A BOB HARRIS How did you first meet Bolan? It was at John Peel’s basement flat in Fulham in late 1967. I went round to interview John for a student magazine called Unit, so I was meeting him for the first time, too. Marc looked amazing, with his corkscrew hair and silk trousers, sitting on the carpet cross-legged strumming an acoustic guitar. It was the trigger moment for a great friendship with both of them. You went on to compere throughout the legendary T.Rextasy tour in early 1971… Yes. It was bedlam. At the first gig in Portsmouth there were hundreds of kids waiting outside afterwards. We went out through this corridor formed by policemen and all the girls were waving scissors around, trying to get locks of Marc’s hair. I was behind him so the blades of these scissors were coming at me at exactly eye-level. It was completely unexpected for Marc but very exciting. For the rest of the tour we were in the cars and gone while the last note was still resonating. Was the sudden change from cult-hippy Tyrannosaurus Rex to teen-glam T. Rex contrived ambition or natural progression? A combination of the two. The most important element was that Marc’s music was always underpinned by his enormous love for and knowledge of early rock ‘n’ roll. You get to “Ride A White Swan” – the turning point – and its exactly halfway between what “Deborah” was and what “Get It On” was going to become.’ The Bolan At The Beeb booklet reveals your take on the abrupt end of the Bolan/Peel relationship. Maybe it wasn’t Marc’s hubris after all… No. John wrote a hurtful review of T.Rex in Disc And Music Echo magazine. But John had a track record of doing this. Not long after I started on Whistle Test in 1970 he stopped talking to me, and didn’t until I started doing the country show on Radio 2 in 1998. He never explained why. INTERVIEW: GARRY MULHOLLAND

Six disc document of Bolan’s evolution…

The treasure trove of classic rock material recorded for the BBC has become a key part of the vintage reissue catalogue. But few artists possessed a destiny so intertwined with Auntie Beeb that it could produce a six-CD box set. As the excellent Mark Paytress liner notes – designed to look like early ‘70s ‘inkie’ music press coverage – explain at length, this is largely down to the extraordinary relationship between former Stoke Newington mod Marc Feld and laconic Liverpudlian hippy music crusader John Peel, which coincided with the launch of Radio One in September 1967. Peel’s promotion of his androgynous, elfin, rockabilly-loving friend on the alternative margins of The BBC’s new pop channel was so persistent that, at one point on this fascinating set, Peel feels compelled to make an on-air denial of the rumours that he has a financial stake in Bolan’s success.

Famously, the pair fell out abruptly and terminally as Bolan made the transition from underground purveyor of Tolkien-esque acoustic whimsy to pop star so huge that he invented a genre – glam-rock – and caused scenes of teen hysteria so uncontrolled that Britain’s tabloids routinely compared ‘T.Rextasy’ to Beatlemania.

The music that made this phenomenon is all here. But what makes Marc Bolan At The BBC a great box set is that, through live shows, interviews and even oddly barbed announcements of T.Rex tracks, it tells the story of Bolan’s rise, fall and tragically terminated redemption in the manner of a good documentary.

The first two discs document the struggle of an ambitious, prolific writer of inspired hippy gibberish to find an audience beyond a relatively small coterie of ‘freaks’. Discs three and four place the glory of one of the greatest rock ‘n’ roll noises ever created within the context of Bolan’s often startling hubris, pretentiousness and defensiveness when faced with an interviewer. And the final two discs chart a genuinely depressing creative decline, yet more hubris, increasing disrespect from BBC voices and the beginnings of a humble, self-mocking comeback before a car-crash at Barnes Common deprived us of a unique figure in British music. Whether this is the cunning agenda of compiler Clive Zone is unclear. But the story is so vivid that there’s absolutely no need for a narrator.

For Bolan fans hungry for new music, the first two discs are the treasure trove. Kicking off with five tracks from Bolan’s strange Simon Napier-Bell-instigated stint as songwriter-guitarist with proto-punk troublemakers John’s Children, the abrupt switch just four months later to the mystical acoustica of the Tyrannosaurus Rex partnership with bongo player Steve Peregrine Took possesses a breathtaking chutzpah, and flags up Bolan’s ability to make abrupt U-turns that worked. Through sessions, concerts and even a poetry recital or two, the base Bolan elements take shape and coalesce into something increasingly special; the rockabilly themes of cars and girls reinterpreted through a personal mythology of meetings with wizards and bucolic imagery, with the generation gap between square adults and The Kids presented as a kind of metaphorical netherworld; a Middle-Earth of star-children prancing carefree to the funky strums and crackling vocals of Pied Piper Marc.

By the time Mickey Finn replaced Took in late 1969, electric guitar is making its first tentative appearance, and songs like “Fist Heart Mighty Dawn Dart” and “By The Light Of The Magical Moon” are becoming a new kind of pop music, reaching for the James Burton licks, proper drums and Tolkien-meets-Little Richard teen poetry that finally changed everything for Bolan with the success of the “Ride A White Swan” single in October 1970.

Many of the tracks covering the 1971-72 imperial phase here are simply the Tony Visconti-produced studio backing tracks with Bolan overdubbing new guitar and vocals. They show off what a pro Bolan was in even the most rudimentary studio situation, but, in the end, just sound like more sonically muffled versions of the superior originals. It’s the interviews that become increasingly fascinating, as even the most friendly question about the possibility that Bolan has lost the support of his underground audience is met with increasingly lofty pronouncements where he compares himself to Dylan and Hendrix, defines himself as a best-selling poet, suggests that both critics and old fans are too thick to understand the complex political messages hidden in lines like “She’s faster than most and she lives on the coast, uh-huh-huh.”

Marc Bolan At The BBC lays this story bare, and, as well as thrilling you with at least four discs-worth of great music, feels like the most poignant release of Bolan’s posthumous career; a sad, frustrating unmade movie about a doomed rock star. But the soundtrack is a thriller.

Garry Mulholland

Q&A

BOB HARRIS

How did you first meet Bolan?

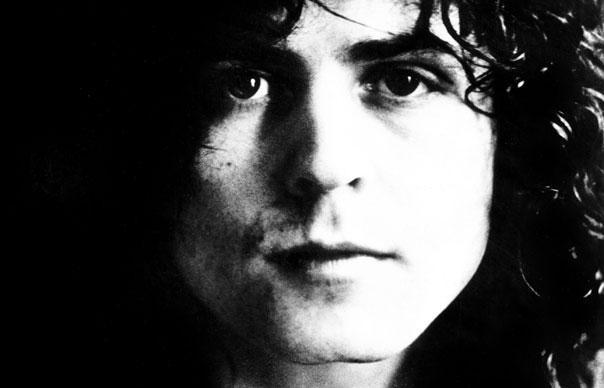

It was at John Peel’s basement flat in Fulham in late 1967. I went round to interview John for a student magazine called Unit, so I was meeting him for the first time, too. Marc looked amazing, with his corkscrew hair and silk trousers, sitting on the carpet cross-legged strumming an acoustic guitar. It was the trigger moment for a great friendship with both of them.

You went on to compere throughout the legendary T.Rextasy tour in early 1971…

Yes. It was bedlam. At the first gig in Portsmouth there were hundreds of kids waiting outside afterwards. We went out through this corridor formed by policemen and all the girls were waving scissors around, trying to get locks of Marc’s hair. I was behind him so the blades of these scissors were coming at me at exactly eye-level. It was completely unexpected for Marc but very exciting. For the rest of the tour we were in the cars and gone while the last note was still resonating.

Was the sudden change from cult-hippy Tyrannosaurus Rex to teen-glam T. Rex contrived ambition or natural progression?

A combination of the two. The most important element was that Marc’s music was always underpinned by his enormous love for and knowledge of early rock ‘n’ roll. You get to “Ride A White Swan” – the turning point – and its exactly halfway between what “Deborah” was and what “Get It On” was going to become.’

The Bolan At The Beeb booklet reveals your take on the abrupt end of the Bolan/Peel relationship. Maybe it wasn’t Marc’s hubris after all…

No. John wrote a hurtful review of T.Rex in Disc And Music Echo magazine. But John had a track record of doing this. Not long after I started on Whistle Test in 1970 he stopped talking to me, and didn’t until I started doing the country show on Radio 2 in 1998. He never explained why.

INTERVIEW: GARRY MULHOLLAND