Soulful debut is stunning introduction to producer's talents... It opens with a song with no intro. It’s a love song called “One Of These Days”, and its one of those songs where the intensity of the lyrics is undercut by the contemplative hush of the music, and the humble, diffident voice of a new artist called Matthew E. White. White is not a singer or songwriter by trade. He is a 29-year-old session musician, producer and arranger who decided to make an album to showcase his dream baby: a self-contained label, studio and house band called Spacebomb. So the entire arsenal gathered by White’s years of experience and expertise is at his disposal on “One Of These Days”: three-piece rhythm section, eight horn players, nine string players, a choir. Yet the anticipated wall-of-noise never emerges, and the song creeps around the mind, unveiling each new layer of texture with almost subliminal softness, reveling in the contrast between the minor key dread of the verse, and the comforting major key of the chorus. And what gradually unveils here is a dark devotion that starkly contrasts with the avuncular, country-soul mumble of the soundtrack: “I don’t want to live a minute longer than you/So let’s meet the Lord together” hits like a southern Baptist twist on Morrissey’s melodramatic death wishes on The Smiths’ “There Is A Light That Never Goes Out”. And of course, when love is that nihilistic, it turns out that the object of White’s desire is long gone. Glory fades, flowers die, and White asks, with sighing tenderness, “Why aren’t you still standing, on the sidewalk, by my stairs?/Seems like everyone’s moving away.” Carbon-based lifeforms. Chelsea managers. Love. In this world, nothing is permanent. The song is the perfect way into Big Inner, a cute pun from a big fan of The Band, and a beautiful album of loss and grief smuggled under cover of a sound like quiet sunny Sundays and a whispered conversation with a shy friend. The seven songs explore faith, death, home comforts and getting dumped and, although Big Inner is no concept album, its immaculate remodelling of turn of the ‘70s blue-eyed soul in the tradition of Tony Joe White, Carole King, Laura Nyro and White favourite Jackie DeShannon invites you into a song suite of sustained mood that is not designed for iPod on shuffle mode. At various points it reminds you of Lambchop, Astral Weeks and Shuggie Otis. White and his arrangers Phil Cook (choir) and Trey Pollard (strings and horns) paint like minimalists despite allowing themselves the most colourful palette available. And while White is no soul singer in the accepted sense, his humble mumbles, strained falsettos and double-tracked whispers lend intimacy to a meticulously played and arranged music which, if led by a more technical voice, could have wandered into blander territory. Instead, each riff, lick, melody and harmony is pitched for maximum effect from minimum bluster, an exquisite exercise in quiet storm economy. “Big Love” follows “One Of These Days” with the closest Big Inner comes to big funk, as shuffling drums and gospel piano backdrop a kiss-off to a faithless lover. As the choir rise into full-on Rotary Connection ecstasy, there’s something of Bill Callahan’s wry stoicism in the way White declares: “I am a barracuda/I am a hurricane” in a voice so small and modest that minnows and summer breezes would appear more appropriate symbols of White’s independence. It’s an ironically defiant stance appropriately undercut by “Will You Love Me”, which slows the central melody of Joe South’s “Games People Play” to a desolate crawl as White begs, one suspects, the same lover to deliver him from an aching loneliness. “Gone Away” grieves for a dead child like a Stax ballad with all the bluesy assertiveness sucked into a black hole of hollow-eyed resignation. The darkness is lifted by the swamp-funk playfulness of “Steady Pace”, which wonders out loud “where the night spends all it’s days” and implores us to slow down and wallow in each moment that we might be lucky enough to be in love. “Hot Toddies”, yet another beautiful, soulful ballad balanced between brassy, honky-tonk funk and a sophistication of orchestral arrangement that Van Dyke Parks would be proud of, continues to gently push a theme of love as home comfort rather than breathless thrill… until you realise that the lover here is booze, as White murmurs his acquiescence to the devil’s “sweet whiskey”. It’s all building towards the album’s final moment of catharsis, a five-minute exaltation based around lines lifted from Brazilian legend Jorge Ben’s “Brother”: “Jesus Christ is our Lord/Jesus Christ, He is your friend.” It’s the coda of closing song “Brazos”, which is about slavery, faith and the doubt that surrounds belief when you are trying to endure Hell on Earth. The euphoric coda captures the ecstasy of joy derived from fervent belief in Heaven and a better place, with a spine-tingling dynamic based on adding simple elements – a new counter-melody here, a handclap there - until the song becomes the kind of exultant rave-up that Primal Scream wished that they’d achieved on Screamadelica. But White is as loaded with doubt as the Apostle Peter: “Sunk like a stone because he wasn’t a believer… And I’m not sure that I am either.” White is a child of devout Christian missionaries, and “Brazos” is as cathartic, mesmeric and profoundly moving as a man’s quest to resolve his spiritual doubts ought to be. Big Inner exists primarily because White wanted to spread the gospel of his Spacebomb label. But the guy with the big vision and the small voice may have unwittingly screwed up. He’s made one of the great albums of modern Americana, and one suspects that a reluctant star is born. Spacebomb as the new Stax may have to wait. Garry Mulholland Q&A Matthew E. White Why so long to make your first album? It took me a while to get the musical chops together to make a record like this. You need a certain amount of experience in leading sessions and getting that many people together in a room, as well as writing the music. And from a songwriting perspective, it took me a while to find my voice. Its not like when I was 20 I said, “I’m gonna make a record when I’m 28.” But this record is also a way to showcase what the Spacebomb label can do. So - what can the Spacebomb label do? I live in an amazing community here in Richmond, Virginia. It has lots of wonderful musicians. So I had this idea about doing things the old way; you know, having a house band. I want people to come here and make records. I thought I should be the first one to do it because I was the most familiar with the process of making records and it’s my vision. And then if it all turned out shitty then I’m the guy who bears the weight. We made this record in seven days and unbelievably cheaply. This idea works. And one of the big reasons for me to found Spacebomb is so I can make more than one record a year with a variety of artists. Would you describe Big Inner as a blue-eyed soul album? Short answer… yeah. But it gives me a little too much credit as a singer! But one of the things I like about the record is that, as a producer and arranger, I’m very professional. I do that for a living. But there are parts of Big Inner which are raw and wild and I don’t really know what I’m doing. One of those parts is the songwriting, and the other is the singing. No one would ask me to sing unless I’m in charge. I’m really aware of that and it doesn’t bother me. It works. The album gives co-songwriting credits to Latin great Jorge Ben, gospel artist Washington Phillips and reggae man Jimmy Cliff. But you haven’t sampled them… I just wanted to be very clear in the credits that I wasn’t trying to do a George Harrison “My Sweet Lord” thing! The chorus to “Will You Love Me”, is pulled straight from Cliff’s “Many Rivers To Cross”. The chorus of Brazos is from “Brother” by Jorge Ben. There are elements of “What Are You Doing In Heaven Today” by Washington Philips throughout “Gone Away”. My publishers don’t really like that I credit like that! But those three artists and the traditions that they represent are incredibly important to me and I don’t want to try and sweep that under the rug. Your parents are Christian missionaries. How has that affected your art? I spent four years in Manila in The Philippines as a child. We were out there during the coup in the ‘80s and there were tanks turning round in my driveway, which to me, as a little boy, was awesome because I didn’t know what that meant. I went to cockfights. Being there and coming back to America made my idea of what is American more three-dimensional than people who have always been here. As for religious faith, its something I’m still dealing with in terms of what it means to me. There are some things about faith that I don’t like. But it’s been a big part of my life and my past so it’s honest of me to draw upon that for my songs. Is it true that “Gone Away” was inspired by the death of a cousin? Yes. She was killed in a car accident in October 2010. She was just four years old. I’d been out at a bar when I heard and I pretty much picked up a guitar and wrote the song right there. I was just trying to make sense of it. INTERVIEW: GARRY MULHOLLAND

Soulful debut is stunning introduction to producer’s talents…

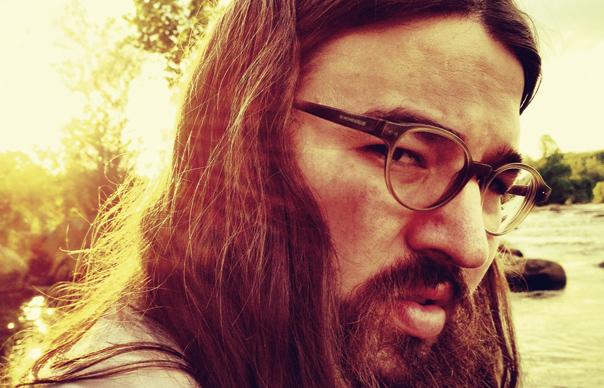

It opens with a song with no intro. It’s a love song called “One Of These Days”, and its one of those songs where the intensity of the lyrics is undercut by the contemplative hush of the music, and the humble, diffident voice of a new artist called Matthew E. White.

White is not a singer or songwriter by trade. He is a 29-year-old session musician, producer and arranger who decided to make an album to showcase his dream baby: a self-contained label, studio and house band called Spacebomb. So the entire arsenal gathered by White’s years of experience and expertise is at his disposal on “One Of These Days”: three-piece rhythm section, eight horn players, nine string players, a choir.

Yet the anticipated wall-of-noise never emerges, and the song creeps around the mind, unveiling each new layer of texture with almost subliminal softness, reveling in the contrast between the minor key dread of the verse, and the comforting major key of the chorus. And what gradually unveils here is a dark devotion that starkly contrasts with the avuncular, country-soul mumble of the soundtrack: “I don’t want to live a minute longer than you/So let’s meet the Lord together” hits like a southern Baptist twist on Morrissey’s melodramatic death wishes on The Smiths’ “There Is A Light That Never Goes Out”. And of course, when love is that nihilistic, it turns out that the object of White’s desire is long gone. Glory fades, flowers die, and White asks, with sighing tenderness, “Why aren’t you still standing, on the sidewalk, by my stairs?/Seems like everyone’s moving away.” Carbon-based lifeforms. Chelsea managers. Love. In this world, nothing is permanent.

The song is the perfect way into Big Inner, a cute pun from a big fan of The Band, and a beautiful album of loss and grief smuggled under cover of a sound like quiet sunny Sundays and a whispered conversation with a shy friend. The seven songs explore faith, death, home comforts and getting dumped and, although Big Inner is no concept album, its immaculate remodelling of turn of the ‘70s blue-eyed soul in the tradition of Tony Joe White, Carole King, Laura Nyro and White favourite Jackie DeShannon invites you into a song suite of sustained mood that is not designed for iPod on shuffle mode. At various points it reminds you of Lambchop, Astral Weeks and Shuggie Otis.

White and his arrangers Phil Cook (choir) and Trey Pollard (strings and horns) paint like minimalists despite allowing themselves the most colourful palette available. And while White is no soul singer in the accepted sense, his humble mumbles, strained falsettos and double-tracked whispers lend intimacy to a meticulously played and arranged music which, if led by a more technical voice, could have wandered into blander territory. Instead, each riff, lick, melody and harmony is pitched for maximum effect from minimum bluster, an exquisite exercise in quiet storm economy.

“Big Love” follows “One Of These Days” with the closest Big Inner comes to big funk, as shuffling drums and gospel piano backdrop a kiss-off to a faithless lover. As the choir rise into full-on Rotary Connection ecstasy, there’s something of Bill Callahan’s wry stoicism in the way White declares: “I am a barracuda/I am a hurricane” in a voice so small and modest that minnows and summer breezes would appear more appropriate symbols of White’s independence. It’s an ironically defiant stance appropriately undercut by “Will You Love Me”, which slows the central melody of Joe South’s “Games People Play” to a desolate crawl as White begs, one suspects, the same lover to deliver him from an aching loneliness.

“Gone Away” grieves for a dead child like a Stax ballad with all the bluesy assertiveness sucked into a black hole of hollow-eyed resignation. The darkness is lifted by the swamp-funk playfulness of “Steady Pace”, which wonders out loud “where the night spends all it’s days” and implores us to slow down and wallow in each moment that we might be lucky enough to be in love. “Hot Toddies”, yet another beautiful, soulful ballad balanced between brassy, honky-tonk funk and a sophistication of orchestral arrangement that Van Dyke Parks would be proud of, continues to gently push a theme of love as home comfort rather than breathless thrill… until you realise that the lover here is booze, as White murmurs his acquiescence to the devil’s “sweet whiskey”.

It’s all building towards the album’s final moment of catharsis, a five-minute exaltation based around lines lifted from Brazilian legend Jorge Ben’s “Brother”: “Jesus Christ is our Lord/Jesus Christ, He is your friend.” It’s the coda of closing song “Brazos”, which is about slavery, faith and the doubt that surrounds belief when you are trying to endure Hell on Earth. The euphoric coda captures the ecstasy of joy derived from fervent belief in Heaven and a better place, with a spine-tingling dynamic based on adding simple elements – a new counter-melody here, a handclap there – until the song becomes the kind of exultant rave-up that Primal Scream wished that they’d achieved on Screamadelica. But White is as loaded with doubt as the Apostle Peter: “Sunk like a stone because he wasn’t a believer… And I’m not sure that I am either.” White is a child of devout Christian missionaries, and “Brazos” is as cathartic, mesmeric and profoundly moving as a man’s quest to resolve his spiritual doubts ought to be.

Big Inner exists primarily because White wanted to spread the gospel of his Spacebomb label. But the guy with the big vision and the small voice may have unwittingly screwed up. He’s made one of the great albums of modern Americana, and one suspects that a reluctant star is born. Spacebomb as the new Stax may have to wait.

Garry Mulholland

Q&A

Matthew E. White

Why so long to make your first album?

It took me a while to get the musical chops together to make a record like this. You need a certain amount of experience in leading sessions and getting that many people together in a room, as well as writing the music. And from a songwriting perspective, it took me a while to find my voice. Its not like when I was 20 I said, “I’m gonna make a record when I’m 28.” But this record is also a way to showcase what the Spacebomb label can do.

So – what can the Spacebomb label do?

I live in an amazing community here in Richmond, Virginia. It has lots of wonderful musicians. So I had this idea about doing things the old way; you know, having a house band. I want people to come here and make records. I thought I should be the first one to do it because I was the most familiar with the process of making records and it’s my vision. And then if it all turned out shitty then I’m the guy who bears the weight. We made this record in seven days and unbelievably cheaply. This idea works. And one of the big reasons for me to found Spacebomb is so I can make more than one record a year with a variety of artists.

Would you describe Big Inner as a blue-eyed soul album?

Short answer… yeah. But it gives me a little too much credit as a singer! But one of the things I like about the record is that, as a producer and arranger, I’m very professional. I do that for a living. But there are parts of Big Inner which are raw and wild and I don’t really know what I’m doing. One of those parts is the songwriting, and the other is the singing. No one would ask me to sing unless I’m in charge. I’m really aware of that and it doesn’t bother me. It works.

The album gives co-songwriting credits to Latin great Jorge Ben, gospel artist Washington Phillips and reggae man Jimmy Cliff. But you haven’t sampled them…

I just wanted to be very clear in the credits that I wasn’t trying to do a George Harrison “My Sweet Lord” thing! The chorus to “Will You Love Me”, is pulled straight from Cliff’s “Many Rivers To Cross”. The chorus of Brazos is from “Brother” by Jorge Ben. There are elements of “What Are You Doing In Heaven Today” by Washington Philips throughout “Gone Away”. My publishers don’t really like that I credit like that! But those three artists and the traditions that they represent are incredibly important to me and I don’t want to try and sweep that under the rug.

Your parents are Christian missionaries. How has that affected your art?

I spent four years in Manila in The Philippines as a child. We were out there during the coup in the ‘80s and there were tanks turning round in my driveway, which to me, as a little boy, was awesome because I didn’t know what that meant. I went to cockfights. Being there and coming back to America made my idea of what is American more three-dimensional than people who have always been here. As for religious faith, its something I’m still dealing with in terms of what it means to me. There are some things about faith that I don’t like. But it’s been a big part of my life and my past so it’s honest of me to draw upon that for my songs.

Is it true that “Gone Away” was inspired by the death of a cousin?

Yes. She was killed in a car accident in October 2010. She was just four years old. I’d been out at a bar when I heard and I pretty much picked up a guitar and wrote the song right there. I was just trying to make sense of it.

INTERVIEW: GARRY MULHOLLAND