Bloomfield is God? Long-overdue, career-spanning look at rock's foremost guitar trailblazer... Michael Bloomfield (affectionately: Bloomers) lit up the ‘60s. A guitarist of indomitable power and grace, an effervescent personality, a maestro likely to astound in virtually any environment, any genre, he was a shape-shifter, a transformer, an architect and an archetype—the original rock guitar superhero. Like flipping a switch, he could accelerate from sweetness to fury and back again in the blink of an eye. “At times,” remembers his friend and bandmate Barry Goldberg, “his solos would be like bombs going off.” As the blazing experimentalism and sense of discovery of the 1960s faded into the genre-codified, corporate rock of the '70s, the legend of Bloomfield's mind-melting guitar prowess could be felt and heard everywhere—in post-psychedelic San Francisco, in the distorted, cartoonish blues riffs of proto metal bands and arena rockers, in the playing of Eric Clapton, Carlos Santana, Jeff Beck, and, later, a Texas kid named Stevie Ray Vaughan. All of which, strangely enough, was anathema to Bloomfield himself. His high points are unassailable: Backing virtually every significant bluesman, from Sleepy John Estes to Muddy Waters; lynchpin of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the interracial juggernaut that helped transform “pop” from shallow teenybopper fluff to serious “rock”. He accompanied Bob Dylan on his most momentous, gig ever—Newport 1965; spun out trippy, mesmerizing guitar on Al Kooper’s smash-hit Super Session. His low points are, sadly enough, unassailable too, including quarter-hearted ‘70s supergroup projects, a nasty heroin habit, and a kind of self-imposed exile. Decades in the making, curated by friend and frequent collaborator Kooper, Head Heart Hands collects 46 tracks, a dozen previously unreleased, abetted by a fine hour-long documentary—Sweet Blues—directed by Bob Sarles, which, through many interviews, captures some of the essence of the man. Less an authoritative scouring of the vaults, more of—as noted—a scrapbook, it supplements a discography that is as scattered and discordant as a typical Bloomfield guitar lead is fluid and pure. The set begins at New York’s Columbia Studios, Bloomfield auditioning for legendary producer John Hammond. He pours his heart into a sturdy acoustic blues, “I’m a Country Boy,” delivering enough intricate guitar figures to virtually overwhelm the song, before sliding effortlessly into the country fingerpicking flash of “Hammond’s Rag,” a Merle Travis rip, an anomaly, a fairly shocking one at that, in the Bloomfield repertoire. Hardcore blues, though, as filtered through the postwar generation of electrified giants like Waters, Wolf, and Williamson, was Bloomfield’s lifelong passion, and virtually his entire dossier reflects it. Standards like “I Got My Mojo Workin’” (a later Hammond demo) and “Born in Chicago” (embryonic, exhilarating Butterfield) are emblematic and revelatory, auguring a new, heavier, high-octane normal as rock merges with blues circa 1965-66. By the time of his 1968 improvisatory LP with Kooper and Stephen Stills — Super Session — Bloomfield’s approach had evolved ever so slightly. “Albert’s Shuffle,” a highlight, is typical—pure unsullied blues structures, but with notes twisted, stretched, battered, and bruised amid a sly mix of vibrato and sustain, draped over familiar rhythms, cut to fit any (usually dark) mood. “Stop,” a workout of Howard Tate’s soul smash, is even better, Bloomfield freewheeling, shooting out the lights and sparring with some electrifying Kooper’s stutter-step organ fills. Within easy hindsight, three-plus decades on from his sad death at just 37, one can sense that Bloomfield was boxed in, by audience expectations, by drug use and declining health, and by a blues purist’s self-imposed limitations. Never a great (or confident) singer, nor a particularly committed songwriter (though he had his moments), his expertise was in interpretation and embellishment, and as a classic ensemble player and ambassador, passionate in bringing substance, foundation, and a jazzman’s gravitas to an oftentimes ethereal pop world. Conversely, the more Bloomfield was challenged, the more he produced work of immense emotional intensity and stunning complexity. Instructed by Dylan on Highway 61 Revisited to avoid “any B.B. King shit,” he instinctively invented a new sonic language, reeling off stinging leads and fills of coruscating power. Head Heart Hands picks up two heretofore unreleased pieces therefrom, a mesmerizing instrumental run-through of “Like A Rolling Stone,” and a rare version of the incomparable “Tombstone Blues,” the Chambers Brothers on backing vocals, Bloomfield’s raw, caustic guitar dancing darkly, forcefully around Dylan’s every verse. The splendiferous Butterfield Band opus “East-West” is Bloomfield’s crown jewel, and one of the most audacious pieces of music produced in the pop pantheon. Blindingly ambitious, pushing boundaries at every level, it begins on a bluesy, cascading plane, but soon swerves—traditional musical structures melting in a fiery 13-minute rage of raga and eastern modalities, straight R&B, free jazz, classic pop, and back again, Bloomfield’s guitar set to stun. Though others were toying with this worldly fusion, Coltrane-meets-Shankar territory in the mid-60s, including the Byrds on “Eight Miles High”, one might easily argue that the preeminent aesthetic of “East-West”, especially when taken up by legions of west-coasters, ignited the psychedelic movement. That Bloomfield toyed with but never truly returned to its lofty heights is a shame, and one of his darker mysteries. The Electric Flag was, potentially, even more revolutionary. Envisioned by Bloomfield — shades of Gram Parsons — as a repository for “all kinds of American music,” the group had flashes of brilliance, like a delirious, horn-driven swing through Howlin’ Wolf’s “Killing Floor,” as well as its emotional flipside, the subtle, oh-so-brief “Easy Rider.” But personality struggles, lack of strong original material, and, eventually, an appetite for hard drugs, did them in. Head Heart Hands adds a couple solid live Flag cuts and a generous section studio/live tracks from the Super Session period, before heading into Bloomfield’s ‘70s wilderness with nearly an entire disc of latter-day live material. These complete the picture, but yawning gaps remain: Though the fledgling Flag might have best exhibited their early ambitions on the psychsploitation soundtrack The Trip, that period is ignored; so too are two exemplary albums with Butterfield/Flag alumni, where Bloomfield relished his backing role — Barry Goldberg’s Two Jews Blues and Nick Gravenites My Labors. Surprisingly, no live 1960s Dylan material appears either, though the set winds down with the oft-bootlegged “Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar”, Dylan at the Warfield 1980, Bloomfield riffing out turbo-charged monsters like it’s 1965 all over again. Luke Torn Q&A With the Electric Flag’s Barry Goldberg When did you first meet Michael? Well, you know, it goes way back, 16 years old, in high school. He was from the suburbs, I was from the city, and we had high school bands. Mike and I had a band called King Dennis and the Kingsmen. We would play Sweet 16 parties. Those were a big deal, because we’d make sure we were the only guys there. It was pretty much a rock and roll band, it wasn’t really a blues thing then. We’d cover the Ventures, Johnny and the Hurricanes, all those kinda early instrumental bands. When did Michael start checking out the blues scene? The south Side of Chicago might as well have been Russia or something, nobody ever went down there. Except Michael started going down there . . . playing on Maxwell Street, as early as 14, 15 years old, just playing on the street corners and the sidewalks. He did it because of his love and his passion for the blues. What do you most think attracted him most? It was a cultural thing … mystical. It wasn’t like rock and roll. You know, it unleashed certain things in our heads, our minds, and our souls, that rock and roll didn’t. It cast a spell. The great guitar players that Michael could listen to, because in rock and roll at that time, there wasn’t a Hendrix or anyone like a virtuoso guy. With the blues, Michael was into B. B. King, Otis Rush, Muddy Waters, and he wanted to learn, he also discovered the country blues thing, too—Blind Lemon [Jefferson] and all those people. He was playing both acoustic and electric in those days? Oh, yeah, along with the folk music. He was an MC at this coffeehouse on Rush Street, which was sort of like the bourbon Street of Chicago, and he would conduct those shows, and bring down all those guys from the south side and west side, like Big Joe Williams, to play for these college kids and introduce them to this whole other life. Like a switch was flipped? Went we down to a place called Silvio’s, where Howlin’ Wolf was playing, and I followed Michael in there. You know, he was my leader. He had that kind of personality—you would follow him into hell. You know, I loved him man. Later on we were inseparable. He inspired me. Did you see the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in their earliest days? I was actually asked to play keyboards in the Butterfield Band in Chicago. I did a couple of gigs with Paul, and Michael and Paul invited me to come to Newport [in 1965]. We got in the car, we drove to Rhode Island, when we got there, their producer, Paul Rothchild, said ‘I don’t hear keyboards with the band,’ and so that brought me right down. The Butterfield Band was a huge success, though. You were in the group for the Dylan set though... Michael introduced me to Bob. And Bob asked me to play keyboards. I was playing organ. I had known the song, “Like a Rolling Stone,” because Michael had brought home the demo from when he had done the sessions. I learned the changes, so that was ok. And we did “Maggie’s Farm.” And it was a controversial reaction—some people liking it and some feeling that Bob had betrayed them. Do you think Michael had a sense of the gravity of the moment? I thought he had a great time. Just smiling. And we were just on a mission, blazing through in the name of rock and roll. What was the reaction after the show that night? Well, we just did our thing. And of course, Bob was upset—I guess. But I thought at that moment that a new movement had been born—a new focus and a new direction in music, and it changed that thing forever. I understand Bloomfield was an ambassador for the blues in San Francisco, in the psych years? Yeah, he did that to return the favor. Later on, with the Electric Flag and when he played with Butterfield, he had a relationship with Bill Graham and he got Bill to book all these other acts. He said “Hey, they have agents, too.” You know, bring in Muddy, bring in Wolf, bring in B.B. King. Bill started doing that, and Michael was pretty much responsible for that. What was the blueprint of the Electric Flag? He was uncomfortable with the Butterfield Band, so he approached me to start the Electric Flag—he wanted to have an all-American music band, that could play every style of American music—from blues to Motown—and he liked that until it became on the verge of becoming a supergroup. What kind of a turning point was Monterey Pop? We premiered our first album, Long Time Comin’ there, and that was intense because all eyes were on us. Michael was freaked out by all of that. There was so much pressure on him because he was the leader of the band. His personality, his very intense personality, caught on fire, and consequently he couldn’t sleep. He couldn’t turn it off. And that was a part you could hear in his music, that made his music so special. No one ever had that intensity, that burning, in their playing. Unfortunately, it was a curse at the same time That led to the Electric Flag’s demise? To me, from the reaction of the crowd, we accomplished our goal, our mission. We had an above-average set, I think. After that, we had sorta like won the battle, won the war. We were on a course. And unfortunately, in those days, there were a lot of drugs around. Our manager tried to talk to us, ‘You know, hey man, if you guys just play it cool, you could retire at the age of 40.’ But we were on a different course, unfortunately, and let that get the best of us, and the band started to deteriorate. It became awful personality-wise. As Michael receded from the spotlight, do you think he was a misunderstood figure? He didn’t like the spotlight, he didn’t like the pressure. He had bad insomnia and he liked the comfort zone of his room. He didn’t really need the fame and glory, he shunned away from that. He was a private kind of guy. INTERVIEW: LUKE TORN

Bloomfield is God? Long-overdue, career-spanning look at rock’s foremost guitar trailblazer…

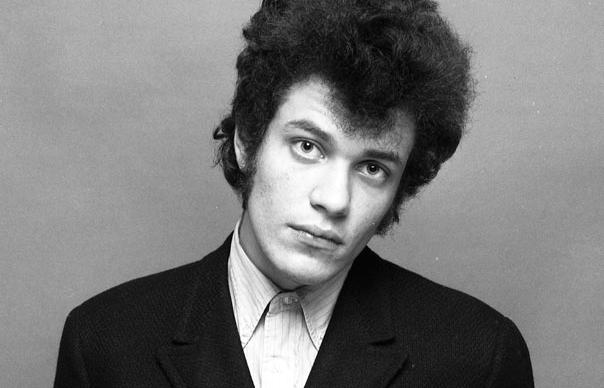

Michael Bloomfield (affectionately: Bloomers) lit up the ‘60s. A guitarist of indomitable power and grace, an effervescent personality, a maestro likely to astound in virtually any environment, any genre, he was a shape-shifter, a transformer, an architect and an archetype—the original rock guitar superhero. Like flipping a switch, he could accelerate from sweetness to fury and back again in the blink of an eye. “At times,” remembers his friend and bandmate Barry Goldberg, “his solos would be like bombs going off.”

As the blazing experimentalism and sense of discovery of the 1960s faded into the genre-codified, corporate rock of the ’70s, the legend of Bloomfield’s mind-melting guitar prowess could be felt and heard everywhere—in post-psychedelic San Francisco, in the distorted, cartoonish blues riffs of proto metal bands and arena rockers, in the playing of Eric Clapton, Carlos Santana, Jeff Beck, and, later, a Texas kid named Stevie Ray Vaughan. All of which, strangely enough, was anathema to Bloomfield himself.

His high points are unassailable: Backing virtually every significant bluesman, from Sleepy John Estes to Muddy Waters; lynchpin of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the interracial juggernaut that helped transform “pop” from shallow teenybopper fluff to serious “rock”. He accompanied Bob Dylan on his most momentous, gig ever—Newport 1965; spun out trippy, mesmerizing guitar on Al Kooper’s smash-hit Super Session. His low points are, sadly enough, unassailable too, including quarter-hearted ‘70s supergroup projects, a nasty heroin habit, and a kind of self-imposed exile.

Decades in the making, curated by friend and frequent collaborator Kooper, Head Heart Hands collects 46 tracks, a dozen previously unreleased, abetted by a fine hour-long documentary—Sweet Blues—directed by Bob Sarles, which, through many interviews, captures some of the essence of the man. Less an authoritative scouring of the vaults, more of—as noted—a scrapbook, it supplements a discography that is as scattered and discordant as a typical Bloomfield guitar lead is fluid and pure.

The set begins at New York’s Columbia Studios, Bloomfield auditioning for legendary producer John Hammond. He pours his heart into a sturdy acoustic blues, “I’m a Country Boy,” delivering enough intricate guitar figures to virtually overwhelm the song, before sliding effortlessly into the country fingerpicking flash of “Hammond’s Rag,” a Merle Travis rip, an anomaly, a fairly shocking one at that, in the Bloomfield repertoire.

Hardcore blues, though, as filtered through the postwar generation of electrified giants like Waters, Wolf, and Williamson, was Bloomfield’s lifelong passion, and virtually his entire dossier reflects it. Standards like “I Got My Mojo Workin’” (a later Hammond demo) and “Born in Chicago” (embryonic, exhilarating Butterfield) are emblematic and revelatory, auguring a new, heavier, high-octane normal as rock merges with blues circa 1965-66.

By the time of his 1968 improvisatory LP with Kooper and Stephen Stills — Super Session — Bloomfield’s approach had evolved ever so slightly. “Albert’s Shuffle,” a highlight, is typical—pure unsullied blues structures, but with notes twisted, stretched, battered, and bruised amid a sly mix of vibrato and sustain, draped over familiar rhythms, cut to fit any (usually dark) mood. “Stop,” a workout of Howard Tate’s soul smash, is even better, Bloomfield freewheeling, shooting out the lights and sparring with some electrifying Kooper’s stutter-step organ fills.

Within easy hindsight, three-plus decades on from his sad death at just 37, one can sense that Bloomfield was boxed in, by audience expectations, by drug use and declining health, and by a blues purist’s self-imposed limitations. Never a great (or confident) singer, nor a particularly committed songwriter (though he had his moments), his expertise was in interpretation and embellishment, and as a classic ensemble player and ambassador, passionate in bringing substance, foundation, and a jazzman’s gravitas to an oftentimes ethereal pop world.

Conversely, the more Bloomfield was challenged, the more he produced work of immense emotional intensity and stunning complexity. Instructed by Dylan on Highway 61 Revisited to avoid “any B.B. King shit,” he instinctively invented a new sonic language, reeling off stinging leads and fills of coruscating power. Head Heart Hands picks up two heretofore unreleased pieces therefrom, a mesmerizing instrumental run-through of “Like A Rolling Stone,” and a rare version of the incomparable “Tombstone Blues,” the Chambers Brothers on backing vocals, Bloomfield’s raw, caustic guitar dancing darkly, forcefully around Dylan’s every verse.

The splendiferous Butterfield Band opus “East-West” is Bloomfield’s crown jewel, and one of the most audacious pieces of music produced in the pop pantheon. Blindingly ambitious, pushing boundaries at every level, it begins on a bluesy, cascading plane, but soon swerves—traditional musical structures melting in a fiery 13-minute rage of raga and eastern modalities, straight R&B, free jazz, classic pop, and back again, Bloomfield’s guitar set to stun. Though others were toying with this worldly fusion, Coltrane-meets-Shankar territory in the mid-60s, including the Byrds on “Eight Miles High”, one might easily argue that the preeminent aesthetic of “East-West”, especially when taken up by legions of west-coasters, ignited the psychedelic movement. That Bloomfield toyed with but never truly returned to its lofty heights is a shame, and one of his darker mysteries.

The Electric Flag was, potentially, even more revolutionary. Envisioned by Bloomfield — shades of Gram Parsons — as a repository for “all kinds of American music,” the group had flashes of brilliance, like a delirious, horn-driven swing through Howlin’ Wolf’s “Killing Floor,” as well as its emotional flipside, the subtle, oh-so-brief “Easy Rider.” But personality struggles, lack of strong original material, and, eventually, an appetite for hard drugs, did them in.

Head Heart Hands adds a couple solid live Flag cuts and a generous section studio/live tracks from the Super Session period, before heading into Bloomfield’s ‘70s wilderness with nearly an entire disc of latter-day live material. These complete the picture, but yawning gaps remain: Though the fledgling Flag might have best exhibited their early ambitions on the psychsploitation soundtrack The Trip, that period is ignored; so too are two exemplary albums with Butterfield/Flag alumni, where Bloomfield relished his backing role — Barry Goldberg’s Two Jews Blues and Nick Gravenites My Labors. Surprisingly, no live 1960s Dylan material appears either, though the set winds down with the oft-bootlegged “Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar”, Dylan at the Warfield 1980, Bloomfield riffing out turbo-charged monsters like it’s 1965 all over again.

Luke Torn

Q&A

With the Electric Flag’s Barry Goldberg

When did you first meet Michael?

Well, you know, it goes way back, 16 years old, in high school. He was from the suburbs, I was from the city, and we had high school bands. Mike and I had a band called King Dennis and the Kingsmen. We would play Sweet 16 parties. Those were a big deal, because we’d make sure we were the only guys there. It was pretty much a rock and roll band, it wasn’t really a blues thing then. We’d cover the Ventures, Johnny and the Hurricanes, all those kinda early instrumental bands.

When did Michael start checking out the blues scene?

The south Side of Chicago might as well have been Russia or something, nobody ever went down there. Except Michael started going down there . . . playing on Maxwell Street, as early as 14, 15 years old, just playing on the street corners and the sidewalks. He did it because of his love and his passion for the blues.

What do you most think attracted him most?

It was a cultural thing … mystical. It wasn’t like rock and roll. You know, it unleashed certain things in our heads, our minds, and our souls, that rock and roll didn’t. It cast a spell. The great guitar players that Michael could listen to, because in rock and roll at that time, there wasn’t a Hendrix or anyone like a virtuoso guy. With the blues, Michael was into B. B. King, Otis Rush, Muddy Waters, and he wanted to learn, he also discovered the country blues thing, too—Blind Lemon [Jefferson] and all those people.

He was playing both acoustic and electric in those days?

Oh, yeah, along with the folk music. He was an MC at this coffeehouse on Rush Street, which was sort of like the bourbon Street of Chicago, and he would conduct those shows, and bring down all those guys from the south side and west side, like Big Joe Williams, to play for these college kids and introduce them to this whole other life.

Like a switch was flipped?

Went we down to a place called Silvio’s, where Howlin’ Wolf was playing, and I followed Michael in there. You know, he was my leader. He had that kind of personality—you would follow him into hell. You know, I loved him man. Later on we were inseparable. He inspired me.

Did you see the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in their earliest days?

I was actually asked to play keyboards in the Butterfield Band in Chicago. I did a couple of gigs with Paul, and Michael and Paul invited me to come to Newport [in 1965]. We got in the car, we drove to Rhode Island, when we got there, their producer, Paul Rothchild, said ‘I don’t hear keyboards with the band,’ and so that brought me right down. The Butterfield Band was a huge success, though.

You were in the group for the Dylan set though…

Michael introduced me to Bob. And Bob asked me to play keyboards. I was playing organ. I had known the song, “Like a Rolling Stone,” because Michael had brought home the demo from when he had done the sessions. I learned the changes, so that was ok. And we did “Maggie’s Farm.” And it was a controversial reaction—some people liking it and some feeling that Bob had betrayed them.

Do you think Michael had a sense of the gravity of the moment?

I thought he had a great time. Just smiling. And we were just on a mission, blazing through in the name of rock and roll.

What was the reaction after the show that night?

Well, we just did our thing. And of course, Bob was upset—I guess. But I thought at that moment that a new movement had been born—a new focus and a new direction in music, and it changed that thing forever.

I understand Bloomfield was an ambassador for the blues in San Francisco, in the psych years?

Yeah, he did that to return the favor. Later on, with the Electric Flag and when he played with Butterfield, he had a relationship with Bill Graham and he got Bill to book all these other acts. He said “Hey, they have agents, too.” You know, bring in Muddy, bring in Wolf, bring in B.B. King. Bill started doing that, and Michael was pretty much responsible for that.

What was the blueprint of the Electric Flag?

He was uncomfortable with the Butterfield Band, so he approached me to start the Electric Flag—he wanted to have an all-American music band, that could play every style of American music—from blues to Motown—and he liked that until it became on the verge of becoming a supergroup.

What kind of a turning point was Monterey Pop?

We premiered our first album, Long Time Comin’ there, and that was intense because all eyes were on us. Michael was freaked out by all of that. There was so much pressure on him because he was the leader of the band. His personality, his very intense personality, caught on fire, and consequently he couldn’t sleep. He couldn’t turn it off. And that was a part you could hear in his music, that made his music so special. No one ever had that intensity, that burning, in their playing. Unfortunately, it was a curse at the same time

That led to the Electric Flag’s demise?

To me, from the reaction of the crowd, we accomplished our goal, our mission. We had an above-average set, I think. After that, we had sorta like won the battle, won the war. We were on a course. And unfortunately, in those days, there were a lot of drugs around. Our manager tried to talk to us, ‘You know, hey man, if you guys just play it cool, you could retire at the age of 40.’ But we were on a different course, unfortunately, and let that get the best of us, and the band started to deteriorate. It became awful personality-wise.

As Michael receded from the spotlight, do you think he was a misunderstood figure?

He didn’t like the spotlight, he didn’t like the pressure. He had bad insomnia and he liked the comfort zone of his room. He didn’t really need the fame and glory, he shunned away from that. He was a private kind of guy.

INTERVIEW: LUKE TORN