The filmmaker Derek Jarman, a veritable English visionary, wrote his book Modern Nature about his experience living alone in a cottage in Dungeness, on the English south coast. Jarman decamped to this terminal beach knowing he was dying, but in the process created a late body of work – films, writings and artworks – in which he exploited his closeness to the Earth, and the focus gained when living in a remote place, away from metropolitan London.

The filmmaker Derek Jarman, a veritable English visionary, wrote his book Modern Nature about his experience living alone in a cottage in Dungeness, on the English south coast. Jarman decamped to this terminal beach knowing he was dying, but in the process created a late body of work – films, writings and artworks – in which he exploited his closeness to the Earth, and the focus gained when living in a remote place, away from metropolitan London.

ORDER NOW: Bob Dylan and The Review Of 2023 star in the latest UNCUT

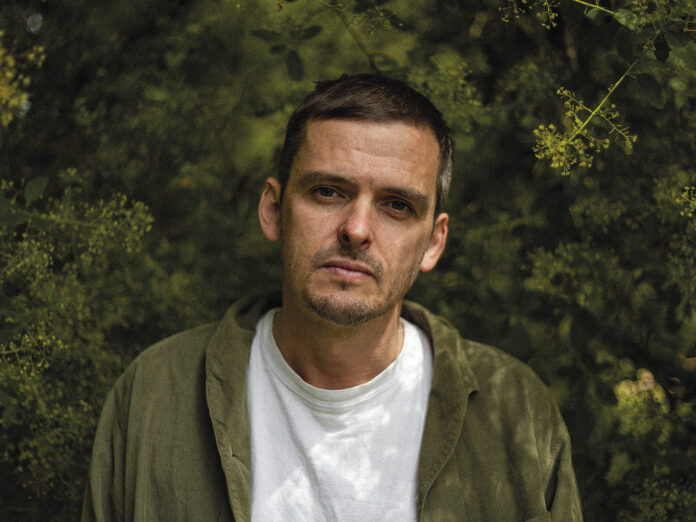

He was not the first English artist to seek renewal and resuscitation in a rural setting. Jack Cooper of Modern Nature, the band named after Jarman’s book, has also recently moved from London to a village in East Anglia. Not far from what’s known as ‘Constable country’, he chose to settle in a timeless patch of Deep England, in a settlement formed from a classic, jarring English knot of knurled, half-timbered houses ringed by geometric housing estates.

No Fixed Point In Space is the group’s fourth album since 2019, if you include mini-album Annual. Frequently stated, and with good reason, is their similarity with the strange, sprawling music of late Talk Talk – not only in their songs’ fluid structures, open acoustic and sense of wonder. On previous releases they have also occasionally paid convincing homage to Can/Neu!-like repetitive rhythms.

But they also come across more advanced than their years, partly thanks to Cooper’s ability to engage a wide spectrum of musicians from outside the band to accentuate and enhance the audio palette. Previous releases have seen the addition of British improvisors to the core line-up, such as John Edwards and Evan Parker. On the new album, string players Anton Lukoszevieze, Mira Benjamin and Heather Roche from Apartment House are added to Cooper’s regular collaborators Jeff Tobias and Jim Wallis, as well as improvisers Dominic Lash and Alex Ward, pianist Chris Abrahams of The Necks, and – truly a kicker – a guest appearance by vocalist Julie Tippetts (formerly Driscoll) on two tracks.

Cooper occupies an interesting place between experimental rock and songwriting and more hardcore contemporary music and jazz. Like Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood he is making the idea of being a ‘songwriter and composer’ cool again. On No Fixed Point…, Modern Nature have moved further away from conventional rock structures. Good things take time; none of this thoughtfully conceived music is rushed. It has precedents in some of David Sylvian’s work, the last solo album by Talk Talk’s Mark Hollis, the more ambient side of Bark Psychosis and 2013’s Field Of Reeds by These New Puritans, thanks to its slow, ruminative pacing and the recurrent use of classical instruments (strings, woodwinds, saxes) with a stripped-back guitar/bass/drums combination. In his final years Hollis explored his affinity with small-scale chamber and minimalist music and experimented with scoring. Cooper has also referred to his own use of scores to arrange the music here. It’s one of those albums that sounds all of a piece – more of a suite than a collection of diverse songs. At the same time the spontaneity of Cooper’s adeptly chosen line-up breaks the music open like a poppy head, its seeds scattering out and away into the world.

Thematically their songs skim across micro-observations of nature – the murmuration or flocking motions of starlings, the flow of a river. Everything about the album evokes organic states of being and the revolutions of sun and moon that determine Earth’s metabolic cycles. The landscape evoked is unmistakably English rather than nature red in tooth and claw. The songs feel like meditations in the blue hour, in the time of dew, the rural morning that feels like a perpetual Sunday. The opening “Tonic” edges into consciousness, as if the music is taking its first breaths. “Orange” orbits around a droning chant, enraptured at the sun’s infinite circles on a “fragile, brackish morning”.

Light, flora and the heavenly bodies are lit up in “Sun”, with Cooper going into raptures about “impossible webs in the wind”. “Cascade” broods and tumbles amid withered boughs and brambles and a beautiful combination of scudding chamber arrangements and itchy guitar. It overflows into a bluesy, catcalling refrain in which Cooper’s voice is doubled with Julie Tippetts.

For much of the time, bassist Lash and drummer Wallis patter and pulsate in flurries and eddies across Cooper’s lyrics, not so much accompanying him as scurrying ant-like under his visionary’s footsteps. Micro-rhythms shimmy up to nibble at something on the surface then shrink back to the depths. Shivers ripple through a song’s form like a flock of birds about to migrate. It fulfils Cooper’s ambitions to make a music impregnated with “the swing of humans”, answering to the hydraulics of the human body, not the digital matrix of the sequencer and the hard disk. For this reason, too, Modern Nature insist on recording in the last functional analogue studio in London, and to record as spontaneously and ‘live’ as possible. It definitely benefits this record, which has the character of those magnificent late Talk Talk records – reputedly captured with a single ambient mic like early jazz takes – or the sense of musicians gathered in a three-dimensional space that John Wood and Joe Boyd achieved in their legendary folk-rock recordings for Island at Sound Techniques in the late ’60s and early ’70s. In fact, the whole endeavour harks back in spirit to that time of opportunity in English music in the early ’70s, when jobbing musicians such as Danny Thompson, John Stevens or Keith Tippett could add their magic to any number of folk-rock, jazz or pop records.

There are only seven tracks, nothing longer than seven minutes, a sense of everything that needed saying having been said. The final “Enso” – Japanese for ‘circle’ – ends almost prematurely, not outstaying its welcome. Cooper sings, “It’s impossible to take in/It’s impossible to see” – a hint at the biggest thought experiment our anthropocenic species is dealing with right now, the fact of humanity’s existence as a part of nature rather than separate from it; we are so much a part of it that we can’t see it.

This incarnation of Modern Nature has delivered a slim but rich volume of musical poetry, that demands a certain commitment to appreciate its quiet fervour. If there’s one criticism to level at No Fixed Point In Space, it’s that the album never quite catches fire. But perhaps an uncontrolled blaze is not the – fixed – point. In smoldering for so long, it says a good deal about the current state of the nation, where the visionary spirit has been bogged down and infested with sewage. A passion burns slow and low in Modern Nature, a deep rural sound kindled in the undergrowth, struggling to put down its roots and flourish. There is a keenness for renewal in Modern Nature’s cyclical sound, one that reassures you that the sunken land may yet begin to rise again.