Fourteen years into the sainthood of Kurt Cobain, it’s hard to watch Nirvana on MTV’s Unplugged without the benefit of grim hindsight. The set, with candles and stargazer lilies, looks dressed for a wake at a well-appointed funeral home. As early as the second song – a naked version of “Come As You Are” – Cobain is singing “No, I don’t have a gun”. On the next track – a weary busk through The Vaselines’ warped Sunday School spiritual, “Jesus Don’t Want Me For A Sunbeam” – the singer can be heard moaning: “Don’t expect me to die for thee”. Death and dread are everywhere. Sure enough, Cobain was gone within five months. But then, morbidity was hardly a novelty for Cobain. At their best, before Cobain’s attempts to anaesthetise himself took their toll, Nirvana were an act of catharsis. If Cobain didn’t exactly cultivate his hurt, he knew how to make use of it. You can see the peculiarity of his position in a throwaway remark at the Unplugged show. Before introducing “Where Did You Sleep Last Night?”, he relates the story of how a guy has been trying to hawk Leadbelly’s guitar for $500,000. “I even asked David Geffen personally if he would buy it for me, but he wouldn’t do it.” It is, by any standards, a peculiar jam for a punk to find himself in. At the time, the funereal pace of Unplugged, and its sense of restraint, seemed at odds with Nirvana’s recorded output. But Kurt’s death, and the appropriation by lesser talents of the grunge formula, throw new light on it. Cobain may be mourning his own misery, but he’s also paying homage to his influences, and moving on musically. To the nervous MTV executives who now hail it as a classic, Nirvana’s performance was perverse. There was no “…Teen Spirit”, and precious little from Nevermind. The mistakes were not corrected. But the perversity was precisely targeted: offered a commercial platform, Cobain decided to spread the love, providing The Vaselines with a pension plan, giving David Bowie an appreciative nod (“The Man Who Sold The World”: another joke about selling out), and sharing the stage for three songs with his old heroes The Meat Puppets. If it was ever obvious, the magic of The Meat Puppets and The Vaselines is now a secret known only to a few, but the frayed cover of “Where Did You Sleep Last Night?” is among the most powerful performances of Nirvana’s career. Patti Smith recently noted that she could hear echoes of Roscoe Holcombe in Cobain’s voice, and not just because of Holcombe’s version of this song (in its country guise as “In The Pines”). And it’s true. A television studio isn’t exactly a country porch, but the intimacy of the performance reveals Cobain’s folk roots, before burying them in torment. He also twists the song in his own image. When he moans about shivering the whole night through, this murderous folk tune becomes a heroin lament. There is, if we’re honest, a little too much lethargy on display here, but as a rule, the sparseness of the performances works in Cobain’s favour. Krist Novoselic may joke in the Making Of... doc that the group were trying “to show off our softer side, like scented toilet paper”, but the pared-down arrangements, with Pat Smear and Lori Goldston filling in on guitar and cello, offer thrilling hints of how Nirvana might have developed. Less spit, but more blood. “All Apologies” and “Dumb” are beautifully understated, and Cobain’s solo rendering of “Pennyroyal Tea” is chilling, even if the line “I have very bad posture”, remains a peculiar opening gambit. Suicidal impulses and addiction are rock’n’roll; lumbago isn’t. Comparing the rehearsals with the broadcast shows, it’s plain that Cobain was nervous in front of the crowd. Watching their almost religious anticipation, you can sense why. Add in overblown testimonies from the MTV crew, who treat the show as if it was the first ringing of the Liberty Bell, and you can see that even at a moment of artistic triumph, Kurt Cobain had reasons for feeling like a man out of time. EXTRAS: Original edited broadcast, Making Of, 22 minutes of rehearsals. ALASTAIR McKAY

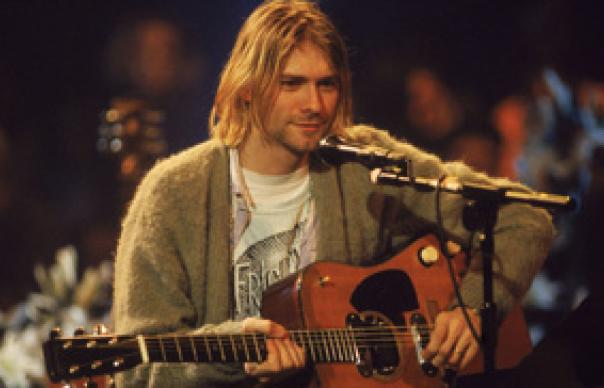

Fourteen years into the sainthood of Kurt Cobain, it’s hard to watch Nirvana on MTV’s Unplugged without the benefit of grim hindsight. The set, with candles and stargazer lilies, looks dressed for a wake at a well-appointed funeral home. As early as the second song – a naked version of “Come As You Are” – Cobain is singing “No, I don’t have a gun”. On the next track – a weary busk through The Vaselines’ warped Sunday School spiritual, “Jesus Don’t Want Me For A Sunbeam” – the singer can be heard moaning: “Don’t expect me to die for thee”. Death and dread are everywhere. Sure enough, Cobain was gone within five months.

But then, morbidity was hardly a novelty for Cobain. At their best, before Cobain’s attempts to anaesthetise himself took their toll, Nirvana were an act of catharsis. If Cobain didn’t exactly cultivate his hurt, he knew how to make use of it. You can see the peculiarity of his position in a throwaway remark at the Unplugged show. Before introducing “Where Did You Sleep Last Night?”, he relates the story of how a guy has been trying to hawk Leadbelly’s guitar for $500,000. “I even asked David Geffen personally if he would buy it for me, but he wouldn’t do it.” It is, by any standards, a peculiar jam for a punk to find himself in.

At the time, the funereal pace of Unplugged, and its sense of restraint, seemed at odds with Nirvana’s recorded output. But Kurt’s death, and the appropriation by lesser talents of the grunge formula, throw new light on it. Cobain may be mourning his own misery, but he’s also paying homage to his influences, and moving on musically.

To the nervous MTV executives who now hail it as a classic, Nirvana’s performance was perverse. There was no “…Teen Spirit”, and precious little from Nevermind. The mistakes were not corrected. But the perversity was precisely targeted: offered a commercial platform, Cobain decided to spread the love, providing The Vaselines with a pension plan, giving David Bowie an appreciative nod (“The Man Who Sold The World”: another joke about selling out), and sharing the stage for three songs with his old heroes The Meat Puppets.

If it was ever obvious, the magic of The Meat Puppets and The Vaselines is now a secret known only to a few, but the frayed cover of “Where Did You Sleep Last Night?” is among the most powerful performances of Nirvana’s career. Patti Smith recently noted that she could hear echoes of Roscoe Holcombe in Cobain’s voice, and not just because of Holcombe’s version of this song (in its country guise as “In The Pines”). And it’s true. A television studio isn’t exactly a country porch, but the intimacy of the performance reveals Cobain’s folk roots, before burying them in torment. He also twists the song in his own image. When he moans about shivering the whole night through, this murderous folk tune becomes a heroin lament.

There is, if we’re honest, a little too much lethargy on display here, but as a rule, the sparseness of the performances works in Cobain’s favour. Krist Novoselic may joke in the Making Of… doc that the group were trying “to show off our softer side, like scented toilet paper”, but the pared-down arrangements, with Pat Smear and Lori Goldston filling in on guitar and cello, offer thrilling hints of how Nirvana might have developed. Less spit, but more blood. “All Apologies” and “Dumb” are beautifully understated, and Cobain’s solo rendering of “Pennyroyal Tea” is chilling, even if the line “I have very bad posture”, remains a peculiar opening gambit. Suicidal impulses and addiction are rock’n’roll; lumbago isn’t.

Comparing the rehearsals with the broadcast shows, it’s plain that Cobain was nervous in front of the crowd. Watching their almost religious anticipation, you can sense why. Add in overblown testimonies from the MTV crew, who treat the show as if it was the first ringing of the Liberty Bell, and you can see that even at a moment of artistic triumph, Kurt Cobain had reasons for feeling like a man out of time.

EXTRAS: Original edited broadcast, Making Of, 22 minutes of rehearsals.

ALASTAIR McKAY