There’s an alternate universe in which Otis Redding’s private jet lands safely on December 10 1967, where Otis returns to the Stax studio in Memphis, completes his single “(Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay”, and puts it at the centre of a radical album that transforms soul music as we know it. Redding goes on to thrive, the star of the Monterey Festival becoming the thread that links 60s Stax, 70s Motown, flower power and the sonic advances of Hendrix, Sly Stone and Stevie Wonder.

In the real world, of course, Redding’s Beechcraft H18 crashed into Lake Monona, killing him and his touring band, with only trumpeter Ben Cauley surviving. A week later, Redding’s funeral in his hometown of Macon, Georgia attracts around 5,000 mourners, and his last ever recording ends up topping the charts the world over. His record label Stax/Volt and its parent company Atlantic, understandably keen to satisfy a desire for a long-player, rush-release an accompanying album called Dock Of The Bay, a curious mish mash of recent singles, b-sides and the odd cover.

It served as a rather unsatisfactory long-playing eulogy, especially as it emerged that Stax were sitting on a mountain of unreleased Otis sessions recorded throughout 1967. The first batch were released in June ’68 as The Immortal Otis Redding – a dozen unreleased tracks, four of which became hit singles, including the deathless, horn-led funk of “Hard To Handle”. It was followed, a year later by

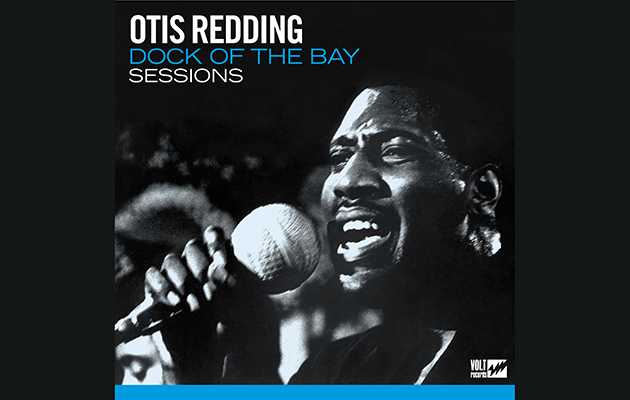

The Dock Of The Bay Sessions comprises 12 of the best recordings from this astonishingly fertile last few months of Redding’s life. It also indulges that counterfactual in which Redding survives: Bob Stanley’s sleevenotes for this album – a parody of the kind of breathless prose you used to get on the back of 1960s LPs – are written as if this was January ’68 and Redding is still alive, looking forward to his biggest ever hit. “This album is the first indication of a new Otis Redding,” writes Stanley, “one that has slayed audiences in Europe, one which won him a whole new crowd at the Monterey International Pop Festival.” Stanley digs up some wonderful little nuggets of info – for instance, that Lionel Bart was among the adoring figures who saw Otis at those legendary Stax/Volt roadshows in London in April 1967; and that Otis was frustrated by playing 20-minute sets as part of a showcase. “I won’t ever come to this country again with the same kind of package,” he apparently told the New Musical Express. “I want to give the people at least 45 minutes, so I can be the star of the show, and I can do all the numbers they want to hear.”

Just as he wanted to transcend his showcase billing, Redding presumably wanted to present his albums differently. More than any other R&B artist of this era, Otis Redding was trying to break out of the restrictions of being a “singles artist” and embrace the concept of the long-player. From 1965’s Otis Blue, his albums were programmed like the bill of a variety show: you’d get a few original songs, some recent soul standards by the likes of Sam Cooke, Ben E King or Smokey Robinson, and the odd contemporary pop cover by the likes of the Beatles and the Stones.

Get Uncut delivered to your door – click here to find out more!

The choices on Dock Of The Bay Sessions suggest an artist who was refining his songwriting, someone concentrating more on character development. He was, from all accounts, a huge fan of Bob Dylan’s ability to create elliptical imagery through lyrics (something apparent on the title track, which almost serves as a Hamlet-like soliloquy); he was also, according to his widow Zelma, obsessed with Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (“he’d play that Beatles album every time he was at home!”). There is only one cover version here – the closer is an emotive reading of Jester Hairston’s gospel standard “Amen”, best known as a hit single for Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions. Otherwise, every track here is an original track, written by Otis, usually with help from his Stax colleagues.

It’s not clear who has decided on this particular running order. Redding’s wingman Steve Cropper – guitarist, keyboard player and main co-writer for those final years – doesn’t appear to be involved in the project, but it’s a decent alternate history and one that hangs together well. The title song is joined by six tracks from Immortal, three from Love Man and two from the 1992 compilation Remember Me.

All of these originals see him going through the emotional mill. On the furious, uptempo “Love Man” he’s strutting like a boxing champion, advertising his height and weight to the world (“Six feet one, weight two-hundred-ten…”), reminding himself with each rhythmically repeated syllable (“cau-cau-cau-cau-cau-cause I’m a LOVE MAN”). The sexual braggadocio continues with more intensity on “Pounds And Hundreds” (“I got some loving by the pound/and by the hundreds, honey”).

But it’s not long before he’s being put through the ringer. On “The Happy Song (Dum-Dum-De-De-De-Dum-Dum)“ the comforting cocoon of domesticity (“she holds me and squeeze me tight/she tells me ‘big O, everything’s all right’,”) has reduced him to pre-literate babyhood. On “Champagne And Wine” he’s advertising his emasculation (“I’m a man now, full grown man/you got me eating from the tip of your hand”). On the stately gospel blues “Think About It” he’s pleading to a woman who has wronged him; on the ultra-slow “Gone Again” he’s having an existential crisis (“picture a winter/without any snow… picture a river with nowhere to flow”). “I’m A Changed Man” is one of the most instructive documents in the secularisation of religious gospel music – here the desire for love has transformed him spiritually (“I’m a changed man/I’ve been baptised”). Just transform the word “baby” for “Jesus” and the song could be a hymn.

All the tropes of Redding’s vocal arsenal are on display. “Hard To Handle” doesn’t really have a written melody – the entire tune is Otis riffing around the horn arrangement, effortlessly locating the blue notes as effectively as any jazz soloist. On the gently funky ballad “Think About It” – based around Steve Cropper’s clipped, ska guitar chords, Booker T Jones’s churchy piano and funereal horns – he’s pleading with the lover who has rejected him, reaching a crying crescendo (“just wait before you tell me goodbye”) has him howling at the top of his register in those thrilling, chordal multiphonic tones.

Best of all might be the brokenhearted, coma-paced 6/8 ballad “I’ve Got Dreams To Remember”, where the melodic phrasing sounds like a series of choked sobs (“I know you’ll say he was just a *frey-end*/but I saw you kiss him *agin and *agin”). Redding’s racked, hurt voice seems freighted with decades of hurt, like the sound of an elderly man, recounting the broken love affair that finished him off. Astonishingly, he was only 26 when he recorded it.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner