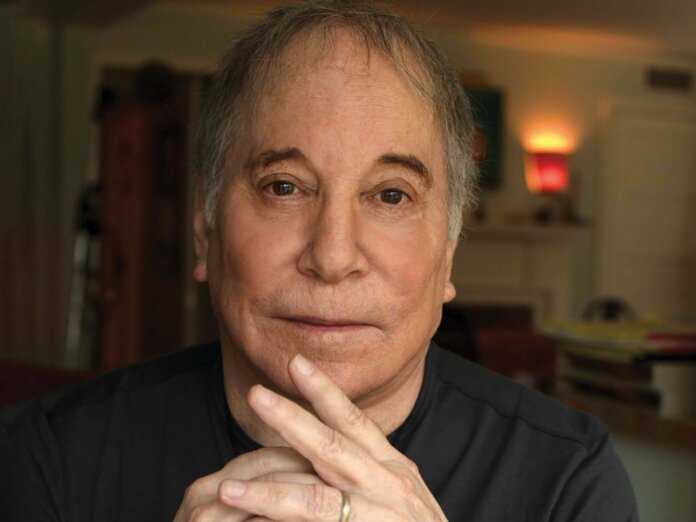

Paul Simon is an artist filled with glorious paradoxes. He’s the secular Jew who has made some of the greatest pieces of Christian pop music; the non-believer whose lyrics are obsessed with faith; the all-American boy who has immersed himself in the music of Jamaica, South Africa, Brazil and Olde ...

Paul Simon is an artist filled with glorious paradoxes. He’s the secular Jew who has made some of the greatest pieces of Christian pop music; the non-believer whose lyrics are obsessed with faith; the all-American boy who has immersed himself in the music of Jamaica, South Africa, Brazil and Olde England; the folk singer who makes soul music with the world’s top jazz musicians; the choir-boy tenor who was rapping, conversationally, long before hip-hop. He’s perhaps the most complex and interesting figure on that shortlist of America’s greatest living songwriters – alongside Bob, Stevie, Carole, Brian, Bruce, Smokey, Dolly and the rest. You wouldn’t see Dylan deciding to write a piece of Schoenberg-inspired 12-tone serialism as an academic exercise – using every note in a chromatic scale – and ending up with a limpid, soulful waltz like “Still Crazy After All These Years”. It’s unlikely that Dolly Parton would have jammed with township musicians from Soweto and been inspired to sing about Elvis Presley’s home in Memphis; a sixtysomething Brian Wilson wouldn’t have written a salsa musical about a Puerto Rican murderer, a seventy-something Springsteen is unlikely to make an album on Harry Partch’s microtonal instruments.

Simon’s latest album continues that exploratory spirit. Seven Psalms is a cycle of seven songs presented as a single 33-minute track. The idea apparently came to him in a dream and, after a year of frequently waking in the dead of the night to scribble down lyrical ideas, it was completed exactly a year later, on the 25th anniversary of his father’s death.

Simon is now 81, and Seven Psalms can certainly be seen as the summation of a career that has lasted more than 66 years. It draws together several recurring themes in his lyrics: religious imagery, secular hymns, reflections on death, lyrics that read like quizzical short stories. The album starts with “The Lord”, a baroque-inflected two-chord piece that is repeated, with increasing urgency, several times throughout the album. It is a hymn that starts by attributing all beauty in the world to a cosmic creator. “The Lord is a virgin forest, the Lord is a forest ranger”, he sings. “A meal for the poorest, a welcome door to the stranger”. Then suddenly, the mood shifts, the florid guitar becomes more strident and, instead of crediting this force of nature with miracle and wonder, Simon shifts from New Testament to Old and blames God for the world’s evils – from disease to war to global warming. “The Covid virus is the Lord/The Lord is the ocean rising/The Lord is a terrible swift sword”.

The song references various moments in Simon’s career. The medieval-sounding guitar riff is reminiscent of the “Anji” flourish that Davy Graham taught him 60 years ago; the liturgical air recalls both the first Simon & Garfunkel album and the more recent sardonic spiritual quest of So Beautiful Or So What. When Simon sings, “The Lord is a face in the atmosphere/The path I slip and I slide on”, it’s clearly a nod to “Slip Slidin’ Away” and that song’s cheerful meditation on the inevitability of death.

The mood lightens a little on the airy “Love Is Like A Braid”, a major-key song where the lyrics of heaven and judgment are intoned arrhythmically, like an epic poem. By the time we reach the jokey, ragtime-inflected “My Professional Opinion”, we can hear Simon almost beating himself up for the fruitless soul-searching of the previous songs. “I’m gonna carry my grievances down to the shore, wash them away in the tumbling tide”, he coos. As another nod to the past, we can hear him playing the same percussive bass harmonica sound that we all remember from “The Boxer”.

“Your Forgiveness” is the most ambitious song here; an episodic, flamenco-tinged piece, with baroque flutes that resemble the Andean pipes on “El Condor Pasa” and a harmonium drone from 1972’s “Papa Hobo”. As he ponders sin and forgiveness, the arrangement gets more complex – there is a baroque string quintet, featuring the theorbo, chalumeau and viol de gamba, as well as a subtly deployed arsenal of rhythmic instruments – temple bowls, gongs, frame drums, South Indian ektars and bass harmonicas.

“Trail Of Volcanoes” is the most rhythmic track on the album, a single-chord drone based around some subtle West African percussion and a simple descending guitar riff, with lyrics that seem to be about immigration and asylum (“those old roads are a trail of volcanoes/Exploding with refugees”). It’s also the first appearance of Simon’s wife Edie Brickell, whose sparkling lead lines and playful harmonies are a welcome shard of light among the melancholy. She returns on the final track, “Wait”, where Simon’s narrator seems to be chaotically preparing for death (“Wait, I’m not ready/I’m packing my gear”). Yet there’s a sense of resigned joy, as Simon moves into the pulsating 6/8 time signature he loves so much. “I need you here by my side/My beautiful mystery guide”, he sighs, before Brickell joins him on the final verse. “Heaven is beautiful”, she sings. “It’s almost like home”. It would be a magnificent way to end a magnificent career, but Simon probably has yet more ideas in him.