The classic ’86 solo album, lavishly packaged with extras…

A pop star isn’t supposed to have his biggest hit at the age of 36, 16 years after his debut and six albums into his solo career. And, as we’re constantly told, prog rock dinosaurs were supposed to have been slain in the evenements of 1977. Peter Gabriel, of course, seemed magnificently unconcerned by such details. So is the sound of a man who has slowly absorbed each new wave – post-punk, New Pop, synth pop, Afrobeat – and syncretised them into an album that would transform this cult experimentalist into one of the big beasts of global pop.

Has it dated? So much 80s music – or, to be specific, pop recorded between those wilderness years of 1983 and 1988 – is rendered almost unlistenable today, due to those hallmarks of high 80s production: gated reverb on the snare, glutinous DX7 pianos, Simmons electric tom-toms, heavily chorused guitars, and so on. From the thunderous Linn drums and fretless bass that open “Red Rain” much on So can certainly be carbon-dated by these tropes, although it’s not always a problem.

Sometimes the state-of-the-art production is part of the appeal. The digi-funk bombast of “Big Time” is a defining totem of high-end 80s production, pitched somewhere between Scritti Politti’s “Wood Beez” and Trevor Horn’s “Owner Of A Lonely Heart”. And the funk shuffle of “Sledgehammer” now sounds almost timeless, thanks to it being a much-sampled hip hop fixture. Elsewhere the production interferes, like the bell-like Fairlight sounds that mar “That Voice Again”, or the whistling ambient accompaniment on “Mercy Street” (the orchestral recreation of the latter track on last year’s New Blood is possibly preferable). Laurie Anderson’s co-write “This Is The Picture (Excellent Birds)” is a series of jerky abstractions in search of a song and never really fitted on here; conversely, it’s the oft-overlooked “We Do What We’re Told (Miligram’s 37)” that’s one of the best tracks: an Eno-esque miniature that ends just as it starts getting interesting.

This is a lavish package, with extras including a two-hour Live In Athens DVD and a second DVD featuring the excellent hour-long “Classic Albums” documentary on the making of So. But the most interesting disc is the “DNA CD”, tracing the “audio evolution of So”. Each track glues together several different versions of each song, taken from various stages in their development. We start with the rawest demo – usually just Gabriel accompanying himself on a digital piano – and then, with every verse, gradually revert to subsequent, more polished demos of the song until, by the end of the track, we are left with a rough template for the finished version.

They are unique glimpses into the recording process, a format that you can expect to be copied on other reissue packages. “Red Rain” and “Sledgehammer” both start with just a spartan, clunky piano riffs, with Gabriel singing gibberish, wordless lyrics. “Big Time” starts as a jangly gospel piano instrumental, then mutates into a guitar-led funk jam, slowly adding garbled synth horns. You can hear a ghostly tenor saxophone wailing in the background of “Mercy Street”, and you can hear how Tony Levin’s syncopated, kora-like fretless bass line, which now sounds so central to “Don’t Give Up”, turns out to have been a last-minute addition to a song which started out as a country Baptist hymn (with Dolly Parton initially earmarked for Kate Bush’s role).

The package also includes a 12” single featuring three tracks. There’s an intriguing piano-led gospel version of “Don’t Give Up”, and two previously unheard tracks: “Courage” is a weirdly appealing Talking Heads pastiche that wouldn’t sound out of place on Remain In Light (“I’ve been beating my head against a rubber wall”), while “Sagrada Familia” is another promising unused demo, mixing African high-life guitar, Tony Levin’s rubbery bass and some frenetic Latin percussion with an intriguing lyric about Antonio Gaudi and Sarah Winchester. Both sound utterly untouched by any of the high-80s tropes mentioned earlier – it would be fascinating to hear an entire album like this.

John Lewis

Q&A

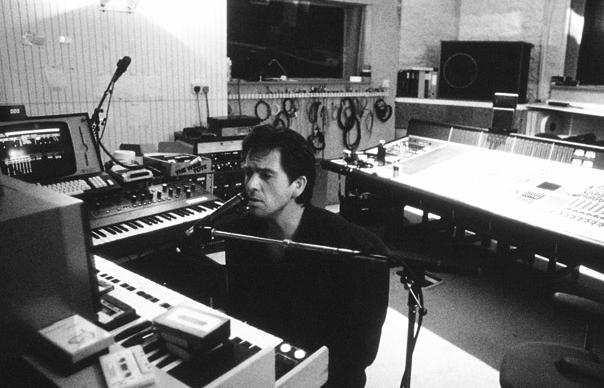

DANIEL LANOIS

Was So a conscious attempt to make a “pop” record?

Not in a cynical way, but Peter definitely wanted to make proper songs. I said to Peter, early in the session, “I know you hate hi hats and cymbals, but you’ve made five fucken’ albums without them, so just get over it! Some of us actually like records that groove, ferchrissakes!” And I think that liberated Peter to explore a funkier, more soulful, more playful, more emotional side to his character.

Was it a laborious process?

I was living in Peter’s house for a year, in what I call the Bell Tower. We spent nearly six month on preps: not only setting up sounds but also providing Peter with rock solid advice about which way to go and what we might need. And we wrote the songs as a tight trio – just me, guitarist David Rhodes and Peter with his beatbox. We only proceeded with ideas if there was a spark of magic in that format. The bass and drums came much, much later, which is the opposite of how you’d usually work.

It sounds like there were dozens of versions of each song recorded…

When you work with Peter, there are lots of ideas flying around all the time. You have to become a master librarian just to keep track of the best stuff. He actually did have a library – not a hard-drive, but a physical librarly, a big closet filled with two-inch tapes! – and you’d store stuff there. I was an obsessive notekeeper in those days, so I logged every take and every synth sound, which mean that I was able to get back to any sound that Peter liked. So every one of these songs you can find at least

a dozen versions.

INTERVIEW: JOHN LEWIS