After the legal case, the musical one. Strong second from the Waters-less Floyd, expanded into a 6 disc box set.... Roger Waters believed that without him, there could be no Pink Floyd. Floyd without Waters? It was, he said, like the Beatles without John Lennon – he regarded the line-up led by David Gilmour, which also included founder members Nick Mason and Rick Wright, as having no right to the brand name – a point he pursued in court, calling them “a spent force”. Waters had, after all, been the driving force behind Dark Side Of The Moon, Wish You Were Here, The Wall and The Final Cut. When the first Gilmour-led Floyd album, 1987’s A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, proved both flabby and insubstantial, it appeared that he might have been right. With 1994’s The Division Bell, however – repackaged here as either a vinyl remaster or a box set showcasing four different audio formats - Gilmour’s Floyd didn’t only recapture something of the group’s classic sound. He also found what Waters had historically supplied to the group: something to say. It’s probably no wonder that as late as the group’s 2005 Live8 reunion, Waters was still fuming about the fact that there remained a disturbingly large number of people unable to discern the difference between Dark Side and The Division Bell, made under the same band name, but products of two different sides of Floyd’s Yin and Yang. All great Floyd albums need a concept and with his second wife (novelist Polly Samson) as his lyrical foil, for The Division Bell Gilmour came up with the theme of communication and the space between us. It was most overtly expressed in the song titles: “Lost For Words”, “Keep Talking” and “Poles Apart.” The concept might have been nebulous, but it was sufficient to give the album the consistency and coherence that A Momentary Lapse Of Reason had lacked. What’s more, Gilmour went to great lengths to ensure that The Division Bell was genuinely a group album. Mason, who on its predecessor had shared drum duties with machines and Carmine Appice, was back firmly in the driving seat. Perhaps even more significantly, Rick Wright – sacked by Waters during The Wall and reduced to a salaried session man on subsequent Floyd projects – was fully rreinstated. His photo hadn’t even been included on A Momentary Lapse Of Reason but on The Division Bell, he’s credited as co-writer on five tracks, and on the standout “Wearing The Inside Out” takes his first lead vocal since Dark Side Of The Moon. The empathy between his keyboards and Gilmour’s guitar – heard to best effect on the instrumentals “Cluster One” and “Marooned” – is at the album’s musical heart. It all feels very reassuring. Bob Ezrin, who had produced The Wall, was back at the helm and Dick Parry, whose sax playing had graced Dark Side Of The Moon and Wish You Were, returned for the first time in almost 20 years for "Wearing the Inside Out". All of these elements meant The Division Bell sounded more like a classic Floyd record than 1983’s The Final Cut, Waters’ swansong with the band. Certainly, Gilmour’s U2 imitation on “Take It Back” was a mistake and the sampling of Stephen Hawking’s voice on “Keep Talking” doesn’t convince. But they’re rare blemishes: the likes of “What Do You Want From Me” with its “Comfortably Numb”-style guitar solo, the ethereal “Poles Apart” with its inventive Michael Kamen orchestration and the magisterially doomy ballad “High Hopes” proved not only that there could be life after Waters but also ensured that Pink Floyd’s – apparently final – studio album saw them go out on a high. Lyrically it’s tempting to read the album’s themes of ruptured communication as a broadside against Waters, and “Lost for Words", as Gilmour’s “How Do You Sleep”, when he sings: "So I open my door to my enemies/And I ask could we wipe the slate clean/But they tell me to please go fuck myself/You know you just can't win". The references to “the day the wall came down” on “A Great Day For Freedom” may have been about the reunification of Germany but might also be interpreted as another sideswipe at Waters. And who can Gilmour be addressing but Waters in “Poles Apart” in acid lines such as “Hey you, did you ever realise what you'd become?” Gilmour has diplomatically denied that any of The Division Bell is aimed at his former colleague. Waters can be forgiven if he remains unconvinced by such protestations. On its release The Division Bell went to number one on both sides of the Atlantic, Floyd’s first chart-topper in America in 15 years. Yet it was poorly received by critics and dismissed as an anachronism. Pink Floyd seemed at best an irrelevance and at worst a bunch of middle-aged millionaires engaged in a bitching match over the division of the spoils. Gallagher versus Albarn offered a far more titillating street fight than the High Court battles of Gilmour versus Waters. Twenty years on, the passage of time now allows for a rather different judgment. EXTRAS: 7/10 The six-disc box set contains no actual new music, focusing instead on an audiophile smorgasbord: an audio CD of the 2011 remaster; a remastered double vinyl copy of the original album; and a Blu-ray disc with previously unreleased 5.1 mix, HD audio mix and video for “Marooned” directed by Aubrey Powell. There is also a one-sided blue vinyl 12” containing “High Hopes”/“Keep Talking”/“One Of These Days (Live)”, a red vinyl 7” single (“Take It Back”/“Astronomy Domine (Live)” and a clear vinyl 7”single (“High Hopes/ “Keep Talking”), plus a 24-page booklet and five art prints designed by Hipgnosis/StormStudios. There is also a new vinyl remaster, but no new CD: the 2011 remastered single CD remains in catalogue. Nigel Williamson

After the legal case, the musical one. Strong second from the Waters-less Floyd, expanded into a 6 disc box set….

Roger Waters believed that without him, there could be no Pink Floyd. Floyd without Waters? It was, he said, like the Beatles without John Lennon – he regarded the line-up led by David Gilmour, which also included founder members Nick Mason and Rick Wright, as having no right to the brand name – a point he pursued in court, calling them “a spent force”. Waters had, after all, been the driving force behind Dark Side Of The Moon, Wish You Were Here, The Wall and The Final Cut. When the first Gilmour-led Floyd album, 1987’s A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, proved both flabby and insubstantial, it appeared that he might have been right.

With 1994’s The Division Bell, however – repackaged here as either a vinyl remaster or a box set showcasing four different audio formats – Gilmour’s Floyd didn’t only recapture something of the group’s classic sound. He also found what Waters had historically supplied to the group: something to say. It’s probably no wonder that as late as the group’s 2005 Live8 reunion, Waters was still fuming about the fact that there remained a disturbingly large number of people unable to discern the difference between Dark Side and The Division Bell, made under the same band name, but products of two different sides of Floyd’s Yin and Yang.

All great Floyd albums need a concept and with his second wife (novelist Polly Samson) as his lyrical foil, for The Division Bell Gilmour came up with the theme of communication and the space between us. It was most overtly expressed in the song titles: “Lost For Words”, “Keep Talking” and “Poles Apart.” The concept might have been nebulous, but it was sufficient to give the album the consistency and coherence that A Momentary Lapse Of Reason had lacked.

What’s more, Gilmour went to great lengths to ensure that The Division Bell was genuinely a group album. Mason, who on its predecessor had shared drum duties with machines and Carmine Appice, was back firmly in the driving seat. Perhaps even more significantly, Rick Wright – sacked by Waters during The Wall and reduced to a salaried session man on subsequent Floyd projects – was fully rreinstated. His photo hadn’t even been included on A Momentary Lapse Of Reason but on The Division Bell, he’s credited as co-writer on five tracks, and on the standout “Wearing The Inside Out” takes his first lead vocal since Dark Side Of The Moon.

The empathy between his keyboards and Gilmour’s guitar – heard to best effect on the instrumentals “Cluster One” and “Marooned” – is at the album’s musical heart. It all feels very reassuring. Bob Ezrin, who had produced The Wall, was back at the helm and Dick Parry, whose sax playing had graced Dark Side Of The Moon and Wish You Were, returned for the first time in almost 20 years for “Wearing the Inside Out”. All of these elements meant The Division Bell sounded more like a classic Floyd record than 1983’s The Final Cut, Waters’ swansong with the band.

Certainly, Gilmour’s U2 imitation on “Take It Back” was a mistake and the sampling of Stephen Hawking’s voice on “Keep Talking” doesn’t convince. But they’re rare blemishes: the likes of “What Do You Want From Me” with its “Comfortably Numb”-style guitar solo, the ethereal “Poles Apart” with its inventive Michael Kamen orchestration and the magisterially doomy ballad “High Hopes” proved not only that there could be life after Waters but also ensured that Pink Floyd’s – apparently final – studio album saw them go out on a high.

Lyrically it’s tempting to read the album’s themes of ruptured communication as a broadside against Waters, and “Lost for Words”, as Gilmour’s “How Do You Sleep”, when he sings: “So I open my door to my enemies/And I ask could we wipe the slate clean/But they tell me to please go fuck myself/You know you just can’t win”. The references to “the day the wall came down” on “A Great Day For Freedom” may have been about the reunification of Germany but might also be interpreted as another sideswipe at Waters. And who can Gilmour be addressing but Waters in “Poles Apart” in acid lines such as “Hey you, did you ever realise what you’d become?” Gilmour has diplomatically denied that any of The Division Bell is aimed at his former colleague. Waters can be forgiven if he remains unconvinced by such protestations.

On its release The Division Bell went to number one on both sides of the Atlantic, Floyd’s first chart-topper in America in 15 years. Yet it was poorly received by critics and dismissed as an anachronism. Pink Floyd seemed at best an irrelevance and at worst a bunch of middle-aged millionaires engaged in a bitching match over the division of the spoils. Gallagher versus Albarn offered a far more titillating street fight than the High Court battles of Gilmour versus Waters. Twenty years on, the passage of time now allows for a rather different judgment.

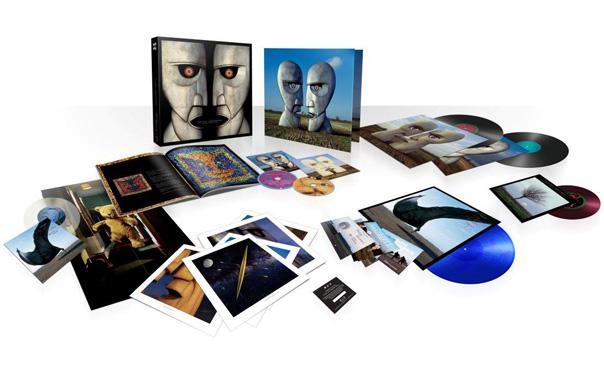

EXTRAS: 7/10 The six-disc box set contains no actual new music, focusing instead on an audiophile smorgasbord: an audio CD of the 2011 remaster; a remastered double vinyl copy of the original album; and a Blu-ray disc with previously unreleased 5.1 mix, HD audio mix and video for “Marooned” directed by Aubrey Powell. There is also a one-sided blue vinyl 12” containing “High Hopes”/“Keep Talking”/“One Of These Days (Live)”, a red vinyl 7” single (“Take It Back”/“Astronomy Domine (Live)” and a clear vinyl 7”single (“High Hopes/ “Keep Talking”), plus a 24-page booklet and five art prints designed by Hipgnosis/StormStudios. There is also a new vinyl remaster, but no new CD: the 2011 remastered single CD remains in catalogue.

Nigel Williamson