Hawley's fourth album, Cole's Corner, attracted a Mercury nomination, and established the former Pulp/Longpigs sideman as a late contender for Most Promising Newcomer of 1962. Happily, Lady's Bridge offers no great departures from that record's melancholy mood. It, too, sounds as if it has been decanted from a time when disc jockeys wore dinner jackets, and a gentleman in trouble might soothe his troubled heart with a stroll along the banks of the canal. Not that Hawley needs to change. While he still sings like a kinder, sadder Jarvis Cocker would, perhaps after an encounter with his karaoke uncle, he does it with such sincerity that it seems churlish to resist. Actually, he doesn't sing. He croons. The opening "Valentine", with a guitar strummed in the manner of a tolling bell, and cataclysmic strings on loan from The Walker Brothers, is a delicate and devastating pop song, in which a man struggles through the night to the dawnin' (rhymes with "warning in your eyes"), whereupon the tune swells to the point where only Roy Orbison could bring it home alive. As before, the album's title refers to a Sheffield landmark, but Hawley's concerns are universal. Mostly, he maps the faultlines between loneliness and love. Occasionally (the skiffly "Serious") he is upbeat. "The Streets Are Ours" is almost paternal, with Hawley rejecting the soulless people who "make our TVs blind us/from our vision and our goals." "Dark Road" is a defiant cowboy song and - if this really was 1962 - would benefit from being covered by Lee Marvin. But fear not. Mostly, Hawley is woeful. There are songs of ships on troubled oceans, suns which refuse to shine, and rivers (that rhyme with "forgive her"). The loveliest of these is "Roll River"; a gentle melody floated over honky-tonk piano and majestic strings. It sounds so peaceful and untroubled that you almost don't notice that the singer is busy yearning for death. Alastair McKay UNCUT: Where did the album title come from? RICHARD HAWLEY: Lady's Bridge is in Sheffield. It's a really ancient fording point. It was originally built out of wood in 1140 by a Norman Prince, and it was rebuilt after the great Sheffield floods of the 1840's.The title is a metaphor too; it's about leaving the past behind. UNCUT: Did you feel a pressure to succeed following the success of Coles Corner? RICHARD HAWLEY: In the studio, it was my job to make sure no one felt that pressure. In the end, you've got to make the music you want to make. It will hurt if people hate it, but I've got no choice. UNCUT: How do you write the songs? RICHARD HAWLEY: They mostly come to me when I'm distracted. A few times on tour I'd tell the bus driver to pull over. I would then run out on to the hard shoulder and sing a tune into a dictaphone. I can't drive, but I can certainly drive people crackers! Interview: Paul Moody

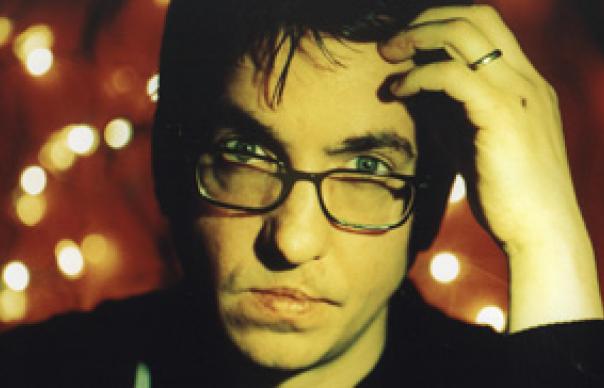

Hawley’s fourth album, Cole’s Corner, attracted a Mercury nomination, and established the former Pulp/Longpigs sideman as a late contender for Most Promising Newcomer of 1962. Happily, Lady’s Bridge offers no great departures from that record’s melancholy mood. It, too, sounds as if it has been decanted from a time when disc jockeys wore dinner jackets, and a gentleman in trouble might soothe his troubled heart with a stroll along the banks of the canal.

Not that Hawley needs to change. While he still sings like a kinder, sadder Jarvis Cocker would, perhaps after an encounter with his karaoke uncle, he does it with such sincerity that it seems churlish to resist. Actually, he doesn’t sing. He croons. The opening “Valentine”, with a guitar strummed in the manner of a tolling bell, and cataclysmic strings on loan from The Walker Brothers, is a delicate and devastating pop song, in which a man struggles through the night to the dawnin’ (rhymes with “warning in your eyes“), whereupon the tune swells to the point where only Roy Orbison could bring it home alive.

As before, the album’s title refers to a Sheffield landmark, but Hawley’s concerns are universal. Mostly, he maps the faultlines between loneliness and love. Occasionally (the skiffly “Serious”) he is upbeat. “The Streets Are Ours” is almost paternal, with Hawley rejecting the soulless people who “make our TVs blind us/from our vision and our goals.” “Dark Road” is a defiant cowboy song and – if this really was 1962 – would benefit from being covered by Lee Marvin.

But fear not. Mostly, Hawley is woeful. There are songs of ships on troubled oceans, suns which refuse to shine, and rivers (that rhyme with “forgive her“). The loveliest of these is “Roll River”; a gentle melody floated over honky-tonk piano and majestic strings. It sounds so peaceful and untroubled that you almost don’t notice that the singer is busy yearning for death.

Alastair McKay

UNCUT: Where did the album title come from?

RICHARD HAWLEY: Lady’s Bridge is in Sheffield. It’s a really ancient fording point. It was originally built out of wood in 1140 by a Norman Prince, and it was rebuilt after the great Sheffield floods of the 1840’s.The title is a metaphor too; it’s about leaving the past behind.

UNCUT: Did you feel a pressure to succeed following the success of Coles Corner?

RICHARD HAWLEY: In the studio, it was my job to make sure no one felt that pressure. In the end, you’ve got to make the music you want to make. It will hurt if people hate it, but I’ve got no choice.

UNCUT: How do you write the songs?

RICHARD HAWLEY: They mostly come to me when I’m distracted. A few times on tour I’d tell the bus driver to pull over. I would then run out on to the hard shoulder and sing a tune into a dictaphone. I can’t drive, but I can certainly drive people crackers!

Interview: Paul Moody