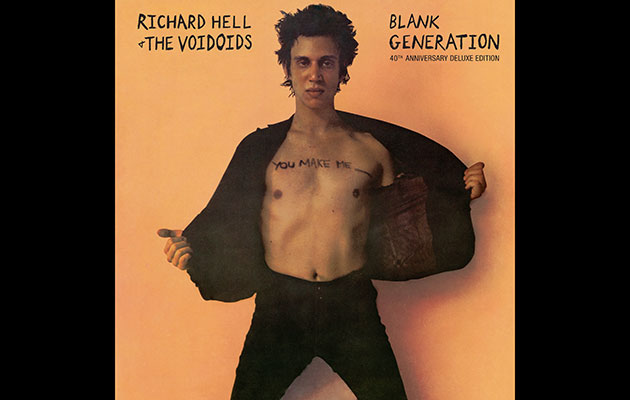

Richard Hell was everywhere, back then. Versions of him, anyway. This was 1977, punk well under way, and the look that was common among bands and fans from the King’s Road to East Kilbride was his. It was a tattered look that, worn by Hell, hinted at a kind of soiled dandyism. It included hair that appeared to have been cut using a lawnmower with most of its blades missing, T-shirts that seemed to have been shredded by shrapnel, sometimes held together by safety pins, or smeared with slogans. Any old jacket would do, as long as it looked like it had recently been taken from a bloated corpse, washed up on an estuary sandbank. In 1977, this was a new way of dressing, much gawked at. Hell had looked like this for years, the music he’d been making for almost as long just as frayed, provocative and influential.

Like Dylan before him, he blew into New York from the American heartland, Kentucky via Delaware, high on poetry, music and himself. He was 17 and people who knew him still called him Richard Meyers. It was just after Christmas, 1966. Patti Smith made a similar journey, Philadelphia via New Jersey, six months later. They found low-paid work, lived in the same kinds of dingy, cold-water digs, wrote poems, Meyers publishing his own magazine. In their shared sense of destiny, they were where they were meant to be, at the centre of things that hadn’t quite happened yet, that would be indelibly marked by their respective interventions, Meyers and Smith emerging as key players in the New York punk and art scene that grew out of and around the Bowery music club CBGB and the Lower East Side.

In February 1971, Smith appeared at St Mark’s Church, performing for the first time with Lenny Kaye on guitar. According to Meyers, who was in the audience, he’d also been thinking about mixing poetry and music, and with Tom Miller, a fellow misfit he’d met at boarding school in Delaware, he formed The Neon Boys, the pair charismatically renaming themselves Richard Hell and Tom Verlaine. The increasingly accomplished Verlaine played lead guitar, with Hell on rudimentary bass. With the addition of second guitarist Richard Lloyd, they became Television and their music more complex under Verlaine’s dictatorial leadership. Sidelined, Hell left Television in March 1975. A week later, he joined former New York Dolls Johnny Thunders and Jerry Nolan in The Heartbreakers. They played the aggressive, sneering rock he loved, but their songs lacked Television’s lyrical finesse.

Early in 1976, he quit and formed The Voidoids, recruiting drummer Marc Bell from Wayne County’s band, guitarists Ivan Julian, bizarrely a veteran at 21 of UK pop act The Foundations, and Robert Quine, a brilliant guitarist but a difficult man who committed suicide in 2004. He was 34, prematurely bald, obsessed with The Velvet Underground, free jazz and ’50s rock’n’roll. He dressed in conservative slacks, button-down shirts and sports coats and hadn’t played in a band since 1968. However, his coruscating lead lines and explosive solos quickly became one of the band’s defining sounds. The Voidoids formed in June 1976, played their first gig in November and by the start of 1977 were in the studio, recording their first album, Blank Generation.

Of the great debut albums by bands from the CBGB scene, you might listen to Television’s Marquee Moon and think of bat caves made of ice, lit by neon. On their debut album, the Ramones sounded like they’d been strapped to the nose cone of a ballistic missile and blasted into space. Talking Heads: 77 was replete with jittery impulses, uptight and tense. Patti Smith’s Horses, meanwhile, sounded like something beset by bad weather, hoarse incantations made on a windswept beach under a sky best described as glowering. Blank Generation, finally released in November 1977, sounded by comparison grubby, dishevelled, like it had been recorded in an alley strewn with broken glass, beer cans and dead cats.

It was actually recorded at Electric Lady in Greenwich Village, and produced by industry veteran Richard Gottehrer, co-founder of Sire and notably part of the production team who’d made garage-band classic “I Want Candy”, which they released as The Strangeloves, good enough credentials at the time for Hell. Blank Generation was finished by the end of March. But by then Hell had serious reservations about the record. When Sire announced its release would be delayed, he insisted on re-recording it, replacing seven of the 10 tracks with new versions recorded at Plaza Sound. Listening to the Electric Lady versions of tracks from the album on the bonus disc of this anniversary reissue (which also includes five tracks recorded live at their debut performance, the original Ork Records version of “Another World” and the band’s last, one-off, recording, 2000’s “Oh”), you can hear that Hell’s instincts were right. The Plaza Sound versions are sharper, more dynamic, harder-edged, more abandoned, the band capable of making quite a racket, Julian and Quine’s guitars combining in ways that make them sound occasionally like Antennae Jimmy Semens and Zoot Horn Rollo on Trout Mask Replica, Hell yelping over them like something with a tail, caught in a trap. On the brief, savage solos he takes, Quine sounds like he’s handcuffed to lightning.

There are hiccupping punk broadsides like “Liars Beware”, “New Pleasure” and “Who Says?”, and “Down At The Rock And Roll Club” has a ramshackle air that anticipates The Replacements, but as Hell says proudly, the album’s not all crude heckle, frenzied accusation and pop-eyed bile. “Betrayal Takes Two” is a woozy country-doo-wop mash-up, “The Plan” a pretty anticipation of lovely Babyshambles songs like “In Love With A Feeling” and “Loyalty Song”. There’s also an eerie take on John Fogerty’s “Walking On The Water”, originally recorded by Fogerty’s pre-Creedence band, The Golliwogs, an obscurity suggested by Quine. Even nominal punk anthems “Love Comes In Spurts” and “Blank Generation” don’t fully conform to punk’s typical roar. “Love Comes In Spurts” is usually described as an anti-love song, but beneath its surface grubbiness it’s a teenage lament as touching in its way as a Brill Building ballad. Similarly, “Blank Generation” is barely as savage as the song it famously inspired, the Sex Pistols’ “Pretty Vacant”. Written as a parody of a ’50s novelty song called “I Belong To The Beat Generation”, it lampoons self-regarding hippie communality as wryly as Neil Young’s “Roll Another Number For The Road”, from Tonight’s The Night, an album whose raw intensity is also recalled on album closer “Another World”, eight minutes of personal exorcism. Hell describes it as “hysterical to the point of mysticism”. It ends with him hoarse, hacking, coughing, spent.

“By then I was wiped out,” Hell says, thinking about it 40 years later. “All I had left to hang on to was my feelings. I gave it everything I had. We all did.”