Richard Thompson is not, he admits, a sentimental man. Nevertheless, even he must be secretly moved by the fact that this summer marks his fortieth year in music. On May 27, 1967, Fairport Convention played their first gig in a Golders Green church hall, with Thompson – a gangling, diffident 18-year-old – on lead guitar. Three years later, Thompson had left the band. But while most of his bandmates soon decided that frothing tankards and stout yeomanry could fill a career, Thompson embarked on a more bloody-minded artistic journey. Sweet Warrior is roughly his 16th solo album, and he sounds more like a loner - intense, precise, impervious to fashion - than ever. Save “Francesca”, a stiff nod to reggae, Thompson hasn’t radically altered his style. These remain, ostensibly, rock songs underpinned by the cadences of folk, delivered by a stern and occasionally rather wry man who plays guitar with a fearsome penetrative clarity. If Neil Young is rock’s quintessential sloucher, then Thompson is his polar opposite, the uptight maestro, nerves as taut and tuned as his guitar strings. “Bad Monkey” may be jaunty, a Caledonian swing tune inhabited by the spirit of Lord Rockingham’s XI. But every time the honking saxes appear to gain the upper hand, Thompson hoves back into view, spitting out solos that have the bent vigour of Roger McGuinn on “Eight Miles High”. 2005’s lovely solo acoustic set, Front Parlour Ballads, saw him pondering British identity from his exile in LA. But this one is a fiercer and less suburban record, predicated on conflict, both between countries and lovers. “Dad’s Gonna Kill Me” is a bitter stand-out, written from the perspective of a GI stationed in Iraq. “Out in the desert there’s a soldier lying dead/ Vultures pecking the eyes out of his head,” he hisses, with a stentorian ardour that’s oddly similar to Nick Cave. Thompson can still be tender, though, and the way “Take Care The Road You Choose” gracefully unravels, with the guitar teasing emotional verities out of a buttoned-up stoic, bears comparison with his best songs from the Richard & Linda era. When Thompson sings about pursuing a vision and “not looking for ghosts behind me,” it works as a metaphor for his own brilliant career, too. The Liege & Lief-era Fairports will reunite briefly this month, but Thompson – and only Thompson – doesn’t need to relive any past glories. JOHN MULVEY Q&A with Richard Thompson UNCUT: Why a fuller rock record this time? RICHARD THOMPSON: I kinda collect songs in piles. I have an acoustic pile, but this pile had grown sufficiently over the past couple of years. They’re the best songs I’ve got at the moment. You recently worked with Rufus Wainwright, who said he was frightened of you because you were so “fiercely heterosexual”. That’s quite funny. I’ve known Rufus both as Loudon’s son and as Teddy’s friend. I don’t know whether to be flattered. I am what I am. . . well, I’m heterosexual. You’re reuniting with the 1969 line-up of Fairport Convention to play Liege And Lief at the Cropredy festival in August. That’s what they say. It’ll be strange, but at the same time familiar. It’s a bit like riding a bike, that album. I could play it now with no rehearsal. It’s also the band’s 40th anniversary. Yeah [sighs]. I was really depressed at the tenth anniversary, so 40 is just off the scale. How can it be 40 years? It’s insane. You never strike me as a particularly sentimental man. Well I’m not really, no. I don’t like nostalgia. I suppose one of the ways to keep creating is to not look back. . . too often.

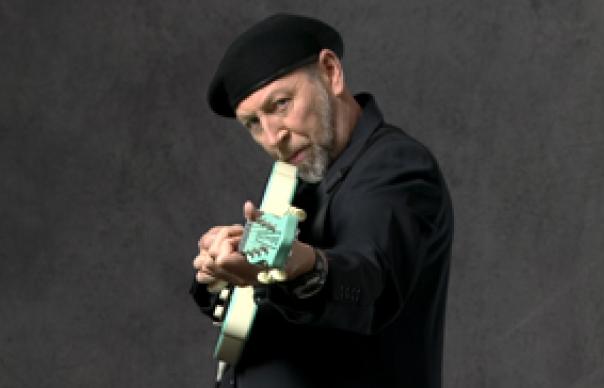

Richard Thompson is not, he admits, a sentimental man. Nevertheless, even he must be secretly moved by the fact that this summer marks his fortieth year in music. On May 27, 1967, Fairport Convention played their first gig in a Golders Green church hall, with Thompson – a gangling, diffident 18-year-old – on lead guitar.

Three years later, Thompson had left the band. But while most of his bandmates soon decided that frothing tankards and stout yeomanry could fill a career, Thompson embarked on a more bloody-minded artistic journey.

Sweet Warrior is roughly his 16th solo album, and he sounds more like a loner – intense, precise, impervious to fashion – than ever.

Save “Francesca”, a stiff nod to reggae, Thompson hasn’t radically altered his style. These remain, ostensibly, rock songs underpinned by the cadences of folk, delivered by a stern and occasionally rather wry man who plays guitar with a fearsome penetrative clarity.

If Neil Young is rock’s quintessential sloucher, then Thompson is his polar opposite, the uptight maestro, nerves as taut and tuned as his guitar strings. “Bad Monkey” may be jaunty, a Caledonian swing tune inhabited by the spirit of Lord Rockingham’s XI. But every time the honking saxes appear to gain the upper hand, Thompson hoves back into view, spitting out solos that have the bent vigour of Roger McGuinn on “Eight Miles High”.

2005’s lovely solo acoustic set, Front Parlour Ballads, saw him pondering British identity from his exile in LA.

But this one is a fiercer and less suburban record, predicated on conflict, both between countries and lovers. “Dad’s Gonna Kill Me” is a bitter stand-out, written from the perspective of a GI stationed in Iraq. “Out in the desert there’s a soldier lying dead/ Vultures pecking the eyes out of his head,” he hisses, with a stentorian ardour that’s oddly similar to Nick Cave.

Thompson can still be tender, though, and the way “Take Care The Road You Choose” gracefully unravels, with the guitar teasing emotional verities out of a buttoned-up stoic, bears comparison with his best songs from the Richard & Linda era. When Thompson sings about pursuing a vision and “not looking for ghosts behind me,” it works as a metaphor for his own brilliant career, too. The Liege & Lief-era Fairports will reunite briefly this month, but Thompson – and only Thompson – doesn’t need to relive any past glories.

JOHN MULVEY

Q&A with Richard Thompson

UNCUT: Why a fuller rock record this time?

RICHARD THOMPSON: I kinda collect songs in piles. I have an acoustic pile, but this pile had grown sufficiently over the past couple of years. They’re the best songs I’ve got at the moment.

You recently worked with Rufus Wainwright, who said he was frightened of you because you were so “fiercely heterosexual”.

That’s quite funny. I’ve known Rufus both as Loudon’s son and as Teddy’s friend. I don’t know whether to be flattered. I am what I am. . . well, I’m heterosexual.

You’re reuniting with the 1969 line-up of Fairport Convention to play Liege And Lief at the Cropredy festival in August.

That’s what they say. It’ll be strange, but at the same time familiar. It’s a bit like riding a bike, that album. I could play it now with no rehearsal.

It’s also the band’s 40th anniversary.

Yeah [sighs]. I was really depressed at the tenth anniversary, so 40 is just off the scale. How can it be 40 years? It’s insane.

You never strike me as a particularly sentimental man.

Well I’m not really, no. I don’t like nostalgia. I suppose one of the ways to keep creating is to not look back. . . too often.