A few years ago I interviewed Rod Stewart and, after a few preliminaries, such as Rod leading the LA Exiles football team on a conga through the corridors of a Glasgow hotel, I asked him why he didn’t make more records like Gasoline Alley or Every Picture Tells A Story. It wasn’t a hostile question. I was merely curious why a singer who was capable of such brilliance had settled for less in the later part of his career. Maybe Rod understood the implication, maybe he didn’t. He was floating on a river of brandy, so he didn’t get angry. Instead, he looked at me with utter bemusement, and said something to the effect that he couldn’t make records like that any more as the musicians he’d played with back then were all dead. Never mind that this wasn’t true: Stewart didn’t seem able to compute that this wasn’t a question about particular players. The point was that the beautiful spontaneity of his early records had been shrink-wrapped in Spandex on his later work. True, many of his biggest hits came after he settled for being a cartoon, but the music didn’t lie. Put the tender poetry of “Mandolin Wind” next to the hormonal Jaggerisms of “Hot Legs”. There’s no contest. All of which makes the timespan of this studio sessions/demos/rarities compilation an oddity. The great years were 1969-73. But 1998 takes Stewart beyond the Britt Ekland-era, through slump, the 1993 Unplugged revival, and back into the wilderness, before his current rebirth as a heritage crooner. Presumably, the logic is contractual. And it’s not as if Stewart hasn’t already been anthologised: the first two discs of the four-disc Storyteller box made an eloquent case for Rod’s talent, beginning with a 1964 recording of “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl”. But actually, this set proves two things. First, the fragile spontaneity of those early recordings was anything but. There’s an early version of “Maggie May” here, recorded before the song had a chorus, on which the lyric includes the line “I don’t need to tell ya/That you look like a fella/But I’ll kick your head in one of these days.” Thankfully, on the finished version of the song, Stewart vented the anger of the jilted narrator in more measured tones. It’s clear, listening to the rough sketch of “You Wear It Well” – on which Stewart resorts to humming before the song breaks down – that the ramshackle beauty of the singer’s early recordings was the result of much hard labour. It’s also apparent that Stewart himself was the catalyst for this, and acted as musical director. The lovely, lazy rocker, “Think I’ll Pack My Bags” (later to become “Mystifies Me” on a Ron Wood LP) has Stewart breaking from singing to coax Wood’s guitar through the middle eight. (At times, these informalities are a distraction. After a soulful “I’d Rather Go Blind”, Stewart suddenly exclaims: “Fire extinguisher!”) The less-polished performances of the later material show that Stewart’s genius was never entirely absent. There’s a lovely version of “You’re In My Heart” and an extraordinary “Thunderbird”, on which the sound levels are wayward, but the rasping vocal is pulled along by a rough gospel arrangement. “Sweet Surrender” is similarly fine, with Rod’s voice mixed high against saucy Southern guitar, as the old romantic croons “You ruffle my ego, but not my bed.” Even “Sailing” – a song nullified by over-exposure – is revealed here as a gospel hymn, with the singer preparing to pass over the river of death. At moments like this – if you can ignore the synth crimes – the thread of continuity in Stewart’s work is obvious. He might have wanted riches, a train-set and a battery of blondes, but he also wanted to be Sam Cooke. It’s not all good news. Disc Four is dedicated to 1990s’ rarities and is uniformly painful. (Paul Weller fans would do well to avoid Rod’s fight with “The Changingman”.) And then, just as despair takes hold, Rod offers up a sweet, soft interpretation of John Martyn’s “May You Never”. The arrangement is understated – no disco flourishes – and he sings it well. The cheek of the younger Rod is replaced by maturity and contentment. It’s a signpost to what might have been. ALISTAIR MCKAY Latest and archive album reviews on Uncut.co.uk Latest music and film news on Uncut.co.uk

A few years ago I interviewed Rod Stewart and, after a few preliminaries, such as Rod leading the LA Exiles football team on a conga through the corridors of a Glasgow hotel, I asked him why he didn’t make more records like Gasoline Alley or Every Picture Tells A Story. It wasn’t a hostile question. I was merely curious why a singer who was capable of such brilliance had settled for less in the later part of his career.

Maybe Rod understood the implication, maybe he didn’t. He was floating on a river of brandy, so he didn’t get angry. Instead, he looked at me with utter bemusement, and said something to the effect that he couldn’t make records like that any more as the musicians he’d played with back then were all dead.

Never mind that this wasn’t true: Stewart didn’t seem able to compute that this wasn’t a question about particular players. The point was that the beautiful spontaneity of his early records had been shrink-wrapped in Spandex on his later work. True, many of his biggest hits came after he settled for being a cartoon, but the music didn’t lie. Put the tender poetry of “Mandolin Wind” next to the hormonal Jaggerisms of “Hot Legs”. There’s no contest.

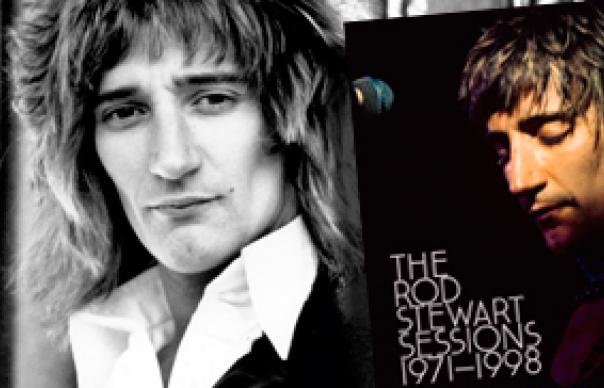

All of which makes the timespan of this studio sessions/demos/rarities compilation an oddity. The great years were 1969-73. But 1998 takes Stewart beyond the Britt Ekland-era, through slump, the 1993 Unplugged revival, and back into the wilderness, before his current rebirth as a heritage crooner. Presumably, the logic is contractual. And it’s not as if Stewart hasn’t already been anthologised: the first two discs of the four-disc Storyteller box made an eloquent case for Rod’s talent, beginning with a 1964 recording of “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl”.

But actually, this set proves two things.

First, the fragile spontaneity of those early recordings was anything but. There’s an early version of “Maggie May” here, recorded before the song had a chorus, on which the lyric includes the line “I don’t need to tell ya/That you look like a fella/But I’ll kick your head in one of these days.” Thankfully, on the finished version of the song, Stewart vented the anger of the jilted narrator in more measured tones.

It’s clear, listening to the rough sketch of “You Wear It Well” – on which Stewart resorts to humming before the song breaks down – that the ramshackle beauty of the singer’s early recordings was the result of much hard labour. It’s also apparent that Stewart himself was the catalyst for this, and acted as musical director.

The lovely, lazy rocker, “Think I’ll Pack My Bags” (later to become “Mystifies Me” on a Ron Wood LP) has Stewart breaking from singing to coax Wood’s guitar through the middle eight. (At times, these informalities are a distraction. After a soulful “I’d Rather Go Blind”, Stewart suddenly exclaims: “Fire extinguisher!”)

The less-polished performances of the later material show that Stewart’s genius was never entirely absent. There’s a lovely version of “You’re In My Heart” and an extraordinary “Thunderbird”, on which the sound levels are wayward, but the rasping vocal is pulled along by a rough gospel arrangement.

“Sweet Surrender” is similarly fine, with Rod’s voice mixed high against saucy Southern guitar, as the old romantic croons “You ruffle my ego, but not my bed.” Even “Sailing” – a song nullified by over-exposure – is revealed here as a gospel hymn, with the singer preparing to pass over the river of death. At moments like this – if you can ignore the synth crimes – the thread of continuity in Stewart’s work is obvious. He might have wanted riches, a train-set and a battery of blondes, but he also wanted to be Sam Cooke.

It’s not all good news. Disc Four is dedicated to 1990s’ rarities and is uniformly painful. (Paul Weller fans would do well to avoid Rod’s fight with “The Changingman”.) And then, just as despair takes hold, Rod offers up a sweet, soft interpretation of John Martyn’s “May You Never”. The arrangement is understated – no disco flourishes – and he sings it well. The cheek of the younger Rod is replaced by maturity and contentment. It’s a signpost to what might have been.

ALISTAIR MCKAY