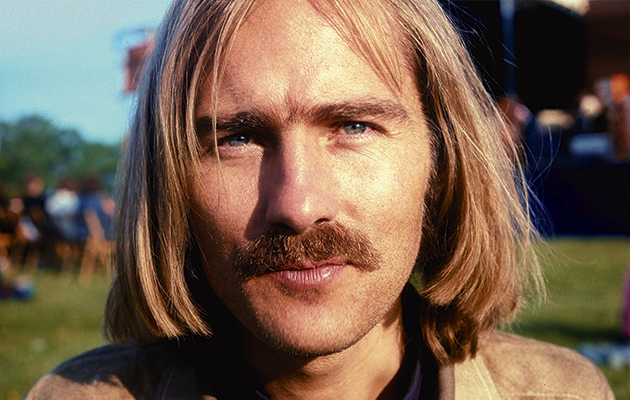

Half a century ago, Roy Harper – then very much a beautiful, rambling mess, to paraphrase one of his songs – accidentally wrote what could be a perfect epitaph. “They all tried to make a someone out of me,” he sang on “Circle”, “and never saw that I could only be me.” Few songwriter...

Half a century ago, Roy Harper – then very much a beautiful, rambling mess, to paraphrase one of his songs – accidentally wrote what could be a perfect epitaph. “They all tried to make a someone out of me,” he sang on “Circle”, “and never saw that I could only be me.”

Few songwriters, it seems, have embodied our ideal of the driven, tortured artist quite as closely as Harper, a man whose talents are matched only by his self-assurance and extreme aversion to compromise. To escape an unhappy adolescence, he joined the Air Force but, being allergic to rules and structures, soon feigned insanity. This strategy succeeded in getting him discharged, though with the added side-effect of incarceration and a course of electroshock therapy.

After exiting Lancaster Moor Mental Hospital through a bathroom window and busking through North Africa and Europe, by the mid-’60s Harper had ended up in London’s fertile folk scene, centred around Les Cousins on Soho’s Greek Street. What should have been a natural home, though, merely seemed to cast him in even starker contrast to his counterparts – he played acoustic guitar, but was uninterested in the folk or blues plied by the likes of The Watersons or Alexis Korner, the psych-folk of the Incredible String Band, or the compact songs of Paul Simon or Jackson C Frank, preferring instead to weave confrontational, wordy songs influenced by the ambition of classical music and avant-garde jazz, and poetry from the Beats and Romantics.

An outsider to the outsiders, a freak among the freaks, Harper nevertheless found himself signed to Columbia in 1967 for his second album, Come Out Fighting Ghengis Smith, which is now being reissued as a tenderly remastered 180g LP along with two of Harper’s electric records. On first glance they seem a strange trio to release together, when Folkjokeopus, Valentine and The Sophisticated Beggar remain to be remastered; yet while Stormcock, Flat Baroque & Berserk and Lifemask (all reissued in 2016) are the singer’s stone-cold classics, Ghengis, HQ and Bullinamingvase are three of his more overlooked outliers, and thus worth revisiting no matter how arbitrary their reappearance right now might be.

50 years on, Come Out Fighting Ghengis Smith sounds both of its time and completely out of it, in more ways than one – “Freak Suite” and “You Don’t Need Money”, paeans to the hippies of Soho and the Mediterranean, drip with patchouli and fugs of dope smoke, but Harper’s melismatic vocals and lyrics (“I’ll moonbathe on your grassy banks/Walk the ever endless planks…”) are astonishing heard through cleaned-up production. More timeless are “All You Need Is” and “What You Have”, boasting some of Harper’s most serpentine finger-picking and delicate arrangements from Keith Mansfield and producer Shel Talmy.

While Columbia were banking on Harper to ape his Cousins alumnus Paul Simon and write some hits, he instead gave them an extraordinary, experimental second side: “Circle” looked back on Harper’s difficult childhood over 11 minutes, and even incorporated an imaginary discussion between the singer and his father, both played by Roy. Meanwhile the harrowing title track, now with newly overdubbed bass, ran for nine minutes and ended with Harper spouting an unhinged poem and impersonating Dylan; an apt reference, seeing as Bob was one of the only songwriters in the mid-’60s pushing things as far as Harper.

Scroll on to 1975, and Harper, emboldened by Stormcock and Lifemask, had enlisted a crack team of musicians, including John Paul Jones, Bill Bruford, David Gilmour and Chris Spedding, to record his most confident record. This was an annus mirabilis for widescreen rock LPs, from Physical Graffiti and Wish You Were Here (the latter featuring Harper) to Born To Run, and HQ is similarly grand. Swaggering opener “The Game (Parts 1-5)” introduces Harper as rock star, lithe as Plant and furious as Waters, yet here attempting to analyse millennia of human civilisation in just 14 minutes. With its deconstructions of social, economic and religious structures, and its criticism of “the prophets of freedom”, “The Game”’s remit is akin to squeezing Bleak House into a few tweets, yet it succeeds gloriously through sheer force of will.

Elsewhere, Harper takes aim at the Church (“Incestuous exploiters of a catalogue of hate”) on “The Spirit Lives”, while the atmospheric “Hallucinating Light” is lifted by Spedding’s limber lead guitar.

HQ closes with “When An Old Cricketer Leaves The Crease”, one of Harper’s most enduring and affecting pieces. If Ghengis Smith captured Harper in stoned flow, spewing out ideas in all directions, then “Cricketer”, buoyed by the Grimethorpe Colliery Band, marks the point when he learnt to distil his thickets of thought down to their essence.

The following year, Harper’s closest analogue Al Stewart would hit big with Year Of The Cat, but Harper remained too uncompromising and complex to manage a similar jump to the mainstream. His star-studded HQ band, Trigger, had disintegrated, and Harper had dramatically lost confidence after a dispiriting set at Knebworth in July 1975. Even cameos from the McCartneys, Alvin Lee and Ronnie Lane on his 1977 single “One Of Those Days In England Part 1” couldn’t bring him the success he was sure he deserved. The accompanying Bullinamingvase LP was another outstanding effort, if slightly tainted by the glossy production of the era; still, the jazzy, meditative “These Last Days” recaptured 1974’s bittersweet Valentine, while “Cherishing The Lonesome” nimbly mixed the modal picking of Stormcock with HQ’s electric bombast.

Like many of his admiring peers, Harper appeared to atrophy as punk hit and the ’80s beckoned. In the years to come, he would endure lows – historic sexual abuse allegations that, despite acquittals or dropped charges, lost Harper all his savings – but also returns to form with 2000’s The Green Man and 2013’s Man Or Myth, and a renewed appreciation of his work by younger musicians including Joanna Newsom, Fleet Foxes, Jim O’Rourke and Jonathan Wilson.

Today, aged 76 and living quietly in rural Cork, Harper remains the eternal outsider, the passing years sanding none of the rough edges or poetic refractions from his finest work. Yet his achievements endure, and with this latest set of finely pressed reissues, he’s continuing to tell his singular story.

“I’ll wander just where I please/Through my wallowing dreams with ease,” he sang, presciently, on 1967’s “In A Beautiful Rambling Mess”. “And I’ll still be here after pancake doomsday/What a beautiful rambling mess we live…”