Sometimes what is most exotic is what you unearth in your own back yard – or at least in your own recent cultural past. After helping put “world music” on the rock’n’roll map with Buena Vista Social Club, Ry Cooder has lately entered the third phase of a career characterised by fascination with pre-rock pop culture: rediscovering America (and Americana) on his most recent albums Chávez Ravine, My Name Is Buddy and now I, Flathead. Leaving Cuba and Timbuktu for the South LA suburbs of Norwalk and South Gate may seem a strange move, but exploring a vanished California seems to have reinvigorated a musician who was always as much archaeologist-anthropologist as singer-writer-guitarist. The historical sweep of Cooder’s SoCal “trilogy” is breathtaking. A short recap for those joining us late. Chávez Ravine examined a shameful episode in LA’s civic history, shining a light on the neglected music of Mex-Angeles. My Name Is Buddy celebrated the political radicalisation of folk and bluegrass. I, Flathead, meanwhile grapples with the blue-collar white California of the ’50s and ’60s by imagining a redneck musician called Kash Buk, and his bar band, The Klowns. “Hot rod cars and country songs,” Cooder notes of the album’s milieu in his press release; “honky tonks and dirty blondes…” There’s plenty of all those here. Kash holds down a residency at the Green Door in Vernon, races dragsters out in the dry desert lakes ’round Ridgecrest and Barstow, and winds up alone on an oxygen tank in an Anaheim trailer. On My Name Is Buddy’s “Three Chords And The Truth”, Cooder revealed that Kash had a fleeting opportunity to join Ray Price’s band; on I, Flathead’s “5000 Country Music Songs” he rues that missed chance but accepts the essential failure of his music and his life. Country’n’western – make that country boogie’n’western swing – sets the essential tone for I, Flathead. Where Buddy hymned Hank Williams, Flathead’s “Johnny Cash” is a brilliant homage to the Man in Black that references his songs (including “Hey Porter”, covered decades ago on Into The Purple Valley) while snaring what they meant to teenage Ry as he dreamed of Big River while gazing out on West Pico Boulevard. “Steel Guitar Heaven” pictures a corner of the afterlife where pedal-steel heroes like Paul Bixby and Joaquin Murphy mellow out with the likes of Spade Cooley against a backdrop of “nylon-pile wall-to-wall carpeting”. Cooley, imprisoned in 1961 for the drunken murder of his second wife, returns later as “Spayed Kooley”, the mutt who keeps Buk company in his dotage. The album is also permeated by the mariachi and ranchero flavours we recall from Chávez. Opener “Drive Like I Never Been Hurt” starts tentatively over a lurching baion beat before cresting in glorious wafts of horns courtesy of Mariachi Los Camperos. “Can I Smoke In Here?” is all loungey guitar and cicada shakers as Kash Buk eases himself onto a barstool and makes overtures to a singularly unimpressed female. The swayingly funky, Latin-infused “Pink-O Boogie”, with Jim Keltner on drums, is a dance that “Republicans just can’t do”. “Fernando Sez” canters along like Lalo Guerrero’s tracks on Chávez, concluding in a long and involved dialogue between a cash-strapped Buk and the song’s eponymous Cadillac dealer. The wistful ranchero of “Filipino Dance Hall Girl” features longtime Cooder mainstay Flaco Jiménez on accordion. With its floating horns and reverbed Fender twang, “Flathead One More Time” recalls Chávez’s spooky “El U.F.O. Cayo” as Kash looks back on his dragster youth and recalls lost pals like “Whiskey Bob down on Thunder Road”. Chávez’s Juliette Commagere makes a reappearance on the coda-like “Little Trona Girl”. The whole album reflects the intermingling of Californian communities, the Los Angeles the world doesn’t know or care to see. These are unique records, mining a fascination with a lost world that few writers save Mike Davis, author of City Of Quartz would even think to look at. They’re dissertations in musical form, ruminations on what’s happened to California and the broader America around it from a man who’s read everyone from Carey McWilliams to Kevin Starr. Yet they’re as mischievously funny, as playfully political, as they are painstakingly scholarly. (Note the slyly sardonic reference to “homeland security” on “Spayed Kooley”.) Plus they sound great: having long disowned the immaculate “Burbank” sound that established him among the Warner Brothers elite in the ’70s, Cooder’s textures now seem to glide and unfurl, his guitars glowing and shimmering through his vintage valve amps. His singing, too, remains infectious: as Kash he sings and indeed speaks in a cod-Southern voice that’s part-Band and part grizzled-country. The accompanying novella is a more than worthy companion-piece to the music. Cooder writes superbly of the strange marginal world of California salt-flat towns like Trona, while the intertwined narratives of Kash Buk, dragster girl Roxanne, and the alien Shakey – not to mention the transcribed interviews with Kash, his stripper ex Donna, and The Klowns’ steel player, Loren “Sonny” Kloer – are absorbing and often sublimely funny. As rivetingly out-of-step with the modern age as Bob Dylan or Tom Waits, Ry Cooder becomes more vital the more he withdraws from the public gaze. Bemused by the dumb celebrity culture we’ve allowed to spread like a plague, he ploughs his own furrow without caring if anyone follows. Along with old Burbank chum Randy Newman, he remains a key presence among the grumpier elder statesmen of West Coast rock. We should salute his irascible talent – and heed his warnings about where our world is headed – while we still can. BARNEY HOSKYNS

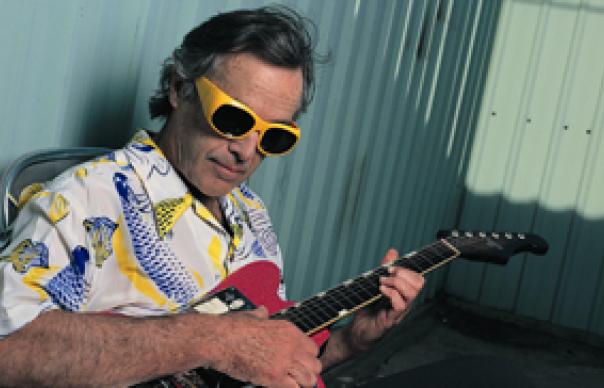

Sometimes what is most exotic is what you unearth in your own back yard – or at least in your own recent cultural past. After helping put “world music” on the rock’n’roll map with Buena Vista Social Club, Ry Cooder has lately entered the third phase of a career characterised by fascination with pre-rock pop culture: rediscovering America (and Americana) on his most recent albums Chávez Ravine, My Name Is Buddy and now I, Flathead.

Leaving Cuba and Timbuktu for the South LA suburbs of Norwalk and South Gate may seem a strange move, but exploring a vanished California seems to have reinvigorated a musician who was always as much archaeologist-anthropologist as singer-writer-guitarist. The historical sweep of Cooder’s SoCal “trilogy” is breathtaking.

A short recap for those joining us late. Chávez Ravine examined a shameful episode in LA’s civic history, shining a light on the neglected music of Mex-Angeles. My Name Is Buddy celebrated the political radicalisation of folk and bluegrass. I, Flathead, meanwhile grapples with the blue-collar white California of the ’50s and ’60s by imagining a redneck musician called Kash Buk, and his bar band, The Klowns.

“Hot rod cars and country songs,” Cooder notes of the album’s milieu in his press release; “honky tonks and dirty blondes…” There’s plenty of all those here.

Kash holds down a residency at the Green Door in Vernon, races dragsters out in the dry desert lakes ’round Ridgecrest and Barstow, and winds up alone on an oxygen tank in an Anaheim trailer. On My Name Is Buddy’s “Three Chords And The Truth”, Cooder revealed that Kash had a fleeting opportunity to join Ray Price’s band; on I, Flathead’s “5000 Country Music Songs” he rues that missed chance but accepts the essential failure of his music and his life.

Country’n’western – make that country boogie’n’western swing – sets the essential tone for I, Flathead. Where Buddy hymned Hank Williams, Flathead’s “Johnny Cash” is a brilliant homage to the Man in Black that references his songs (including “Hey Porter”, covered decades ago on Into The Purple Valley) while snaring what they meant to teenage Ry as he dreamed of Big River while gazing out on West Pico Boulevard.

“Steel Guitar Heaven” pictures a corner of the afterlife where pedal-steel heroes like Paul Bixby and Joaquin Murphy mellow out with the likes of Spade Cooley against a backdrop of “nylon-pile wall-to-wall carpeting”. Cooley, imprisoned in 1961 for the drunken murder of his second wife, returns later as “Spayed Kooley”, the mutt who keeps Buk company in his dotage.

The album is also permeated by the mariachi and ranchero flavours we recall from Chávez. Opener “Drive Like I Never Been Hurt” starts tentatively over a lurching baion beat before cresting in glorious wafts of horns courtesy of Mariachi Los Camperos. “Can I Smoke In Here?” is all loungey guitar and cicada shakers as Kash Buk eases himself onto a barstool and makes overtures to a singularly unimpressed female. The swayingly funky, Latin-infused “Pink-O Boogie”, with Jim Keltner on drums, is a dance that “Republicans just can’t do”.

“Fernando Sez” canters along like

Lalo Guerrero’s tracks on Chávez, concluding in a long and involved dialogue between a cash-strapped Buk and the song’s eponymous Cadillac dealer.

The wistful ranchero of “Filipino Dance Hall Girl” features longtime Cooder mainstay Flaco Jiménez on accordion. With its floating horns and reverbed Fender twang, “Flathead One More Time” recalls Chávez’s spooky “El U.F.O. Cayo” as Kash looks back on his dragster youth and recalls lost pals like “Whiskey Bob down on Thunder Road”. Chávez’s Juliette Commagere makes a reappearance on the coda-like “Little Trona Girl”.

The whole album reflects the intermingling of Californian communities, the Los Angeles the world doesn’t know or care to see.

These are unique records, mining a fascination with a lost world that few writers save Mike Davis, author of City Of Quartz would even think to look at. They’re dissertations in musical form, ruminations on what’s happened to California and the broader America around it from a man who’s read everyone from Carey McWilliams to Kevin Starr.

Yet they’re as mischievously funny, as playfully political, as they are painstakingly scholarly. (Note

the slyly sardonic reference to “homeland security” on “Spayed Kooley”.) Plus they sound great: having long disowned the immaculate “Burbank” sound that established him among the Warner Brothers elite in the ’70s, Cooder’s textures now seem to glide and unfurl, his guitars glowing and shimmering through his vintage valve amps. His singing, too, remains infectious: as Kash he sings and indeed speaks in a cod-Southern voice that’s part-Band and part grizzled-country.

The accompanying novella is a more than worthy companion-piece to the music. Cooder writes superbly of the strange marginal world of California salt-flat towns like Trona, while the intertwined narratives of Kash Buk, dragster girl Roxanne, and the alien Shakey – not to mention the transcribed interviews with Kash, his stripper ex Donna, and The Klowns’ steel player, Loren “Sonny” Kloer – are absorbing and often sublimely funny.

As rivetingly out-of-step with the modern age as Bob Dylan or Tom Waits, Ry Cooder becomes more vital the more he withdraws from the public gaze. Bemused by the dumb celebrity culture we’ve allowed to spread like a plague, he ploughs his own furrow without caring if anyone follows. Along with old Burbank chum Randy Newman, he remains a key presence among the grumpier elder statesmen of West Coast rock. We should salute his irascible talent – and heed his warnings about where our world is headed – while we still can.

BARNEY HOSKYNS