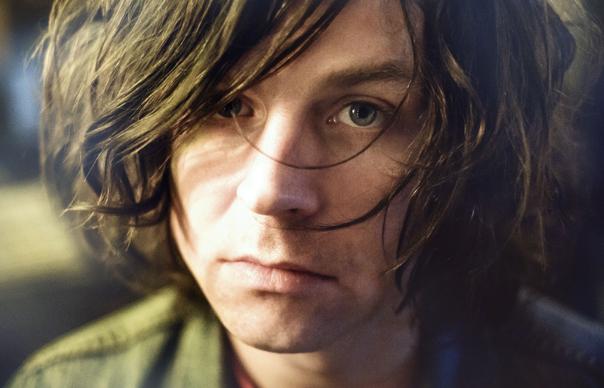

Self-titled, self-produced, and pretty well self-realised... The three years that have elapsed between 2011’s Ashes & Fire and the arrival of this offering are an eternity by Ryan Adams’ extraordinary standards. Including his 2000 solo debut Heartbreaker, the former Whiskeytown singer released thirteen albums in the first decade-and-change of this century – and, incredibly, maintained a quality that almost matched the quantity, give or take the cobbled-together Demolition and the spitefully tossed-off Rock’n’Roll. When any artist returns from hiatus with a self-titled album, they are hustling the listener towards a subtext of “And this, at last, is me.” Ryan Adams radiates precisely this image of first principles being re-embraced. There is none of the (admittedly deftly executed) stylistic tourism of, say, his honky-tonk weeper Jacksonville City Nights, or his conceptual metal opus Orion. Ryan Adams is very much Ryan Adams being Ryan Adams. Which, lest we have forgotten, is a good thing. On song, Adams remains probably the most plausible heir to Bruce Springsteen and Tom Petty – who, possibly not coincidentally, are the two most obvious influences on Ryan Adams. “Gimme Something Good” is pure Petty – a snarling rocker embroidered with sparkling lead guitar and underpinned by Benmont Tench-ish organ. It’s an appropriate tone-setter – the album is largely comprised of similar breezy, mildly belligerent mid-tempo chuggers: “Feels Like Fire”, “Stay With Me”, “Trouble”. Poised as these are, Adams is always at his best when he permits and/or admits vulnerability. “Let Go” is an acoustic trill with a middle eight that reminds of Adams’ gift for finding the deadpan in the prettiest pop melody. “My Wrecking Ball” is simply one of the best things he’s ever recorded – a frail acoustic ballad in the manner of “Why Do They Leave?” or “How Do You Keep Alive”, built on Springstonian automotive metaphor (“Nothing much left in the tank/Somehow this thing still drives”) and shrouded in a “Tunnel Of Love” keyboard (another recurring motif). Adams is still not (quite) 40, and middle age is likely to suit a writer with his gifts for wry reflection: another prodigious golden era is not beyond him. ANDREW MUELLER

Self-titled, self-produced, and pretty well self-realised…

The three years that have elapsed between 2011’s Ashes & Fire and the arrival of this offering are an eternity by Ryan Adams’ extraordinary standards. Including his 2000 solo debut Heartbreaker, the former Whiskeytown singer released thirteen albums in the first decade-and-change of this century – and, incredibly, maintained a quality that almost matched the quantity, give or take the cobbled-together Demolition and the spitefully tossed-off Rock’n’Roll.

When any artist returns from hiatus with a self-titled album, they are hustling the listener towards a subtext of “And this, at last, is me.” Ryan Adams radiates precisely this image of first principles being re-embraced. There is none of the (admittedly deftly executed) stylistic tourism of, say, his honky-tonk weeper Jacksonville City Nights, or his conceptual metal opus Orion. Ryan Adams is very much Ryan Adams being Ryan Adams.

Which, lest we have forgotten, is a good thing. On song, Adams remains probably the most plausible heir to Bruce Springsteen and Tom Petty – who, possibly not coincidentally, are the two most obvious influences on Ryan Adams. “Gimme Something Good” is pure Petty – a snarling rocker embroidered with sparkling lead guitar and underpinned by Benmont Tench-ish organ. It’s an appropriate tone-setter – the album is largely comprised of similar breezy, mildly belligerent mid-tempo chuggers: “Feels Like Fire”, “Stay With Me”, “Trouble”.

Poised as these are, Adams is always at his best when he permits and/or admits vulnerability. “Let Go” is an acoustic trill with a middle eight that reminds of Adams’ gift for finding the deadpan in the prettiest pop melody. “My Wrecking Ball” is simply one of the best things he’s ever recorded – a frail acoustic ballad in the manner of “Why Do They Leave?” or “How Do You Keep Alive”, built on Springstonian automotive metaphor (“Nothing much left in the tank/Somehow this thing still drives”) and shrouded in a “Tunnel Of Love” keyboard (another recurring motif). Adams is still not (quite) 40, and middle age is likely to suit a writer with his gifts for wry reflection: another prodigious golden era is not beyond him.

ANDREW MUELLER