If you thought that the last word in folky period detail was offered by the Coen brothers in their movie Inside Llewyn Davis, then you’ll be fascinated by Chicago’s Ryley Walker. On the cover of his debut album for Tompkins Square, 2014’s agreeably low-key All Kinds Of You, the 25 year old sto...

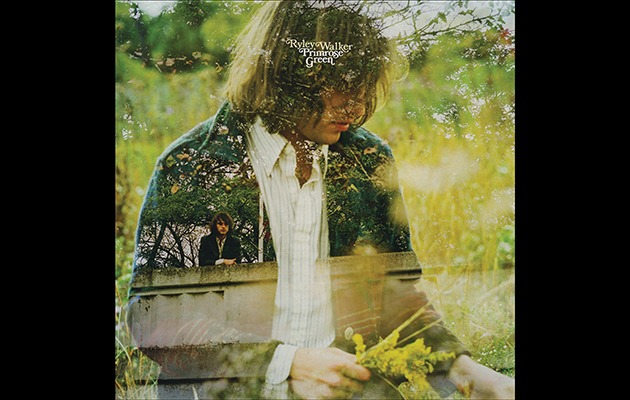

If you thought that the last word in folky period detail was offered by the Coen brothers in their movie Inside Llewyn Davis, then you’ll be fascinated by Chicago’s Ryley Walker. On the cover of his debut album for Tompkins Square, 2014’s agreeably low-key All Kinds Of You, the 25 year old stood smoking a cigarette outside a warehouse, guitar case at his side – the image of the Phil Ochs-style workingman troubadour. On his great second album, he’s pictured in dappled sunlight holding wild flowers, very much the early 1970s Elektra artist, as styled by William S Harvey.

In some ways it’s a perfect representation of the artist – Walker’s new album crests warm currents of jazz, folk and rock as, say, Van Morrison or Tim Buckley did in the period. In others, it’s slightly misleading. While Walker has absorbed these admirably free-roaming influences, this is clearly someone reaching for their essence, on a mission to follow a philosophy rather than to slavishly recreate a mood. A musician whose formative years were spent playing noise in basements rather than perfecting his hammering-on in drop D tuning, there’s a sense that this record represents a snapshot of a restless artist in flux, an evolving creativity. Things weren’t like this last year, and seem highly unlikely to be like this next.

Walker is an appealing character to sign up with. A man able to hold his own among the current wave of instrumental solo guitar performers like Daniel Bachman (with whom he has collaborated), folk guitar is something he loves, but not unreservedly. His wry observation of a scene where guitarists play “with lamps on stage”, casts him as an irreverent, unclubbable character in a world which has its anointed, unchanging gods.

A comment he made on Twitter (“John Fahey still awful jack rose still God”) brought comment from nearly every working guitarist in his field (Nathan Bowles, Cian Nugent, Chris Forsyth and William Tyler), approving or otherwise, as near as any of them are likely to get to a chorus. The other day, he posted a supportive email apparently from John Renbourn, “The more I drink,” the elder statesman bibulously professed, “the smoker I get to enjoying you…”

Renbourn’s support tells its own story. A highly-technical player in his own self-articulated field of medieval folk, some of Renbourn’s best 1960s albums found him in folk/jazz after-hours conversation with another pole star for Ryley Walker: Bert Jansch. Jansch’s influence is maybe a little less pronounced on Primrose Green than it was on his superb single “The West Wind” of last year, where the influence could be read as much in Walker’s diffident delivery and his bucolic subject (mentioned: sparrows) as in his virtuosic guitar. Live performances of the tune found Walker pushing at its boundaries, finding unexpectedly noisy seams to mine within it.

As it turns out, that seems a signpost to Primrose Green, an album in which some courtly formality remains, but as a jumping-off point for more freewheeling development. The album is parenthesized by the bucolic charms of the title track and its sister, the closing “Hide In The Roses”, which ends the album on much the same note, though what takes place between them travels far and wide.

Wonderfully arranged, the album begins with Walker’s acoustic guitar joined by Danny Thompson-like double bass and snaky electric guitar. Encouraging the idea of rural retreat as analogy for lightly psychedelic away-break, Walker sings “Primrose Green, makes me high-high-high…” breaking with formal structure and launching the album’s wider trip. “Summer Dress”, with its sea-worthy gait and clavinet interventions, takes things further from terra firma, hitting on a simple lyrical idea much as Tim Buckley might, and encouraging it to give up all it can, over a rolling, jazzy funk.

The truly standout tracks on the album, like “Same Minds”, which follows, manage to hold both of these elements in position, retaining the best of both. Namely, a crisp sense of formal order, into which improvisation is poured until it looks like it might spill over the sides. “Same Minds” begins with a simple, trilling acoustic keychange, but Walker takes it much further than it ever looked likely to go. “We’ve got the same heart,” he sings, investing the line with everything he has. “We’ve got the same minds…” Like the later “Sweet Satisfaction”, (which brings John Martyn into the mix in its management of order and mounting emotional chaos), it’s spectacular, revealing the west coast of the mind the album has been hinting at: the intersection of LA Turnaround and Greetings From LA.

Walker says that parts of the album were wholly improvised, and “All Kinds Of You” late in the album seems a likely beneficiary of that policy. An electric roam through the city at night, Herbie Hancock joining the Doors, its lyric is minimal, but is delivered with such passion, it’s stretched nearly to breaking point under the weight it’s carrying. “Love Can Be Cruel”, in which John Renbourn guests on Miles Davis’s Get Up With It, is another free-radical. If the words don’t quite catch as well as you might hope, the song’s medieval science fiction gains additional texture at the close, where a J Mascis-like guitar buzz glowers over a pretty, Knights Of The Jaguar digital sequence.

Primrose Green is disorientating, casting new light on modes you thought you knew well. Wherever there are familiar elements, Walker and his excellent, jazzy, band take them to new places. “The High Road” has something of Nick Drake’s “Chime Of The City Clock” about it, with its strings and restless feel, but it seems characteristic that even when he’s on the road (“not a penny to my name…”), that romantic, metaphoric route of the questing beat or folkie, Walker wants to take things further. Rather than progressing to a chorus, the song keeps drifting on, returning only to the road, friendless, besieged by wild dogs and memories of the past.

Eventually, though, Primrose Green does come to rest, with the unadorned acoustic playing of “Hide In The Roses”, Walker taking us back to something like the simple statement which he started the album. It’s like returning home after a long journey away. Glad in some ways to be back, but irrevocably changed for the better by the experience.

Click here to watch A Short Film About Ryley Walker

Q&A

RYLEY WALKER

Tell me a bit about the writing of Primrose Green. It’s pretty open-ended, wide-roaming kind of record.

It comes from a lot of jamming. The band are heavy jazz dudes in Chicago. The songs are like riffs, we play ‘em live and we improvise. It’s all built from improvisation, it’s immediate in the songs. It came together very quickly.

Who is on the record, and how do you know them?

They’re phenomenal musicians and some of my best friends. The electric guitar player Brian Supezio is my roommate and my best friend in the world – he has a Jerry Garcia meets Django Rheinhart sort of style, it’s super-far-out but super in at the same time, you know? Ben Boye who plays the keys is one of the most brilliant musicians – he plays with Bonnie “Prince” Billy, loads of other people. Anton Hatwich plays bass, he’s like a Chicago god of stand-up bass. Frank Rosaly plays drums, a very in-demand jazz guy.

How do you fit in that world as an acoustic guitar guy?

I don’t want some wussy-ass indie rock people playing with me. I want jazz guys. Chicago’s a really collaborative town, you play folk tunes, but my friends are in the jazz scene so I’ll play with them. All my favourite records have that: Pentangle, Tim Buckley, it’s people playing with heavy-duty jazz people. Every night the tune is different. With this kind of band you can take a different path with it each time.

How did the writing work?

I had a record out last year and I had a goal of when I went out to not play any of the songs on that record, just new stuff. I would sit backstage drinking a beer and smoking a doobie and come up with something, and say, that’s a new song, let’s play that tonight. Each night it kept growing. A song is an organic thing, it needs its food and its love – if you raise that shit and if you nurture it, it keeps growing and growing. All the songs on the record are pretty much first take. The whole record we made it and mixed it in about two days.

How did that tour go?

Nobody knows me so it wasn’t like people are going, “Come on man, you didn’t play ‘Stairway’?” No-one was super pissed off or anything. For me it’s really therapeutic. I like to try new things, keep it interesting.

“Same Minds” is a great track. Did that come about the same way?

Oh totally. You know Cian Nugent? We were on tour in the states last March. He’s a classic Irish dude, like, what the fuck is he doing in the deep south. No-one’s coming to the shows, we’re bombing every night. We’re just getting hammered before the gig and nobody’s coming. He’s like “What the fock am I doing?” Every night we’d be in some shitty motel next to truckers doing speed and jam every night. That came out of us jamming in a hotel, doing nothing, just playing. I really like that song.

Your voice is more of an instrument on this record…

I’m obsessed with John Martyn and people like that. It’s really important to write words on paper, but the voice is another instrument, I want to sing the way that John Coltrane plays sax. I don’t want to sing in a monotone vein.

You used to play noise – what was your eureka moment for this kind of thing?

I played noise when I moved to Chicago when I was 17. I played fingerstyle guitar growing up and listening to Zeppelin and the Beatles and shit, I was doing the two concurrently. The noise and punk people were like, ‘you should play your song stuff live.’ A lot of my support today comes from those people and that’s where I got my chops, doing that, playing non-stop.

What’s your relationship with the greats of this period?

John Martyn, Tim Buckley, Van…they’re huge, they’re folk musicians but they reached super-far. They weren’t just playing post-war blues, they reached far into jazz and Indian music and far-put stuff. They were songwriters but pushing it super-hard. I’m moved by that passion, how they reached so far. Then in the UK people like Bert and Wizz Jones and John Martyn – those people were super-far out and into all sorts of music, super far-out.

You got a funny email from Bert’s pal John Renbourn…

I played a show with him last summer, in this festival outside Birmingham in the UK – in Nick Drake’s home town. I met him backstage and he turned out to be the coolest guy in the fucking world, “Oh yeah, how’re you doing?” He parties super-hard. I got his email and sent him my new song with a gushing email like I owe you everything man. He got back, “I was going to send you an insulting drunk email but I kind of liked it…”

Where are you headed next?

I’m already writing stuff for the next record – I think it’ll keep evolving. I think the new songs are gaining in confidence. I never want to get a goddamn job again, just concentrate on playing guitar.

INTERVIEW: JOHN ROBINSON