It’s not difficult to understand why the early death of an accomplished person bathes its victim in a halcyon haze. They are spared, if by the grimmest means possible, the senescent indignities and fearful compromises of later life, so those that admire or adore them need never fear being disappointed by them. We never had to sigh at Hank Williams opening a theme park in Branson, or John F Kennedy being disgraced by his sybaritic weaknesses, or Jimi Hendrix collaborating with Jeff Lynne. Ayrton Senna was different, in that he was regarded by fellow drivers and fans alike with quasi-mystical awe even before he died aged just 34, in an accident at 1994’s ill-starred San Marino Grand Prix. The Brazilian Formula One driver, a triple World Champion, combined a natural talent barely matched before or since with a ruthlessness that terrified and inspired. He was personally unfathomable, at once implacably calm and feverishly volatile, apparently regarding extreme speed as some species of spiritual transaction. His death on the notorious Tamburello curve was the monstrous climax of a story that the laziest matinee screenwriter wouldn’t have dared invent. The triumph of Senna is the humble recognition by its makers – ¬director Asif Kapadia, writer Manish Pandey – that their subject requires little elaboration. The film, to which Senna’s family lent their co-operation, is a straightforwardly chronological telling of Senna’s life, from his birth into considerable privilege in São Paolo to his globally mourned plunge into the barrier at Imola, rendered in home movies, archive footage – some never previously broadcast –¬ and electrifying highlights of his racing career. The input of various commentators and peers is heard, but not seen. The focus throughout remains on Senna, establishing an intimacy that renders the ending somehow shocking despite its inevitability. By the time that sickening impact plays again, Senna seems both superhuman and strangely frail. Formula One aficionados will learn much they didn’t know – and illuminating context is provided to the controversies which besmirched Senna’s record, notably his deliberate ramming of arch-rival Alain Prost to clinch the 1990 World Championship. There are also some rare snippets of Senna’s mask slipping: his reaction to being called on his characteristic on-track argy-bargy by Sir Jackie Stewart reveals a surprisingly prickly, defensive, even guilty side. But even those who regard motorsport with indifference or hostility will get plenty out of this. Great sportsmen transcend their arenas, and Senna did. Great journalism transcends its subject, and Senna does. Andrew Mueller

It’s not difficult to understand why the early death of an accomplished person bathes its victim in a halcyon haze. They are spared, if by the grimmest means possible, the senescent indignities and fearful compromises of later life, so those that admire or adore them need never fear being disappointed by them. We never had to sigh at Hank Williams opening a theme park in Branson, or John F Kennedy being disgraced by his sybaritic weaknesses, or Jimi Hendrix collaborating with Jeff Lynne.

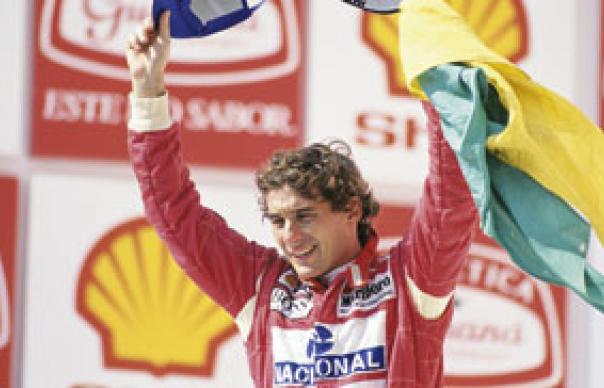

Ayrton Senna was different, in that he was regarded by fellow drivers and fans alike with quasi-mystical awe even before he died aged just 34, in an accident at 1994’s ill-starred San Marino Grand Prix. The Brazilian Formula One driver, a triple World Champion, combined a natural talent barely matched before or since with a ruthlessness that terrified and inspired. He was personally unfathomable, at once implacably calm and feverishly volatile, apparently regarding extreme speed as some species of spiritual transaction. His death on the notorious Tamburello curve was the monstrous climax of a story that the laziest matinee screenwriter wouldn’t have dared invent.

The triumph of Senna is the humble recognition by its makers – ¬director Asif Kapadia, writer Manish Pandey – that their subject requires little elaboration. The film, to which Senna’s family lent their co-operation, is a straightforwardly chronological telling of Senna’s life, from his birth into considerable privilege in São Paolo to his globally mourned plunge into the barrier at Imola, rendered in home movies, archive footage – some never previously broadcast –¬ and electrifying highlights of his racing career. The input of various commentators and peers is heard, but not seen. The focus throughout remains on Senna, establishing an intimacy that renders the ending somehow shocking despite its inevitability. By the time that sickening impact plays again, Senna seems both superhuman and strangely frail.

Formula One aficionados will learn much they didn’t know – and illuminating context is provided to the controversies which besmirched Senna’s record, notably his deliberate ramming of arch-rival Alain Prost to clinch the 1990 World Championship. There are also some rare snippets of Senna’s mask slipping: his reaction to being called on his characteristic on-track argy-bargy by Sir Jackie Stewart reveals a surprisingly prickly, defensive, even guilty side. But even those who regard motorsport with indifference or hostility will get plenty out of this. Great sportsmen transcend their arenas, and Senna did. Great journalism transcends its subject, and Senna does. Andrew Mueller