It is 1969. The summer of love’s lease has expired, but British rock is ripening into its rich and succulent autumn. Fairport Convention are hoeing into the folk tradition on Liege And Lief; Nick Drake is completing Five Leaves Left. Enter Harvest Records, set up by EMI to reap the fruits of this bumper crop, a variegated basket that includes Pink Floyd, Third Ear Band, Kevin Ayers, Deep Purple, Forest, Michael Chapman… and the folk singing sisters from Sussex, Shirley and Dolly Collins. Still only 33, by 1969 Shirley Collins had accompanied Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger from Cecil Sharp House to Young Socialist conventions in Moscow; spent a year’s epic field recording trip in the USA as folklorist Alan Lomax’s romantic and secretarial partner; and cut Folk Roots, New Routes with the high priest of the Soho folk guitar cult, Davey Graham. In 1968 she teamed up with elder sister Dolly to record The Power Of The True Love Knot, a zeitgeist-friendly folksong concoction produced by Joe Boyd and featuring The Incredible String Band. Dolly studied composition under modernist Alan Bush; by the late 60s she was living in a double decker bus in a field near Hastings, mastering the art of the flute organ, a portable keyboard dating from the 17th century. Mindful of a folk scene that had swelled from 30 nationwide clubs to over 400 in a mere five years, Harvest commissioned the sisters to record Anthems In Eden, a suite of folk tunes already premiered on John Peel’s Radio 1 show. While their hippy contemporaries imagined a hemp-smoke paradise in the Hundred Acre Wood, wrapped up in Tolkien, Celtic lore and Lewis Carroll, Shirley Collins was channelling England’s ancestral spirits in song. Anthems In Eden and Love, Death And The Lady (1970), the twin pillars of this double CD set, are built up via a curatorial selection from the motherlode of English traditional song. Side one of Anthems retitles songs like “Searching For Lambs”, “The Blacksmith” and “Our Captain Cried” as “A Meeting”, “A Denying” and “A Forsaking” to weave a patchwork “Song-Story” in which the agricultural calendar of pre-war working class life is interrupted by the Great War and converted into an unnatural cycle of birth, parting and loss. The underlying message: the Fall from Eden was an empowerment, from the ‘innocence’ of a deferent underclass that would blithely allow itself to be concripted to fight its masters’ wars, to the ‘knowledge’ of a classless modern society. We won’t get fooled again. The record’s peculiar antique grain is supplied by the young firebrand who did so much to kickstart the Early Music movement, David Munrow. In a stroke of genius, Collins and husband/producer Austin John Marshall invited Munrow’s Early Music Consort of London to the sessions, featuring future stars of the ‘authentic instruments’ movement such as Christopher Hogwood, Adam and Roderick Skeaping and Oliver Brookes, who arrived laden with crumhorns, sackbuts, rebecs, viols and harpsichord. They repeated the trick on 1970’s exceptional Love, Death And The Lady. It may begin with the time-honoured folk lines “As I walked out one morn in May”, but Collins hardly sounds full of the joys of spring. In fact, though Marshall was again producer, their marriage was on the rocks and the album’s maudlin mood is clouded with doomed love, betrayal and suicide. The arrangements – Dolly’s spiralling piano chords on “Are You Going To Leave Me”, Peter Wood’s mewling accordion on the devastating “Go From My Window”, or the military tattoos on “Salisbury Plain” courtesy of Pentangle drummer Terry Cox – are like nothing previously heard in British folk, but suspend the songs in a strangely ageless sonic timezone somewhere between Elizabethan consort music and Rubber Soul. Anthems In Eden played a decisive role in Shirley Collins’s future. Fairport Convention founder Ashley Hutchings heard the album at the end of 1969, right after quitting the band after the release of Liege And Lief. It reduced him to a fit of body-wracking sobs, and within less than a year, he had sought out and married its creator, sweeping away most of the dead leaves lingering after Love, Death And The Lady. No Roses, recorded in 1971 by the couple’s newly formed Albion Country Band, brilliantly grafted Fairport-style electric pastoralia onto Collins’s murderous balladry. That record was not part of the Harvest story, but this set does include Amaranth, the extra six tracks the group laid down for the 1976 edition of Anthems In Eden, plus another couple of merry tunes unreleased from the same period. Her marriage did not survive long after this high summer, and she only made one further album before effacing herself from public performance. But Harvest’s vintage crop of progressive folk survives as the pinnacle of her achievements. ROB YOUNG UNCUT Q&A: Shirley Collins Uncut: How do you think your music chimed with Harvest’s hippy audience? Shirley Collins: Dolly (Who died in 1995) and I were so far removed from popular music that’s it’s quite miraculous that it all happened. I was never a hippy – couldn’t stand all that vague twee floatiness or the smell of patchouli! My England was Daniel Defoe, Robert Herrick, Hogarth, John Clare, Blake, with a touch of Henry Fielding for larks! My songs, coming from a long and genuine tradition, carried with them a truthful, clear vision of the past, of real lives, and I felt that, because of my background, I was a conduit between then and now. What was your working relationship like with your husband as producer? Austin John Marshall was a clever, inventive, maddening man. Yes, our marriage was breaking down at the time we were recording Love, Death And The Lady. But John had a clear vision for both albums, and the drive to see it through. And I’m glad he persuaded me to add Terry Cox’s percussion to “The Plains Of Waterloo” – it still gives me goosebumps! What did the idea of 'Eden' mean to you in 1969? Being a child throughout World War Two, surviving it, feeling optimistic, loving the English countryside and feeling proud and glad to be English – I suppose England was my Eden. And yet I don’t feel I saw it through rose-tinted spectacles. Growing up in a working class family made me aware of the hardships that people endured and overcame. I felt a great connection to those rural labouring classes who’d sung the songs before me. I was fascinated by the past, so I was always aware of the dark heart of English history. INTERVIEW: ROB YOUNG

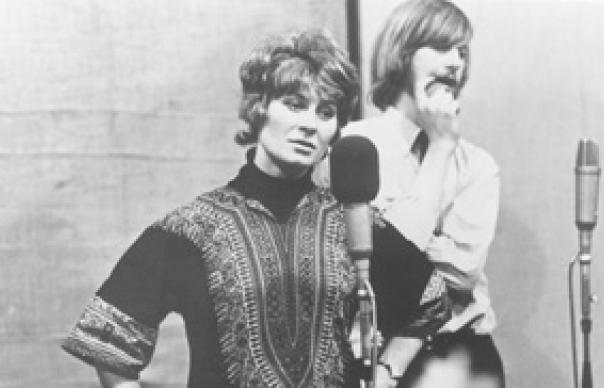

It is 1969. The summer of love’s lease has expired, but British rock is ripening into its rich and succulent autumn. Fairport Convention are hoeing into the folk tradition on Liege And Lief; Nick Drake is completing Five Leaves Left. Enter Harvest Records, set up by EMI to reap the fruits of this bumper crop, a variegated basket that includes Pink Floyd, Third Ear Band, Kevin Ayers, Deep Purple, Forest, Michael Chapman… and the folk singing sisters from Sussex, Shirley and Dolly Collins.

Still only 33, by 1969 Shirley Collins had accompanied Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger from Cecil Sharp House to Young Socialist conventions in Moscow; spent a year’s epic field recording trip in the USA as folklorist Alan Lomax’s romantic and secretarial partner; and cut Folk Roots, New Routes with the high priest of the Soho folk guitar cult, Davey Graham.

In 1968 she teamed up with elder sister Dolly to record The Power Of The True Love Knot, a zeitgeist-friendly folksong concoction produced by Joe Boyd and featuring The Incredible String Band. Dolly studied composition under modernist Alan Bush; by the late 60s she was living in a double decker bus in a field near Hastings, mastering the art of the flute organ, a portable keyboard dating from the 17th century. Mindful of a folk scene that had swelled from 30 nationwide clubs to over 400 in a mere five years, Harvest commissioned the sisters to record Anthems In Eden, a suite of folk tunes already premiered on John Peel’s Radio 1 show.

While their hippy contemporaries imagined a hemp-smoke paradise in the Hundred Acre Wood, wrapped up in Tolkien, Celtic lore and Lewis Carroll, Shirley Collins was channelling England’s ancestral spirits in song. Anthems In Eden and Love, Death And The Lady (1970), the twin pillars of this double CD set, are built up via a curatorial selection from the motherlode of English traditional song. Side one of Anthems retitles songs like “Searching For Lambs”, “The Blacksmith” and “Our Captain Cried” as “A Meeting”, “A Denying” and “A Forsaking” to weave a patchwork “Song-Story” in which the agricultural calendar of pre-war working class life is interrupted by the Great War and converted into an unnatural cycle of birth, parting and loss. The underlying message: the Fall from Eden was an empowerment, from the ‘innocence’ of a deferent underclass that would blithely allow itself to be concripted to fight its masters’ wars, to the ‘knowledge’ of a classless modern society. We won’t get fooled again.

The record’s peculiar antique grain is supplied by the young firebrand who did so much to kickstart the Early Music movement, David Munrow. In a stroke of genius, Collins and husband/producer Austin John Marshall invited Munrow’s Early Music Consort of London to the sessions, featuring future stars of the ‘authentic instruments’ movement such as Christopher Hogwood, Adam and Roderick Skeaping and Oliver Brookes, who arrived laden with crumhorns, sackbuts, rebecs, viols and harpsichord. They repeated the trick on 1970’s exceptional Love, Death And The Lady. It may begin with the time-honoured folk lines “As I walked out one morn in May”, but Collins hardly sounds full of the joys of spring.

In fact, though Marshall was again producer, their marriage was on the rocks and the album’s maudlin mood is clouded with doomed love, betrayal and suicide. The arrangements – Dolly’s spiralling piano chords on “Are You Going To Leave Me”, Peter Wood’s mewling accordion on the devastating “Go From My Window”, or the military tattoos on “Salisbury Plain” courtesy of Pentangle drummer Terry Cox – are like nothing previously heard in British folk, but suspend the songs in a strangely ageless sonic timezone somewhere between Elizabethan consort music and Rubber Soul.

Anthems In Eden played a decisive role in Shirley Collins’s future. Fairport Convention founder Ashley Hutchings heard the album at the end of 1969, right after quitting the band after the release of Liege And Lief. It reduced him to a fit of body-wracking sobs, and within less than a year, he had sought out and married its creator, sweeping away most of the dead leaves lingering after Love, Death And The Lady. No Roses, recorded in 1971 by the couple’s newly formed Albion Country Band, brilliantly grafted Fairport-style electric pastoralia onto Collins’s murderous balladry. That record was not part of the Harvest story, but this set does include Amaranth, the extra six tracks the group laid down for the 1976 edition of Anthems In Eden, plus another couple of merry tunes unreleased from the same period. Her marriage did not survive long after this high summer, and she only made one further album before effacing herself from public performance. But Harvest’s vintage crop of progressive folk survives as the pinnacle of her achievements.

ROB YOUNG

UNCUT Q&A: Shirley Collins

Uncut: How do you think your music chimed with Harvest’s hippy audience?

Shirley Collins: Dolly (Who died in 1995) and I were so far removed from popular music that’s it’s quite miraculous that it all happened. I was never a hippy – couldn’t stand all that vague twee floatiness or the smell of patchouli! My England was Daniel Defoe, Robert Herrick, Hogarth, John Clare, Blake, with a touch of Henry Fielding for larks! My songs, coming from a long and genuine tradition, carried with them a truthful, clear vision of the past, of real lives, and I felt that, because of my background, I was a conduit between then and now.

What was your working relationship like with your husband as producer?

Austin John Marshall was a clever, inventive, maddening man. Yes, our marriage was breaking down at the time we were recording Love, Death And The Lady. But John had a clear vision for both albums, and the drive to see it through. And I’m glad he persuaded me to add Terry Cox’s percussion to “The Plains Of Waterloo” – it still gives me goosebumps!

What did the idea of ‘Eden’ mean to you in 1969?

Being a child throughout World War Two, surviving it, feeling optimistic, loving the English countryside and feeling proud and glad to be English – I suppose England was my Eden. And yet I don’t feel I saw it through rose-tinted spectacles. Growing up in a working class family made me aware of the hardships that people endured and overcame. I felt a great connection to those rural labouring classes who’d sung the songs before me. I was fascinated by the past, so I was always aware of the dark heart of English history.

INTERVIEW: ROB YOUNG