Post-rock's crowning glory beautifully remastered, with bonus tracks, a film... and its mystery intact... Come the 1990s, amongst a certain constituency of alternative musicians, there was the increasing feeling that rock music was played out. Post rock, a term coined in Melody Maker by Simon Reynolds, was used to describe a variety of diverse bands pushing at the edges of traditional rock form. In the UK, groups like Stereolab and Pram were reintegrating the lessons learned in electronic and Krautrock. In Chicago, Tortoise, The Sea And Cake and Gastr Del Sol were experimenting with dub production techniques, or drawing on the city’s experimental jazz traditions. Before all of this, though, there was a band of teenage punk kids from Louisville, Kentucky. They were named after drummer Britt Walford’s goldfish, and they were called Slint. Slint, who existed between the years of 1986 and 1992, made two records. The first, the Steve Albini-produced Tweez, was released in 1989 on the local Kentucky label Jennifer Hartman. But it’s the second, Spiderland, that they’re remembered for. Six tracks of nocturnal guitar wanderings slowly twine around hushed, evocative tales of fairground fortune tellers, vampire princes and bloody shipwrecks. By the time it was released on Touch And Go in 1992, the band had already broken up, and rumours persisted some, or all, had checked themselves into a psychiatric hospital. The band’s strangely abrupt end, coupled with a relative shortage of evidence testifying to their existence, meant that Spiderland took on the quality of urban myth: an eerie mystery passed on like whispers in the schoolyard, of something awful that happened to some young men in the town just down the way. Afterwards, the participants moved onto other bands: Walford (as “Mike Hunt”) drummed on The Breeders’ Pod; co-vocalist/guitarist Brian McMahan founded The For Carnation; guitarist David Pajo has pursued a fruitful solo career and played in groups including Tortoise, Interpol and Yeah Yeah Yeahs; and all, including bassist Todd Brashear, have played with their childhood friend Will Oldham. When trying to put your finger on the essence of Slint, you’re still drawn back to Spiderland’s cover: a black-and-white shot of the four fresh-faced participants floating in a quarry, part submerged, as if about to sink into the inky depths. Slint reformed in 2005 at the behest of Barry Hogan of concert promoters All Tomorrow’s Parties, and have found a second life recreating Spiderland live, in crystal clarity, without ever stepping near a recording studio. They have, however, worked up this: a lavish triple-vinyl box set that collects the album, affectionately remastered by Shellac’s Bob Weston, with demos, outtakes and practice tapes, plus a booklet of photos and ephemera and Breadcrumb Trail, a 90 minute documentary by filmmaker Lance Bangs. The remastered Spiderland material aside, it is the documentary itself that is the most remarkable part of this box: a fastidiously researched piece that blows away the smoke but somehow leaves the mystique intact. There are childhood photos, extensive interviews with band members and fellow travellers (Steve Albini, James Murphy, friends and former bandmates such as Sean "Rat" Garrison of pre-Slint outfit Maurice and Jon Cook of Rodan), live footage from a Louisville Battle Of The Bands, and most unbelievably, VHS recordings of the band jamming away in the Walford family basement, mere slips of lads crouched on the lino, already playing this strange, uncanny music note-perfect. There is fascinating trivia – look close at the cover of Tweez, that’s Will Oldham in the front seat wearing a crash helmet. And there is vivid sense of the intensity of the group’s partnership, particularly between Walford, mischievous and uninhibited, and McMahan, bookish and intense. Ian Mackaye of Fugazi, who hung out with Slint during a stay in Louisville, has a neat summation: “People from Louisville, they’re just fucking crazy… they’re insane.” For all that Slint have been an influence on groups such as Shellac and Mogwai, it is pleasing to note that Spiderland has only got richer with age. In large part, this is thanks to their preternatural technicality. Pajo is already a hugely skilled guitarist, his style still steeped in hardcore, but radically pared down in a manner suggesting the influence of American Primitive guitarists like John Fahey, and employing all manner of curious tunings and fretboard tricks. Opener “Breadcrumb Trail” floats by like a lucid dream, queer twinkling harmonics shadowing McMahan as he drifts around a rickety fairground, befriending a fortune teller and taking a trip on a rollercoaster that commences a lurch of squealing riffs and roaring distortion. Walford, meanwhile, is the engine of the band, behind the unsettling 5/4 chug of “Nosferatu Man”, and taking up guitar for the spare, skeletal “Don, Aman”, the tale of a weird drifter that cuts off just before its moment of dramatic realisation. McMahan, meanwhile, is the knot in Spiderland’s stomach, trying to put words to the fearful sensations conjured into being by these cryptic guitar tangles. On the slow downward spiral of “Washer”, he sings in a thin tremble, first threatening to leave, then begging his lover not to go, and declaring: “Every time I ever cried from fear/Was just a mistake that I made”. The climactic “Good Morning Captain”, loosely based on Coleridge’s The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner, offers an emotional climax is one of the most wrenching in all indie rock: “I’m sorry… I miss you,” mutters McMahan, and as guitars rise to a clamour he repeats the words at a bellow. In Breadcrumb Trail, Walford recalls McMahan returned to the control room having thrown up on himself. Completing the Spiderland box is a collection of outtakes, offcuts and demos, much of which confirms just how great Spiderland sounded, how diminished it would have been sans vocals. Essential, though, is “Pam”, a brooding instrumental headbanger, presumably excised for reasons of mood and pacing (it also appears as a vocal demo with some somewhat daft lyrics); a take on “Glenn”, slightly slower and more pensive than the version that made it onto their posthumous 1994 EP; and a fairly reverent live take on Neil Young’s “Cortez The Killer” recorded in Chicago in 1989 that neatly approximates the original’s craggy endurance. Intriguing but frustrating, meanwhile, is a pair of demos, titled “Todd’s Song” and “Brian’s Song”. The former is a comparatively evolved, yet still unfinished instrumental that strikes a slightly lighter note than Spiderland; the latter, an arcane guitar scrawl to primitive boom-clack drum machine pointing ahead to McMahan’s work with The For Carnation. Both are a reminder that Slint have work unfinished. Yet nine years since their reformation, they remain a zombie band, recreating past glories but collectively unwilling – or unable – to step back into the land of the living. This is a remarkable document of a remarkable band. Is it churlish to ask for more? Louis Pattison

Post-rock’s crowning glory beautifully remastered, with bonus tracks, a film… and its mystery intact…

Come the 1990s, amongst a certain constituency of alternative musicians, there was the increasing feeling that rock music was played out. Post rock, a term coined in Melody Maker by Simon Reynolds, was used to describe a variety of diverse bands pushing at the edges of traditional rock form. In the UK, groups like Stereolab and Pram were reintegrating the lessons learned in electronic and Krautrock. In Chicago, Tortoise, The Sea And Cake and Gastr Del Sol were experimenting with dub production techniques, or drawing on the city’s experimental jazz traditions. Before all of this, though, there was a band of teenage punk kids from Louisville, Kentucky. They were named after drummer Britt Walford’s goldfish, and they were called Slint.

Slint, who existed between the years of 1986 and 1992, made two records. The first, the Steve Albini-produced Tweez, was released in 1989 on the local Kentucky label Jennifer Hartman. But it’s the second, Spiderland, that they’re remembered for. Six tracks of nocturnal guitar wanderings slowly twine around hushed, evocative tales of fairground fortune tellers, vampire princes and bloody shipwrecks.

By the time it was released on Touch And Go in 1992, the band had already broken up, and rumours persisted some, or all, had checked themselves into a psychiatric hospital. The band’s strangely abrupt end, coupled with a relative shortage of evidence testifying to their existence, meant that Spiderland took on the quality of urban myth: an eerie mystery passed on like whispers in the schoolyard, of something awful that happened to some young men in the town just down the way.

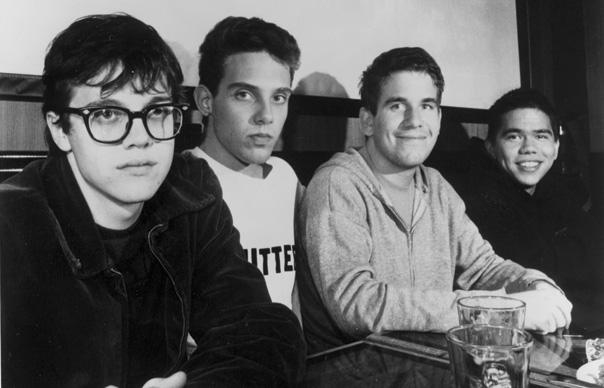

Afterwards, the participants moved onto other bands: Walford (as “Mike Hunt”) drummed on The Breeders’ Pod; co-vocalist/guitarist Brian McMahan founded The For Carnation; guitarist David Pajo has pursued a fruitful solo career and played in groups including Tortoise, Interpol and Yeah Yeah Yeahs; and all, including bassist Todd Brashear, have played with their childhood friend Will Oldham. When trying to put your finger on the essence of Slint, you’re still drawn back to Spiderland’s cover: a black-and-white shot of the four fresh-faced participants floating in a quarry, part submerged, as if about to sink into the inky depths.

Slint reformed in 2005 at the behest of Barry Hogan of concert promoters All Tomorrow’s Parties, and have found a second life recreating Spiderland live, in crystal clarity, without ever stepping near a recording studio. They have, however, worked up this: a lavish triple-vinyl box set that collects the album, affectionately remastered by Shellac’s Bob Weston, with demos, outtakes and practice tapes, plus a booklet of photos and ephemera and Breadcrumb Trail, a 90 minute documentary by filmmaker Lance Bangs.

The remastered Spiderland material aside, it is the documentary itself that is the most remarkable part of this box: a fastidiously researched piece that blows away the smoke but somehow leaves the mystique intact. There are childhood photos, extensive interviews with band members and fellow travellers (Steve Albini, James Murphy, friends and former bandmates such as Sean “Rat” Garrison of pre-Slint outfit Maurice and Jon Cook of Rodan), live footage from a Louisville Battle Of The Bands, and most unbelievably, VHS recordings of the band jamming away in the Walford family basement, mere slips of lads crouched on the lino, already playing this strange, uncanny music note-perfect.

There is fascinating trivia – look close at the cover of Tweez, that’s Will Oldham in the front seat wearing a crash helmet. And there is vivid sense of the intensity of the group’s partnership, particularly between Walford, mischievous and uninhibited, and McMahan, bookish and intense. Ian Mackaye of Fugazi, who hung out with Slint during a stay in Louisville, has a neat summation: “People from Louisville, they’re just fucking crazy… they’re insane.”

For all that Slint have been an influence on groups such as Shellac and Mogwai, it is pleasing to note that Spiderland has only got richer with age. In large part, this is thanks to their preternatural technicality. Pajo is already a hugely skilled guitarist, his style still steeped in hardcore, but radically pared down in a manner suggesting the influence of American Primitive guitarists like John Fahey, and employing all manner of curious tunings and fretboard tricks. Opener “Breadcrumb Trail” floats by like a lucid dream, queer twinkling harmonics shadowing McMahan as he drifts around a rickety fairground, befriending a fortune teller and taking a trip on a rollercoaster that commences a lurch of squealing riffs and roaring distortion. Walford, meanwhile, is the engine of the band, behind the unsettling 5/4 chug of “Nosferatu Man”, and taking up guitar for the spare, skeletal “Don, Aman”, the tale of a weird drifter that cuts off just before its moment of dramatic realisation.

McMahan, meanwhile, is the knot in Spiderland’s stomach, trying to put words to the fearful sensations conjured into being by these cryptic guitar tangles. On the slow downward spiral of “Washer”, he sings in a thin tremble, first threatening to leave, then begging his lover not to go, and declaring: “Every time I ever cried from fear/Was just a mistake that I made”. The climactic “Good Morning Captain”, loosely based on Coleridge’s The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner, offers an emotional climax is one of the most wrenching in all indie rock: “I’m sorry… I miss you,” mutters McMahan, and as guitars rise to a clamour he repeats the words at a bellow. In Breadcrumb Trail, Walford recalls McMahan returned to the control room having thrown up on himself.

Completing the Spiderland box is a collection of outtakes, offcuts and demos, much of which confirms just how great Spiderland sounded, how diminished it would have been sans vocals. Essential, though, is “Pam”, a brooding instrumental headbanger, presumably excised for reasons of mood and pacing (it also appears as a vocal demo with some somewhat daft lyrics); a take on “Glenn”, slightly slower and more pensive than the version that made it onto their posthumous 1994 EP; and a fairly reverent live take on Neil Young’s “Cortez The Killer” recorded in Chicago in 1989 that neatly approximates the original’s craggy endurance.

Intriguing but frustrating, meanwhile, is a pair of demos, titled “Todd’s Song” and “Brian’s Song”. The former is a comparatively evolved, yet still unfinished instrumental that strikes a slightly lighter note than Spiderland; the latter, an arcane guitar scrawl to primitive boom-clack drum machine pointing ahead to McMahan’s work with The For Carnation. Both are a reminder that Slint have work unfinished. Yet nine years since their reformation, they remain a zombie band, recreating past glories but collectively unwilling – or unable – to step back into the land of the living. This is a remarkable document of a remarkable band. Is it churlish to ask for more?

Louis Pattison