Slithery guitar from the Fahey school, with added architecture... Over the last 15 years, Steve Gunn has established a reputation as a fine guitarist in the vein of American primitives such as John Fahey, exploring folk stylings with an added dusting of jazz, minimalism and raga. Google, and you’ll probably find him listed as a player in Kurt Vile’s band. Go deeper, and he’ll be referenced as an improvisational, blues-based player. The word “deconstruction” may appear, which is always worrying. Gunn, it’s true, is an exploratory guitarist. His style is restless, even when it is soothing (it is often soothing). It is dynamic, even when it is walking in circles, and many of his tunes are Olympian in their pursuit of circularity. “Trailways Ramble”, for instance, orbits relentlessly, with only slight variation, until the entrance of a scratchy cello after three minutes. “Water Wheel”, as you’d expect, keeps on turning. Repetition? He digs repetition. At his best, Gunn is understated, an attitude which could also be applied to his career. Many of his records have been (very) limited editions of 500 or less. His 2009 album, Too Early For The Hammer was restricted to 378 copies. The LP pressing of 2009’s Boerum Palace was capped at 823 copies (through Three Lobed Records have just thrown caution to the breeze and re-pressed another 500 on purple vinyl). His recent Record Store Day collaboration with Hiss Golden Messenger (as Golden Gunn) ran to an extravagant 995 copies, and is recommended as a playful entry point to the music of both Gunn and HGM, though it doesn’t sound quite like either. But Time Off does mark a progression of sorts. It shows that Gunn has recalibrated slightly, focusing his energies on songcraft, where previously he appeared to be more interested in improvisation, and continually fanning the creative spark. He is also exploring the dynamics of a group, though his regular collaborators, drummer John Truscinski and bassist Justin Tripp, know enough to leave the guitar audible. Gunn lists Phil Spector as an influence, but don’t expect lacquered harmonies and a wall of sound. The Philadelphia-raised, New York-based guitarist’s trademarks are precision and restraint. He doesn’t do riffs, exactly. He has a balmy, effortless voice, and his tunes unfurl like bales of wire rolling down country roads. JJ Cale is an obvious comparison, as is the atmosphere of Bert Jansch’s (slightly) countrified 1974 album LA Turnaround. Michael Chapman’s first three albums are an acknowledged inspiration. Maybe there is a hint of John Cale’s corner of the Velvet Underground in the seasoning of a song such as “Old Strange”, but the vocals are closer to one of Paul Weller’s more bucolic moments. The song itself is a rumination on death, and a tribute to Jack Rose, the late Pelt guitarist, whose solo work blazed a similarly eclectic trail. (Gunn recorded the song previously with the Black Twig Pickers, and it’s interesting to compare the two versions. With the Twigs, the song was thick with smoke of a hillbilly campfire; here, it’s mournful and pained.) And then there is “Lurker”. Previously released as “The Lurker Extended<.strong>” on a whole side of Not the Spaces You Know, Three Lobed’s 10th anniversary box set (2011), it was a gorgeous, meandering tune, all wire and sunlight, dedicated to the “street lurkers” of Brooklyn’s Boerum Hill. Here, it’s trimmed to a mere eight minutes of graceful slitheriness from the Fahey school. At first, the mathematical precision of the song seems to work against it; even the production seems to favour the geometry of the tune, rather than the soulful guitar, which is buried somewhere in the left channel. But after a time, it starts to click. And click. And click. Yes, Time Off is a technical record. Generically, it’s improbable: progressive folk, with psychedelic swirls, delivered with so much confidence that it sounds like dispassion. At times, it’s like an architectural drawing. But the repetitions soothe and tease, and then you start to hear the leaves. Alastair McKay Q&A How was it playing with Kurt Vile? Kurt and I come from the same small town, a suburb outside of Philadelphia. I’ve been a fan of his music and we have a lot of mutual friends. He heard Time Off and extended the invitation of me being the opener for his first gigs supporting his new album. We hit it off and he asked me if I wanted to sit in with his band. Of course I was up for that. What was the idea for the album? It’s a culmination of everything I’ve been gathering over the past ten years or so. It’s pulling from all directions. I’ve been concentrating on songwriting, but the musicians are old friends and have played with me in different projects. It all came together when I presented these songs. The other stuff I do - instrumental guitar work and avant garde improvisational stuff - all of that had its role. Is there a different aesthetic from your earlier work? The album I made before was more a solo bedroom-style album. I wanted to get away from that and flesh the songs out, but not in a rock or indie rock way. Not many people are attempting that these days. The three of us in this band are appreciators and record collectors. We wanted to make an album we would want to listen to. INTERVIEW: ALASTAIR McKAY

Slithery guitar from the Fahey school, with added architecture…

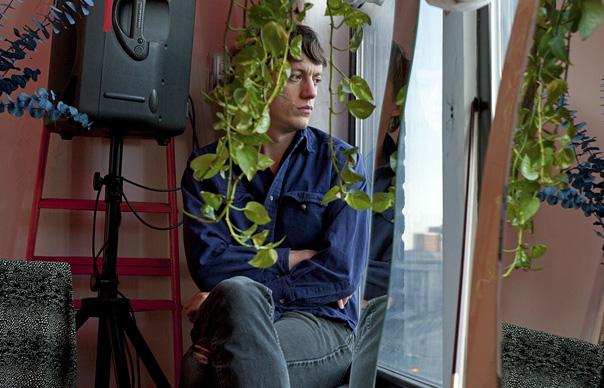

Over the last 15 years, Steve Gunn has established a reputation as a fine guitarist in the vein of American primitives such as John Fahey, exploring folk stylings with an added dusting of jazz, minimalism and raga. Google, and you’ll probably find him listed as a player in Kurt Vile’s band. Go deeper, and he’ll be referenced as an improvisational, blues-based player. The word “deconstruction” may appear, which is always worrying.

Gunn, it’s true, is an exploratory guitarist. His style is restless, even when it is soothing (it is often soothing). It is dynamic, even when it is walking in circles, and many of his tunes are Olympian in their pursuit of circularity. “Trailways Ramble”, for instance, orbits relentlessly, with only slight variation, until the entrance of a scratchy cello after three minutes. “Water Wheel”, as you’d expect, keeps on turning. Repetition? He digs repetition.

At his best, Gunn is understated, an attitude which could also be applied to his career. Many of his records have been (very) limited editions of 500 or less. His 2009 album, Too Early For The Hammer was restricted to 378 copies. The LP pressing of 2009’s Boerum Palace was capped at 823 copies (through Three Lobed Records have just thrown caution to the breeze and re-pressed another 500 on purple vinyl). His recent Record Store Day collaboration with Hiss Golden Messenger (as Golden Gunn) ran to an extravagant 995 copies, and is recommended as a playful entry point to the music of both Gunn and HGM, though it doesn’t sound quite like either.

But Time Off does mark a progression of sorts. It shows that Gunn has recalibrated slightly, focusing his energies on songcraft, where previously he appeared to be more interested in improvisation, and continually fanning the creative spark. He is also exploring the dynamics of a group, though his regular collaborators, drummer John Truscinski and bassist Justin Tripp, know enough to leave the guitar audible.

Gunn lists Phil Spector as an influence, but don’t expect lacquered harmonies and a wall of sound. The Philadelphia-raised, New York-based guitarist’s trademarks are precision and restraint. He doesn’t do riffs, exactly. He has a balmy, effortless voice, and his tunes unfurl like bales of wire rolling down country roads.

JJ Cale is an obvious comparison, as is the atmosphere of Bert Jansch’s (slightly) countrified 1974 album LA Turnaround. Michael Chapman’s first three albums are an acknowledged inspiration. Maybe there is a hint of John Cale’s corner of the Velvet Underground in the seasoning of a song such as “Old Strange”, but the vocals are closer to one of Paul Weller’s more bucolic moments. The song itself is a rumination on death, and a tribute to Jack Rose, the late Pelt guitarist, whose solo work blazed a similarly eclectic trail. (Gunn recorded the song previously with the Black Twig Pickers, and it’s interesting to compare the two versions. With the Twigs, the song was thick with smoke of a hillbilly campfire; here, it’s mournful and pained.)

And then there is “Lurker”. Previously released as “The Lurker Extended<.strong>” on a whole side of Not the Spaces You Know, Three Lobed’s 10th anniversary box set (2011), it was a gorgeous, meandering tune, all wire and sunlight, dedicated to the “street lurkers” of Brooklyn’s Boerum Hill. Here, it’s trimmed to a mere eight minutes of graceful slitheriness from the Fahey school. At first, the mathematical precision of the song seems to work against it; even the production seems to favour the geometry of the tune, rather than the soulful guitar, which is buried somewhere in the left channel. But after a time, it starts to click. And click. And click.

Yes, Time Off is a technical record. Generically, it’s improbable: progressive folk, with psychedelic swirls, delivered with so much confidence that it sounds like dispassion. At times, it’s like an architectural drawing. But the repetitions soothe and tease, and then you start to hear the leaves.

Alastair McKay

Q&A

How was it playing with Kurt Vile?

Kurt and I come from the same small town, a suburb outside of Philadelphia. I’ve been a fan of his music and we have a lot of mutual friends. He heard Time Off and extended the invitation of me being the opener for his first gigs supporting his new album. We hit it off and he asked me if I wanted to sit in with his band. Of course I was up for that.

What was the idea for the album?

It’s a culmination of everything I’ve been gathering over the past ten years or so. It’s pulling from all directions. I’ve been concentrating on songwriting, but the musicians are old friends and have played with me in different projects. It all came together when I presented these songs. The other stuff I do – instrumental guitar work and avant garde improvisational stuff – all of that had its role.

Is there a different aesthetic from your earlier work?

The album I made before was more a solo bedroom-style album. I wanted to get away from that and flesh the songs out, but not in a rock or indie rock way. Not many people are attempting that these days. The three of us in this band are appreciators and record collectors. We wanted to make an album we would want to listen to.

INTERVIEW: ALASTAIR McKAY