When Melody Maker’s Roy Hollingworth broke the news to his readers in 1970 that Taste, the popular Irish trio, were disbanding, his tone was one of shock. “After one of the most ludicrous of upsets... You couldn’t really believe what was actually going on.” Many of the 600,000 attendees of t...

When Melody Maker’s Roy Hollingworth broke the news to his readers in 1970 that Taste, the popular Irish trio, were disbanding, his tone was one of shock. “After one of the most ludicrous of upsets… You couldn’t really believe what was actually going on.” Many of the 600,000 attendees of the Isle of Wight Festival, held six weeks earlier, would have agreed with him. Fronted by guitarist and singer Rory Gallagher, Taste had stormed the festival’s Friday evening slot and seemed poised for a breakthrough, not a break-up.

What was it about Taste that could ignite the Isle of Wight yet end in a bitter, inexplicable divorce? Why did Gallagher never play their songs in public again? There are no easy answers on I’ll Remember, a Taste live-and-studio boxset that follows the recent Gallagher anthologies Kickback City, Live At Montreux and Irish Tour ’74. Over four discs (1967-70), we hear a blues-rock band stretching out onstage – and showing off their folk and jazz influences in the studio – but the one thing we never get is a sense of climax or closure. Are Taste one of rock’s great what-might-have-beens? If so, Gallagher’s solo career (1971-95) had to serve as their alternative history.

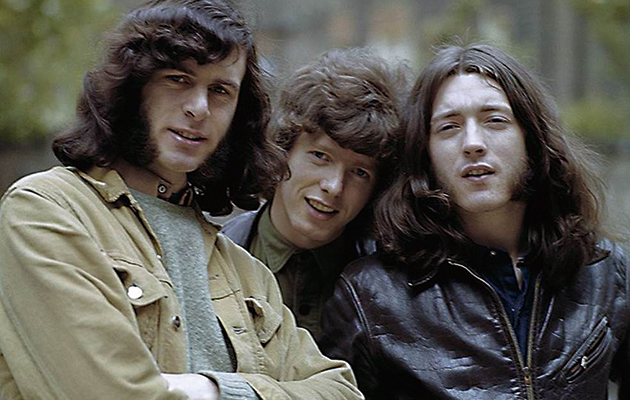

Gallagher emerged from the Irish showbands of the mid-’60s as a teenage prodigy and blues fanatic. He formed Taste with two Cork musicians, Eric Kitteringham (bass) and Norman D’Amery (drums), soon descending on Belfast, 200 miles to the north, where the Maritime Hotel still reverberated from the excitement of seeing Van Morrison and Them in 1964. On a demo recorded at the Maritime to attract the interest of Decca in London, Taste sound like a beat combo with blues leanings; there are times when Gallagher’s harmonica is as prominent as his guitar. But an instrumental, “Norman Invasion”, suggests he may be paying close attention to Jimi Hendrix. And be thinking, perhaps, that Taste should become more of a power trio.

They start to record. A 1968 single, “Blister On The Moon”, with its strange lyrics about a totalitarian society crushing a little man who dares to fight back, is backed by the equally striking “Born On The Wrong Side Of Time”, which crams the entire repertoire of the Yardbirds into three minutes and 20 seconds. Captured live at the Woburn Music Festival that summer, Taste are loose and fiery, like Ten Years After channelling the MC5. Hendrix, who topped the Woburn bill the night before, would surely have been impressed by the way Taste tear it up on their 11-minute closing medley, which includes “Baby Please Don’t Go” and “You Shook Me”.

A new rhythm section – Richard McCracken (bass) and John Wilson (drums) – was installed before Taste made their self-titled Polydor debut album in the autumn of ’68. Released the following April, it showcases Gallagher the way Led Zeppelin, in January, had showcased Jimmy Page: as a bluesman, a folkie, a multi-faceted whizzkid, a maestro. Some of the soloing on Taste is delicious. “Hail”, an acoustic blues, is dazzlingly accomplished for a 20-year-old. And his effortless slide playing on Lead Belly’s “Leaving Blues” is the sort of thing the Stones had to hire Ry Cooder to do for them. No wonder Gallagher was later considered as a replacement for Mick Taylor.

McCracken and Wilson don’t stand out on the debut LP, but they’re more of a force on the follow-up. On The Boards (1970) shows Taste exploring and advancing. Wilson was a fan of Tony Williams’ Lifetime. Gallagher, studying his Eric Dolphy records, taught himself to play an alto saxophone in a matter of weeks. On The Boards is progressive, recalling Family here and there, but Gallagher’s smoky alto solo on the title track, with Wilson on rimshots and ride cymbal, is something different entirely – like John Densmore getting together with the Don Rendell-Ian Carr quintet and not worrying about any boundaries. Taste had come a long way in 12 months. “I’ll Remember”, which gives the boxset its title, is typically schizophrenic, one minute a brooding rock song, the next a jazzy swing tune.

The 1970 Isle of Wight appearance is omitted from the four discs, alas (though a DVD/CD release of it is planned), but I’ll Remember features two live performances from the same year. One is a recording for Radio 1’s In Concert, which suffers from muffled mono sound and too much hiss. Much better (and in stereo) is a 50-minute chunk of Taste in Stockholm, on their final European tour, where they play with remarkable intensity for three men who are barely speaking. Gallagher, encouraged by Taste’s manager to regard the rhythm section as dispensable sidemen, had quickly become convinced that he could succeed without them. He irritated Wilson and McCracken by launching into solo blues numbers onstage, often several at a time, giving them nothing to do. Wilson disliked encores. Gallagher wanted to play ten a night. They argued over missing money, each suspecting the other. It later transpired that the manager was the one with the Polydor deal, not them. If he hadn’t been so fond of the music biz practices of the ’60s, he could have had one of the major bands of the ’70s.

Prior to Gallagher’s death in 1995, a reconciliation took place of the classic Taste lineup, and there was even talk of them playing a peace concert for Northern Ireland. But it didn’t happen, and resentment over old contracts continued to linger. Bassist McCracken lives in London now, working for the company that owns Wembley Stadium. He avoids interviews about Taste and, according to Wilson, seldom discusses the band in private. Wilson himself formed a trio in 2000 to play material from the Taste era, incensing Gallagher’s fans (and brother-manager Donal) by calling the new band Taste. After throat cancer surgery two years ago, however, Wilson was advised by doctors to avoid strenuous activity and sold his drumkit. Listening to Taste on I’ll Remember as young musicians with their lives ahead of them, it’s poignant to think that none of them plays music any more.

Q&A

JOHN WILSON (Taste drummer, 1968-70)

What are your feelings about Taste now?

Most people who refer to Taste are talking about Rory. They see it as one facet of Rory’s career. My main feeling about Taste is that I was privileged to play with Rory – and Richard – at a time when bands were allowed to be at their most expressive. There was no pressure on Rory or any of us. We were just three guys who went onstage every night and had fun.

Taste are often called a blues band, but you were more flexible than that. Rock, folk, jazz…

We put no labels on anything. To quote the phrase from Star Trek, it’s the blues, Jim, but not as we know it. Coming from Ireland in that era, we all had lots of influences. The showbands played everything from trad jazz to rock’n’roll. I came from brass bands, playing cornet and euphonium. Rory liked country music, a lot of jazz stuff. We just experimented and tried incorporating things into our songs to see if they worked. There was no format, no setlist, nothing like that.

The boxset has some alternate takes from the two studio albums. Would you record, say, three or four takes of each song?

Some of them may have been one take. Those studio dates were very quick. Straight in and straight out, not a lot of thought going into it. I would have preferred releasing live albums. The studio stuff seemed a bit false, in a way, compared to what we were giving the punters every night.

Was there anything that could have kept Taste together?

Yes. Better management. We were good friends who loved playing music, but unfortunately no-one was getting any financial reward other than our manager. And by a method of divide-and-conquer, he split the band. I tried to give him the benefit of the doubt. It was only afterwards that I realised how bad he was.

DONAL GALLAGHER (Taste road manager, brother of Rory)

The first Taste album has Rory’s face on the cover and seems like a vehicle for his talent as a guitarist. Did Polydor instantly single him out as the star of the band?

What had occurred with Taste Mark I was that they’d got a residency at the Marquee and Polydor had gone to see them. They had them go into the studio. They evaluated the tapes when they came back and said, “We’ll sign the guitar player, but we want a different drummer and bass player.” It emanated from that. It was very much seen by Polydor as Rory with two other guys. And to a certain extent that’s how Rory saw it too.

How big did Taste seem to be getting by 1970?

They’d broken huge ground in Europe, in Scotland and in the north-east. But they were ignored by sections of the UK music press, who took the attitude of “How can you have a rock band from Ireland?” People made condescending remarks. But then they did the Isle of Wight Festival, playing on the Friday when everyone was just waiting to rock. A huge army of Taste fans had come over from France, Germany, Holland and Denmark. For a lot of those people, Taste were their band. They did five encores.

You saw Taste’s split from Rory’s point of view. Why had such a huge gap opened up between him and other two?

Management issues and financial issues played a huge part. The band were playing through the PA system that Rory had inherited from his showband days. They were travelling in a small Ford Transit with me as their road manager. There were four of us, and the back seat was a bench seat from an old Volkswagen propped up on a Marshall stack. They were making very good money, and yet they were living in bedsits in Earl’s Court. It was obvious they weren’t being managed correctly. So Rory went to the other two and said, “We need to get rid of the manager.” But the manager was from Northern Ireland, and so were the other two, and they sided with him. A split became inevitable.

Did Rory regret Taste’s break-up in later years?

Musically, he liked working with the other two – in fact, in the ’90s when he was forming a new lineup, he considered getting in touch with John – but the break-up caused a huge depression in him. He felt a huge opportunity had been passed by. He never performed Taste’s songs onstage again. Some nights you’d hear him break into the riff of one of them, and you could tell he’d be itching to play the whole song, and the audience would be dying to hear it, but he never did. I suppose he felt he’d lost ownership of that music.

INTERVIEWS: DAVID CAVANAGH

The History Of Rock – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – is now on sale in the UK. Click here for more details.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.