Great things come in crazy packages. Newly remastered albums, plus remastered ephemera... You can bake your tapes. You can preserve the oxides, futureproof your masters against all future music formats. But you’ll never improve on the authenticity of a group talking into a journalist’s tape recorder in 1976. Barely audible through the background noise (clanking coffee cups; rattling tube train carriages), on “Listen”, one of the early tracks collected here, the young Clash are interviewed by Tony Parsons, about whether they think they will succeed in “changing stuff”. Joe Strummer, (for all the logans on his shirts, a realist) is certain: “I don’t think we’ll ever have the power,” he says. “You just have to do what you can do.” Sound System (pitched as “the ultimate box set”) reminds us that one thing The Clash did succeed in changing was The Clash. Not a band shy of drawing an ideological line in the sand as far as music was concerned, whether that was “White Man In Hammersmith Palais” or “1977” (“No Elvis or Beatles or the Rolling Stones…”), The Clash still refused to be painted into a corner by punk. In a time when bands defined themselves by what they opposed, The Clash were about an embracing of possibilities. It was a policy that alienated as many people as it thrilled. If you were the kind of punk who couldn’t understand that a band from your subculture had given you the keys to a city filled with Zydeco, hip-hop, funk and dub, then you probably wouldn’t be the person to enjoy Sandinista – and indeed you were discouraged from buying it by the singer in the group. For all their military chic, The Clash didn’t want an army – they wanted free thinkers. Sound System poses the question of just how free-thinking a Clash fan is these days. Is there anything “punk” about a box set that collects the band’s first five albums and three discs of rarities into a box styled like a boombox stereo? Initial fan reaction would suggest not – not even when it includes repro fanzines, posters, stickers and Clash “dog tags”. As with the legacy material of Jimi Hendrix, Clash fans have a clear idea of want they rather than simply lapping up what they’re given. In the former list of demands are a live album from the band’s 1981 stand at Bond’s Casino in New York, and an issue of Rat Patrol From Fort Bragg, the moot double album from which Combat Rock was ultimately derived. Clash completists won’t be overwhelmed by Sound System. The “Extras” discs do contain interesting items: the band’s 1976 Beaconsfield Film School recordings with Julien Temple, and the Guy Stevens first album demos. Joe Strummer thought these left “White Riot” sounding “like Matt Monroe” because the producer insisted he pronounce the letter “t”. The accompanying DVD provides evocative film medleys of the early Clash from the collections of Temple and Don Letts. While these discs help with your Clash housekeeping, collecting B-sides and the scarce “Capital Radio” EP, actual unissued rarities are limited to the first two tracks of Rat Patrol: “The Beautiful People Are Ugly Too” and “Idle In Kangaroo Court” (formerly “Kill Time”). The unedited Straight To Hell and “Midnight To Stevens”, completists will already have from The Clash On Broadway. This, after all, is not a treasure trove – it is a handsome box with a poster tube shaped like a cigarette. Still, that paucity of extras obliquely provides more evidence for the band’s spontaneous creativity – there wasn’t a lot “spare”. As we know, “Train In Vain” was delivered too late for a sleeve credit on London Calling, and much of Sandinista was written in the studio. Even after their demise, The Clash were driven by spontaneity not strategy: as recently as 2010 a long-moot 30th anniversary reissue of Sandinista simply failed to materialize. The mood, we imagine, just wasn’t right. Instead, it and its partner albums are collected here in book style sleeves (a bit more recording detail wouldn’t have hurt), in remastering by Tim Young that is crisp, punchy and detailed. The debut benefits enormously from the enterprise, revealing anew how Mick Jones’s Mott-like lead lines served to elevate the group’s playing. Hearing Cut The Crap as an enormously loud military epic helps rehabilitate it somewhat, even if it can’t work miracles on what is basically three strong opening songs. The true breakthrough, London Calling could retain a thrilling room sound played down the line from a red phone box, and inevitably does so here. With their last two albums, as we know, the band attempted (not always successfully) to create empathetic music, without boundaries. With songs like “Magnificent Seven” and “Rebel Waltz” or “Straight To Hell” we’re hearing just how successfully The Clash had enacted a revolution on themselves – from a hardline, to music that was without orthoxy or dogma of any kind. So maybe the path to this point hadn’t actively changed stuff. The Clash had done what they could do – now society needed to follow their example. John Robinson

Great things come in crazy packages. Newly remastered albums, plus remastered ephemera…

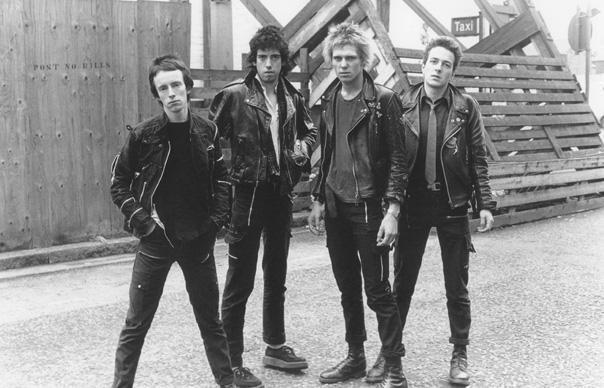

You can bake your tapes. You can preserve the oxides, futureproof your masters against all future music formats. But you’ll never improve on the authenticity of a group talking into a journalist’s tape recorder in 1976. Barely audible through the background noise (clanking coffee cups; rattling tube train carriages), on “Listen”, one of the early tracks collected here, the young Clash are interviewed by Tony Parsons, about whether they think they will succeed in “changing stuff”. Joe Strummer, (for all the logans on his shirts, a realist) is certain: “I don’t think we’ll ever have the power,” he says. “You just have to do what you can do.”

Sound System (pitched as “the ultimate box set”) reminds us that one thing The Clash did succeed in changing was The Clash. Not a band shy of drawing an ideological line in the sand as far as music was concerned, whether that was “White Man In Hammersmith Palais” or “1977” (“No Elvis or Beatles or the Rolling Stones…”), The Clash still refused to be painted into a corner by punk. In a time when bands defined themselves by what they opposed, The Clash were about an embracing of possibilities.

It was a policy that alienated as many people as it thrilled. If you were the kind of punk who couldn’t understand that a band from your subculture had given you the keys to a city filled with Zydeco, hip-hop, funk and dub, then you probably wouldn’t be the person to enjoy Sandinista – and indeed you were discouraged from buying it by the singer in the group. For all their military chic, The Clash didn’t want an army – they wanted free thinkers.

Sound System poses the question of just how free-thinking a Clash fan is these days. Is there anything “punk” about a box set that collects the band’s first five albums and three discs of rarities into a box styled like a boombox stereo? Initial fan reaction would suggest not – not even when it includes repro fanzines, posters, stickers and Clash “dog tags”. As with the legacy material of Jimi Hendrix, Clash fans have a clear idea of want they rather than simply lapping up what they’re given. In the former list of demands are a live album from the band’s 1981 stand at Bond’s Casino in New York, and an issue of Rat Patrol From Fort Bragg, the moot double album from which Combat Rock was ultimately derived.

Clash completists won’t be overwhelmed by Sound System. The “Extras” discs do contain interesting items: the band’s 1976 Beaconsfield Film School recordings with Julien Temple, and the Guy Stevens first album demos. Joe Strummer thought these left “White Riot” sounding “like Matt Monroe” because the producer insisted he pronounce the letter “t”. The accompanying DVD provides evocative film medleys of the early Clash from the collections of Temple and Don Letts.

While these discs help with your Clash housekeeping, collecting B-sides and the scarce “Capital Radio” EP, actual unissued rarities are limited to the first two tracks of Rat Patrol: “The Beautiful People Are Ugly Too” and “Idle In Kangaroo Court” (formerly “Kill Time”). The unedited Straight To Hell and “Midnight To Stevens”, completists will already have from The Clash On Broadway.

This, after all, is not a treasure trove – it is a handsome box with a poster tube shaped like a cigarette. Still, that paucity of extras obliquely provides more evidence for the band’s spontaneous creativity – there wasn’t a lot “spare”. As we know, “Train In Vain” was delivered too late for a sleeve credit on London Calling, and much of Sandinista was written in the studio. Even after their demise, The Clash were driven by spontaneity not strategy: as recently as 2010 a long-moot 30th anniversary reissue of Sandinista simply failed to materialize. The mood, we imagine, just wasn’t right.

Instead, it and its partner albums are collected here in book style sleeves (a bit more recording detail wouldn’t have hurt), in remastering by Tim Young that is crisp, punchy and detailed. The debut benefits enormously from the enterprise, revealing anew how Mick Jones’s Mott-like lead lines served to elevate the group’s playing. Hearing Cut The Crap as an enormously loud military epic helps rehabilitate it somewhat, even if it can’t work miracles on what is basically three strong opening songs.

The true breakthrough, London Calling could retain a thrilling room sound played down the line from a red phone box, and inevitably does so here. With their last two albums, as we know, the band attempted (not always successfully) to create empathetic music, without boundaries. With songs like “Magnificent Seven” and “Rebel Waltz” or “Straight To Hell” we’re hearing just how successfully The Clash had enacted a revolution on themselves – from a hardline, to music that was without orthoxy or dogma of any kind.

So maybe the path to this point hadn’t actively changed stuff. The Clash had done what they could do – now society needed to follow their example.

John Robinson