Morrison and co's oblique tour documentary... Not only was he singer, poet and lizard king, Jim Morrison was also a decent movie critic. Asked about the filming that ultimately ends up as A Feast Of Friends, he looks characteristically bemused but makes a wry observation. “It’s a fictional documentary,” he tells the camera. “It’s making itself…” He’s certainly on to something. Neither as tedious as a procedural rock doc, nor as abstract as a piece of period freaksploitation, A Feast For Friends – like most Doors-related film artifacts – occupies a place between home movie and next-level music piece, effortlessly over-reaching one role but falling short of the other. Filmed by Paul Ferrara, a UCLA Film School friend of Morrison’s, A Feast Of Friends doesn’t have much in the way of narrative, but it makes up for it in sheer beauty, a powerful Doors quality. Notionally an account of the band’s 1968 American tour, in truth that fact is more something that you discover for yourself than from the film. Faced with a wealth of good material, deriving from the madness and controversy of Doors performances at the time, Ferrara seems uncertain what to do. Undoubtedly a talented film-maker and editor, he montages stage invasions to the extent that a disproportionately large chunk of the film’s running time is spent watching a Keystone Cops slapstick of kids foiled by burly, nightstick-wielding policemen. Nor is any of this accompanied by live music. Better by far are the moments when he lets the film run, and observe the Doors being a great live band. No-one over the age of 19 is probably especially excited about hearing “The End” another time, but the long preamble here, where Morrison attempts to get the lights turned down in the auditorium raises warm laughter, as might greet an accomplished chat show guest, and casts Morrison in a different light. As much as by their music, the Doors worked by seduction, and a strength of his film is that Ferrara allows himself to be seduced. Never mind what they think their movie is about – there’s a great deal of pleasure to watch The Doors simply walking about in the modern America that charmed and horrified them. There is a beautiful vignette of the band on a yacht, and some nice stuff from a small plane. Watching the band on a scenic monorail, rubbing shoulders, just about, with John Q Public in his sports coat, is just wonderful – the band’s potential to charm and outrage right there in the carriage. The band and their public, specifically the fragile boundaries between them is the film’s tacit subject. The stage invasions are one thing, but what is almost accidentally recounted here is the band’s growing stature, and the elevation of Jim Morrison into a star – and about the contexts in which this has meaning, and those where it doesn’t. We follow the band silently cross a carpeted expanse en route to the stage, a mass of press and “industry” others behind a cordon. We are in the limousine as the band arrive at a venue: fans address Morrison, and one girl places her hand on his crotch, more to her disbelief than his. We are backstage with a girl who has been hit by a chair. She is sitting with Morrison, who explains to the camera what has happened, and wipes the blood that is streaming down her face. The moments are both incredibly intimate, of course. But what’s staggering about them is not so much the sense of a boundary being crossed, as a boundary simply not being there in the first place. You can’t imagine Mick Jagger wiping blood in ’72, or - as Morrison does here – having a conversation with an intense, pipe-chewing clergyman about the nature of his art. Later in 1968, the Doors entered a more dangerous arena – the British living room, in the run-up to Christmas. The first rock film to be commissioned by UK TV, The Doors Are Open (the supporting feature on this DVD) is a black and white film which captures the band in London, backstage, and on it at the Roundhouse just a few days after their US tour ended. The narrator advises that to his fans Jim Morrison is “poet, prophet and politician.” Where Ferrara’s camera has no agenda, The Doors Are Open has one set in stone: the Doors as a political band, and duly intercuts their music with footage of news events. Jim Morrison, to his credit, comes up with some mildly controversial supporting quotage (“These days to be a superstar you have to be a politician or an assassin”), but it is Robby Krieger who best articulates the band and the mood of this DVD as a whole. Is the band political? “Our music,” he says, “is more symbolic.” EXTRAS: Extra scenes: Morrison swimming, communing with rocks etc. 7/10 JOHN ROBINSON

Morrison and co’s oblique tour documentary…

Not only was he singer, poet and lizard king, Jim Morrison was also a decent movie critic. Asked about the filming that ultimately ends up as A Feast Of Friends, he looks characteristically bemused but makes a wry observation. “It’s a fictional documentary,” he tells the camera. “It’s making itself…”

He’s certainly on to something. Neither as tedious as a procedural rock doc, nor as abstract as a piece of period freaksploitation, A Feast For Friends – like most Doors-related film artifacts – occupies a place between home movie and next-level music piece, effortlessly over-reaching one role but falling short of the other.

Filmed by Paul Ferrara, a UCLA Film School friend of Morrison’s, A Feast Of Friends doesn’t have much in the way of narrative, but it makes up for it in sheer beauty, a powerful Doors quality. Notionally an account of the band’s 1968 American tour, in truth that fact is more something that you discover for yourself than from the film.

Faced with a wealth of good material, deriving from the madness and controversy of Doors performances at the time, Ferrara seems uncertain what to do. Undoubtedly a talented film-maker and editor, he montages stage invasions to the extent that a disproportionately large chunk of the film’s running time is spent watching a Keystone Cops slapstick of kids foiled by burly, nightstick-wielding policemen. Nor is any of this accompanied by live music.

Better by far are the moments when he lets the film run, and observe the Doors being a great live band. No-one over the age of 19 is probably especially excited about hearing “The End” another time, but the long preamble here, where Morrison attempts to get the lights turned down in the auditorium raises warm laughter, as might greet an accomplished chat show guest, and casts Morrison in a different light.

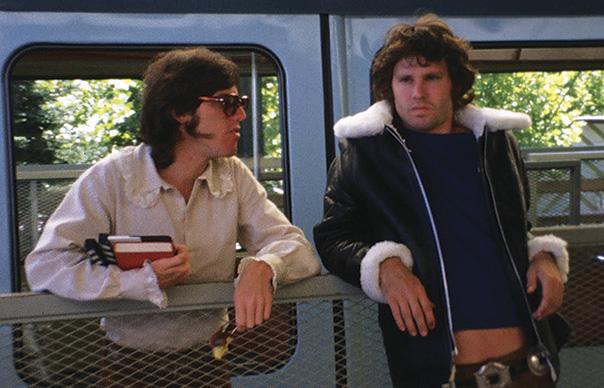

As much as by their music, the Doors worked by seduction, and a strength of his film is that Ferrara allows himself to be seduced. Never mind what they think their movie is about – there’s a great deal of pleasure to watch The Doors simply walking about in the modern America that charmed and horrified them. There is a beautiful vignette of the band on a yacht, and some nice stuff from a small plane. Watching the band on a scenic monorail, rubbing shoulders, just about, with John Q Public in his sports coat, is just wonderful – the band’s potential to charm and outrage right there in the carriage.

The band and their public, specifically the fragile boundaries between them is the film’s tacit subject. The stage invasions are one thing, but what is almost accidentally recounted here is the band’s growing stature, and the elevation of Jim Morrison into a star – and about the contexts in which this has meaning, and those where it doesn’t.

We follow the band silently cross a carpeted expanse en route to the stage, a mass of press and “industry” others behind a cordon. We are in the limousine as the band arrive at a venue: fans address Morrison, and one girl places her hand on his crotch, more to her disbelief than his. We are backstage with a girl who has been hit by a chair. She is sitting with Morrison, who explains to the camera what has happened, and wipes the blood that is streaming down her face. The moments are both incredibly intimate, of course. But what’s staggering about them is not so much the sense of a boundary being crossed, as a boundary simply not being there in the first place. You can’t imagine Mick Jagger wiping blood in ’72, or – as Morrison does here – having a conversation with an intense, pipe-chewing clergyman about the nature of his art.

Later in 1968, the Doors entered a more dangerous arena – the British living room, in the run-up to Christmas. The first rock film to be commissioned by UK TV, The Doors Are Open (the supporting feature on this DVD) is a black and white film which captures the band in London, backstage, and on it at the Roundhouse just a few days after their US tour ended. The narrator advises that to his fans Jim Morrison is “poet, prophet and politician.”

Where Ferrara’s camera has no agenda, The Doors Are Open has one set in stone: the Doors as a political band, and duly intercuts their music with footage of news events. Jim Morrison, to his credit, comes up with some mildly controversial supporting quotage (“These days to be a superstar you have to be a politician or an assassin”), but it is Robby Krieger who best articulates the band and the mood of this DVD as a whole. Is the band political? “Our music,” he says, “is more symbolic.”

EXTRAS: Extra scenes: Morrison swimming, communing with rocks etc. 7/10

JOHN ROBINSON