From the beginning the Kinks’ career was intimately entwined with the BBC. In the year following the August 1964 success of “You Really Got Me” the band were called in to record eight radio sessions, broadcast to the nation and around the world. When the BBC commissioned Ray Davies to write topical tunes for shows like The 11th Hour and Where Was Spring?, we got the first inkling of the Kinks’ future direction, somewhere between Dennis Potter and Lionel Bart. And it was the BBC’s banning of “Plastic Man” in 1969 (for the seditious use of the word “bum”) that was a crucial nail in the Kinks’ late 60s commercial coffin. The Kinks’ experience seems to exemplify the full Reithian spectrum of imperial arrogance, byzantine bureaucracy but, nevertheless, astonishing cultural benevolence. So it’s somehow fitting that the extensive, exhaustive Kinks reissue campaign of the last couple of years comes to a conclusion with this five-disc plus DVD trawl of the BBC archive. Essentially this new box is an expansion of the 2001 Kinks BBC Sessions 1964-1977, now incorporating more thorough selections from the early mid-60s sessions, the full live sets from Golders Green Hippodrome 1974 and Finsbury Park 1977, a handful of mid-90s Radio 1 appearances, plus a few performances that were wiped from the BBC archives but have been recovered from fan recordings. In a way, tracking the the five appearances here of “You Really Got Me” included here adds up to one of the most succinct biographies of the band. In the context of the spindly RnB and north London Merseybeat of the early sessions, the first appearance of the song, recorded at the Playhouse Theatre in September 1964, is still astonishing. By 1974, for the Hippodrome show, the song has been turbocharged for the Zeppelin era. By 1977 it’s the tired and emotional singalong finale to what was already in danger of becoming a nostalgia show. And, performed on the Emma Freud Radio 1 show in 1994, the final song of the collection, it’s part of a set that is already primed for the band’s BritPop revival. But it’s not clear that much of the new material adds a great deal to original two-disc package. From the early sets we now have further evidence of the Kinks’ not always convincing early RnB incarnation - including ragged takes on Chuck Berry’s “Little Queenie” and JD Miller’s “I’m A Lover Not A Fighter” (both available, like a lot of the material assembled here, on extra discs on last year’s deluxe editions). Elsewhere things paradoxically have been lost. “Did You See His Name?”, a wry commentary on a life of petty thievery and newspaper notoriety, was one of the songs Davies wrote for the satirical revue show The 11th Hour (where it was sung by Jeannie Lamb). This has now inexplicably vanished from the tracklist. In its place we get “Where Did My Spring Go?”, another relatively obscure slice of blackly comic exasperation, originally commissioned by Ned Sherrin for his tv revue Where Was Spring? (though again, previously available on the bonus disc of deluxe Village Green edition from 2004). Kinks kompletists will be intrigued to hear the handful of tracks previously thought lost, wiped from the archive before their value was realised, in particular the July 68 appearance on Colour Me Pop, the short-lived BBC2 spin-off from Late Night Line-Up. Disappointingly, the audio here is dismal, and apart from a brief rave up medley of “Dedicated Follower”/”Well Respected Man”/”Death of a Clown”, the other tracks are seemingly indistinguishable from the recorded versions. Surprisingly there is no appearance for the 1969 sessions from the Once More With Felix show which recently came to light on youtube. Nevertheless, for all its omissions and repetitions, the sheer scale of this archive still feels like an exemplary work of preservation. For the stilted interviews, from Brian Matthew through to Johnnie Walker, the fluffed introductions by Alan Freeman and Bob Harris, the electrifying early sessions, the beautifully eccentric later flowering, these discs present the sensibility of band and broadcaster chiming in charmingly wonky harmony. Indeed, these days, as one of the last beleagured British institutions standing in the age of austerity, you would think the BBC is surely a fitting subject for a concept album, or at least a wistful protest song, in Ray Davies’ ongoing Muswell Hill ring cycle. Stephen Troussé Q+A Ray Davies What are your abiding memories of those early BBC sessions? No abiding memories of the BBC other than the fact it was like being at school. All the engineers were like scientists, and that rigid atmosphere helped us in many respects, because it made us feel more anarchic. Working at the BBC helped us to be more rebellious. Did being on the BBC feel like a vindication? Did it impress your family? Vindication? We qualified as human beings by being accepted at the BBC. In fact we failed the BBC audition. Everybody had to take one, we are still waiting for the confirmation we actually passed to be on the BBC, daily, by the post box. But nothing has arrived yet. Do the sessions give a better sense of the Kinks as a band than the studio records? Because these sessions were done very quickly, in and out, inbetween doing concerts, we never had time to refine them. It gives a good sense of the roughness of the band. Most of these recordings are unpolished, which for people who enjoyed the band live gave it the energy you usually didn’t get on the studio recordings which tended to be more refined After all the deluxe editions and this new box, is there much more in the Kinks archive left to release? Ironically this is just the tip of the iceberg, we just haven’t had the time to go through the vaults. There is an amazing archive out there of cassette demos to multitrack recordings. I look forward to doing it but it is a lifetime's work. INTERVIEW: STEPHEN TROUSSE

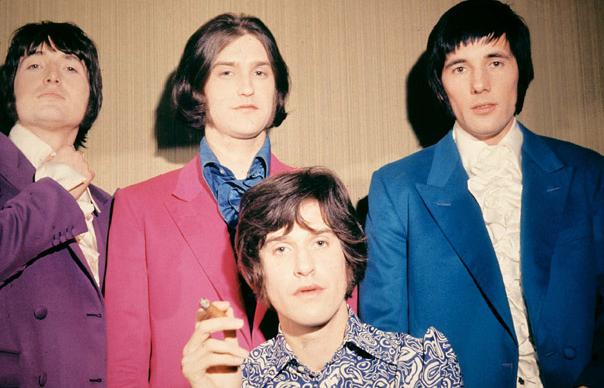

From the beginning the Kinks’ career was intimately entwined with the BBC. In the year following the August 1964 success of “You Really Got Me” the band were called in to record eight radio sessions, broadcast to the nation and around the world. When the BBC commissioned Ray Davies to write topical tunes for shows like The 11th Hour and Where Was Spring?, we got the first inkling of the Kinks’ future direction, somewhere between Dennis Potter and Lionel Bart. And it was the BBC’s banning of “Plastic Man” in 1969 (for the seditious use of the word “bum”) that was a crucial nail in the Kinks’ late 60s commercial coffin. The Kinks’ experience seems to exemplify the full Reithian spectrum of imperial arrogance, byzantine bureaucracy but, nevertheless, astonishing cultural benevolence.

So it’s somehow fitting that the extensive, exhaustive Kinks reissue campaign of the last couple of years comes to a conclusion with this five-disc plus DVD trawl of the BBC archive. Essentially this new box is an expansion of the 2001 Kinks BBC Sessions 1964-1977, now incorporating more thorough selections from the early mid-60s sessions, the full live sets from Golders Green Hippodrome 1974 and Finsbury Park 1977, a handful of mid-90s Radio 1 appearances, plus a few performances that were wiped from the BBC archives but have been recovered from fan recordings.

In a way, tracking the the five appearances here of “You Really Got Me” included here adds up to one of the most succinct biographies of the band. In the context of the spindly RnB and north London Merseybeat of the early sessions, the first appearance of the song, recorded at the Playhouse Theatre in September 1964, is still astonishing. By 1974, for the Hippodrome show, the song has been turbocharged for the Zeppelin era. By 1977 it’s the tired and emotional singalong finale to what was already in danger of becoming a nostalgia show. And, performed on the Emma Freud Radio 1 show in 1994, the final song of the collection, it’s part of a set that is already primed for the band’s BritPop revival.

But it’s not clear that much of the new material adds a great deal to original two-disc package. From the early sets we now have further evidence of the Kinks’ not always convincing early RnB incarnation – including ragged takes on Chuck Berry’s “Little Queenie” and JD Miller’s “I’m A Lover Not A Fighter” (both available, like a lot of the material assembled here, on extra discs on last year’s deluxe editions).

Elsewhere things paradoxically have been lost. “Did You See His Name?”, a wry commentary on a life of petty thievery and newspaper notoriety, was one of the songs Davies wrote for the satirical revue show The 11th Hour (where it was sung by Jeannie Lamb). This has now inexplicably vanished from the tracklist. In its place we get “Where Did My Spring Go?”, another relatively obscure slice of blackly comic exasperation, originally commissioned by Ned Sherrin for his tv revue Where Was Spring? (though again, previously available on the bonus disc of deluxe Village Green edition from 2004).

Kinks kompletists will be intrigued to hear the handful of tracks previously thought lost, wiped from the archive before their value was realised, in particular the July 68 appearance on Colour Me Pop, the short-lived BBC2 spin-off from Late Night Line-Up. Disappointingly, the audio here is dismal, and apart from a brief rave up medley of “Dedicated Follower”/”Well Respected Man”/”Death of a Clown”, the other tracks are seemingly indistinguishable from the recorded versions. Surprisingly there is no appearance for the 1969 sessions from the Once More With Felix show which recently came to light on youtube.

Nevertheless, for all its omissions and repetitions, the sheer scale of this archive still feels like an exemplary work of preservation. For the stilted interviews, from Brian Matthew through to Johnnie Walker, the fluffed introductions by Alan Freeman and Bob Harris, the electrifying early sessions, the beautifully eccentric later flowering, these discs present the sensibility of band and broadcaster chiming in charmingly wonky harmony. Indeed, these days, as one of the last beleagured British institutions standing in the age of austerity, you would think the BBC is surely a fitting subject for a concept album, or at least a wistful protest song, in Ray Davies’ ongoing Muswell Hill ring cycle.

Stephen Troussé

Q+A

Ray Davies

What are your abiding memories of those early BBC sessions?

No abiding memories of the BBC other than the fact it was like being at school. All the engineers were like scientists, and that rigid atmosphere helped us in many respects, because it made us feel more anarchic. Working at the BBC helped us to be more rebellious.

Did being on the BBC feel like a vindication? Did it impress your family?

Vindication? We qualified as human beings by being accepted at the BBC. In fact we failed the BBC audition. Everybody had to take one, we are still waiting for the confirmation we actually passed to be on the BBC, daily, by the post box. But nothing has arrived yet.

Do the sessions give a better sense of the Kinks as a band than the studio records?

Because these sessions were done very quickly, in and out, inbetween doing concerts, we never had time to refine them. It gives a good sense of the roughness of the band. Most of these recordings are unpolished, which for people who enjoyed the band live gave it the energy you usually didn’t get on the studio recordings which tended to be more refined

After all the deluxe editions and this new box, is there much more in the Kinks archive left to release?

Ironically this is just the tip of the iceberg, we just haven’t had the time to go through the vaults. There is an amazing archive out there of cassette demos to multitrack recordings. I look forward to doing it but it is a lifetime’s work.

INTERVIEW: STEPHEN TROUSSE